By Robert R. Thomas

In the January 2016 issue of EVM, I wrote a book review of Demolition Means Progress (2015) by Andrew Highsmith, a definitive account of the reality of Flint’s last 80 years. The book arrived in my life at a time when I desperately needed to understand the Flint I had returned to in 2005.

Eleven years later life in Flint has come to a new bend in the river where I needed to reflect and review. Where had we come since Highsmith’s scholarly enlightenments? Where might we be headed?

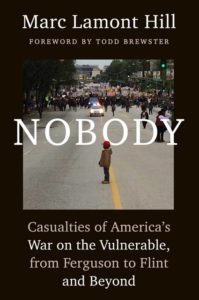

Along comes Marc Lamont Hill’s NOBODY: Casualties of America’s War on the Vulnerable, from Ferguson to Flint and Beyond (2016) to fill lots of voids for me.

Along comes Marc Lamont Hill’s NOBODY: Casualties of America’s War on the Vulnerable, from Ferguson to Flint and Beyond (2016) to fill lots of voids for me.

Hill is a renowned American intellectual and journalist. His reporting from the grounds of Ferguson and Flint is solidly supported by his meticulous scholarly research as exhibited in the book’s fifty pages of notated documentation.

His preface states: “This is a book about what it means to be Nobody in twenty-first-century America.” He then defines the term:

“To be Nobody is to be vulnerable.

To be Nobody is to be subject to State violence

To be Nobody is to also confront systemic forms of State violence.

To be Nobody is to be abandoned by the State.

To be Nobody is to be considered disposable.”

The preface concludes with the book’s premise to tell the stories of those marked as Nobodies, spotlight their humanity, and inspire principled action. To do so, Hill fires off a series of LED flashes in the form of seven one-word chapter headings to illuminate his stated goals.

“Nobody,” the first chapter of Hill’s analysis of the casualties of America’s war on the vulnerable, examines what happened in Ferguson to Michael Brown. The line story is well known, but Hill provides an illuminating back story including a racial history of East St. Louis, Illinois and St. Louis and Ferguson, Missouri and their interconnectedness. As Hill writes, “the discourse of race is at once indispensable and insufficient when telling the story of Ferguson and other sites of State-sanctioned violence against Black bodies.”

[In the interest of clarity and formatting consistency I have honored the author’s style in capitalizing both Black and White to denote equally the racial aspect of both groups. All people have racial components.]

While I found this back story revealing, the most chilling illumination of the chapter for me was the grand jury testimony of Darren Wilson, the White policeman who shot and killed Michael Brown.

“‘As he is coming towards me, I…keep telling him to get on the ground,’ the sandy-haired Wilson told the grand jury, using phrases that made him sound like he was a game hunter confronting a wildebeest: ’He doesn’t. I shoot a series of shots. I don’t know how many I shot, I just know I shot it.’”

Darren Wilson had executed “it.” Nobody.

“Broken,” Chapter Two, tells the stories of the police chokehold killing of Eric Garner on Staten Island for selling “loosies,” single cigarettes; Walter Scott, executed by police officer Michael Slager in North Charleston, SC, who pulled Scott over for having a broken “third taillight” and recorded by a cell-phone video; and Sandra Bland’s hanging in a Texas jail, the end result of being pulled over by a Texas state trooper named Brian Encinia for changing lanes without signaling and then arresting her for talking back to him.

While there are remaining questions about the circumstances of their deaths, there is no doubt that all three “ultimately died because of a series of unnecessary actions by the State,” Hill writes. These Nobodies were broken by State power, Hill asserts.

“Bargained” centers on the aftermath of Freddy Gray’s death while in the custody of the Baltimore Police Department and the judicial failures of the plea-bargaining process which, in effect, has given more power to prosecutors than to judges. How this has come to be is the meat of this chapter which concludes, “nothing has been done to repair a system that prosecutes, judges, and sentences millions of vulnerable citizens with the stroke of a single pen–and without any semblance of justice.”

“Armed” opens with Michael Dunn’s “Stand Your Ground” defense for assassinating unarmed 17-year-old Jordan Davis for playing “that thug music” too loudly in a convenience store parking lot and defying Dunn’s request that they turn the volume down. The verbal confrontation with the teens, one of whom was Davis, ended with Dunn, a White software developer, pulling a pistol from his glovebox and firing ten shots at the adjacent vehicle of unarmed Black teens playing rap music.

There follows an examination of the confluence of “Stand Your Ground,” the NRA and the U.S. Supreme Court in 2008 who dumbed down the Second Amendment from “well regulated militia” to any Tom, Dick, or Harriet who can obtain a firearm. It’s Dodge City all over again in America by law.

“If extrajudicial dispute resolution has been sanctioned on our streets, it has a counterpart on the other side of the spectrum in the gross militarization of our police,” writes Hill. “Even as we have handed some of the responsibility for policing over to the ‘Armed Citizen,’ we have been turning the police themselves into a small-scale army.”

He then cites Washington Post journalist Radley Balko who describes this militaristic trend in police forces as a development in three stages: response to the Black Power movement and the race riots of the 1960s, prompting a War on Crime; the War on Drugs; and the War on Terror after 9/11. The “war” meme plays big here because, writes Hill, “The police, after all, can fight crime, but you need an army to fight a war.” He adds, “Using the language of war to attack a social problem worked to distort the image of those who suffered, just as propaganda in real wartime serves to distort the image of the enemy into a subhuman monstrosity.”

When you wage a war on neighborhoods and treat citizen homes like occupied territory, collateral damage occurs, Nobodies die, as Hill illustrates with the mistaken assassination by police of 92-year-old Kathryn Johnston in the Bluff neighborhood of Atlanta where she had resided for seventeen years, the victim of a misguided unlimited no-knock warrant by police. “Meanwhile,” Hill concludes, “the State-sanctioned war on citizens, guilty and innocent, continues.”

“Caged” highlights the criminal justice system’s mass incarceration of America’s disposable populations, most of whom are people of color, the poor, the vulnerable.For Hill the story begins with Nelson Rockefeller’s War on Drugs, mandatory sentencing and the State-sanctioned violence of Attica prison in which more Nobodies died at the hands of State power. Like his short tour of the history of the American prison, his history of Attica prison is very enlightening, and another example of the author’s scholarly research.

“But the issue of prison privatization is a symptom of a much larger illness,” writes Hill. “Whether prisons are publicly or privately administered, mass incarceration itself is largely indebted to an over-arching ‘prison-industrial complex,’ which can be defined as the ‘over-lapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social, and political problems.”

“Emergency” opens with Flint’s immiseration and the poisoning of its public water supply at the hands of State power based on profits over people. Hill’s focus on Flint and other post-industrial American cities in similar straits examines the economic system under which we all live. Paralleling the current economy with the Gilded Age of America and the era of the Robber Barons, Hill sites historian T.J. Jackson Lears’ remark that the disparities of the Gilded Age were the product of a “galloping conscienceless capitalism,” which Hill says is an apt “description of our own day.”

Hill ends NOBODY with the “Somebody” chapter that concludes:

“At every moment in history, oppression has been met with resistance. In every instance in which the State has consigned the vulnerable to the status of Nobody, The People have asserted that they are, in fact, Somebody. In doing so, they offer hope that another world is indeed possible, that empires eventually fall, and that freedom is closer than we think.”

EVM staff writer and columnist Robert R. Thomas can be reached at captzero@sbcglobal.net.

You must be logged in to post a comment.