Flint Water Advisory Task Force Final Report, presented to Gov. Rick Snyder, March 21, 2016

Recommendation #7 to the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services , p. 10:

“Establish and maintain a Flint Toxic Exposure Registry to include all the children and adults residing in Flint from April 2014 to present.”

By Teddy Robertson

In a significant marker of forward momentum in the aftermath of the water crisis, that 2016 recommendation has become a reality.

“It’s an enormous project,” says Dr. Nicole Jones, project director for the Flint Registry. It’s a phrase that repeats several times in an hour-long conversation.

The Flint Registry is a four-year, federally-funded voluntary data collection effort designed to monitor the health of the Flint community, link residents to resources available to them now, and advocate for future resources that will be needed in decades to come.

Funding originated with $14.4 million earmarked for Flint from the $150 million Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation (WIIN) Act signed by President Obama in December 2016. Dollars come in annual awards ($3.2 million this year) through the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and related Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registries. The Registry target population is anyone exposed to the Flint water crisis (including prenatal exposure) from April 2014 to Oct. 2015—the high-risk period prior to the emergency declaration announcement.

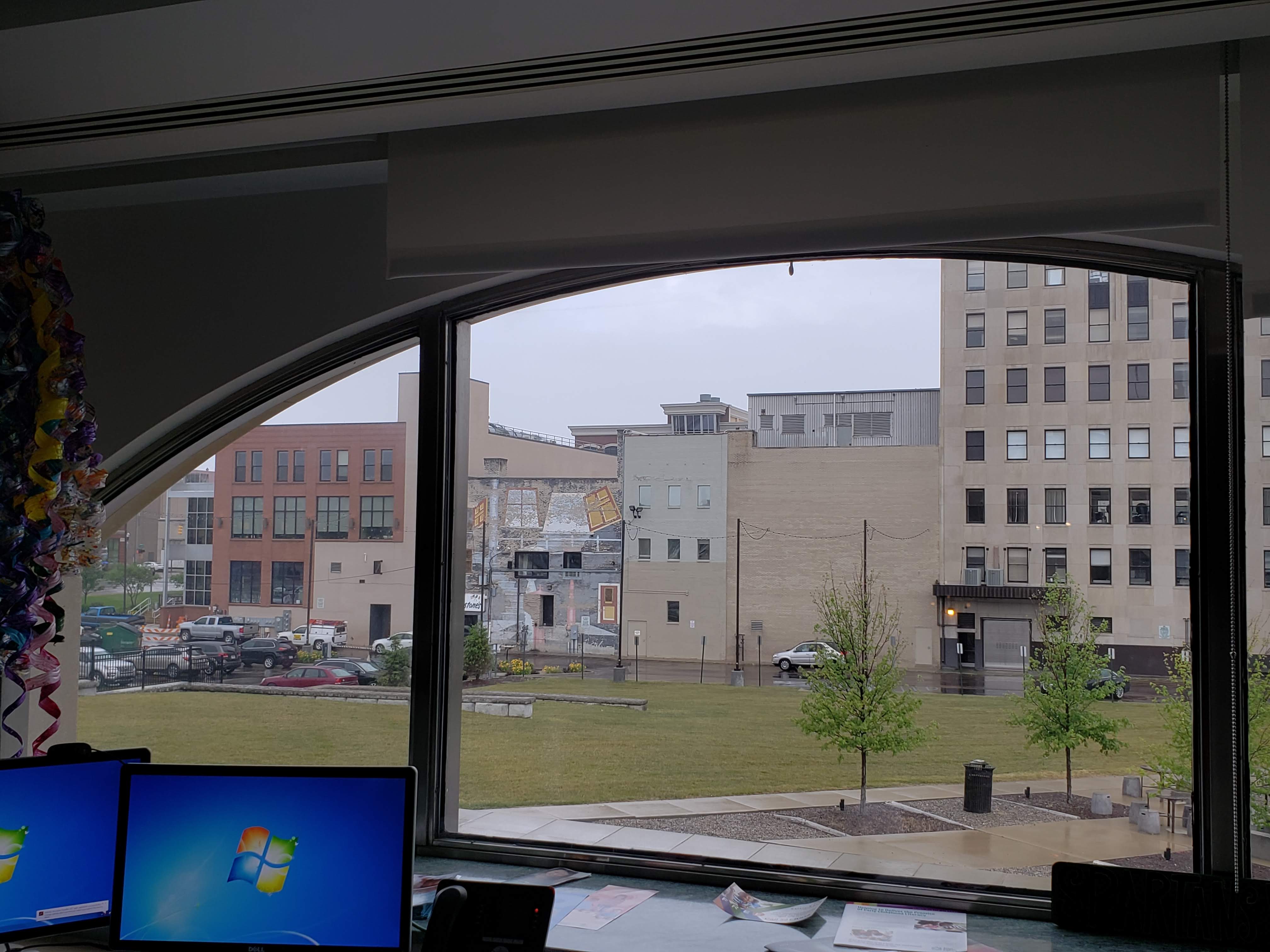

Architectural artifacts of the old Flint Journal building highlight the Flint Registry offices downtown (Photo by Flint Registry)

Tucked into the second floor of the old Flint Journal building, now the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine, the Flint Registry staff works in a space that once housed newspaper offices. As we walk through the newly converted area, light enters the remodeled area through lunette windows, a legacy of Detroit-architect Albert Kahn’s classy 1924 design. White work surfaces gleam against the old industrial flooring. It is a quiet Friday in late June and the Registry’s official launch in September is two months away.

A Genesee County native, Jones is an MSU-trained epidemiologist who has worked in perinatal and maternal health and has been a member of epidemiologic research teams since 1996. She spent six years at MSU’s Biomedical Research Informatics Core working in data systems and customized data management. She joined the Registry staff as director in March 2017.

Dr. Nicole Jones (Photo courtesy of College of Human Medicine)

If the term “registry” seems new, think 9/11 and the World Trade Center. In the aftermath of the largest disaster in U.S. history, a voluntary health registry was established to track health impacts and the effects of contamination. The World Trade Center Health Registry serves as one of several external advisors to the Flint Registry. Earlier post-disaster registries followed the 1979 Three Mile Island nuclear accident and the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. Closer to home, a registry was set up in Michigan after the 1973 PBB disaster when cattle feed was contaminated with a flame retardant and tainted the Michigan beef and milk supply.[1]

How is the process proceeding?

“Until September when it goes live, we consider the Registry to be in its planning phase,” Jones explains. “We are just finishing up our first year—the first year of the grant is really getting ready to launch. Workgroups are constructing survey forms, estimating the total number of people at risk (or statistical denominator), as well as an enrollment goal, laying out marketing plans, finalizing consent processes, and conferring with external advisory resources like the World Trade Center Registry, lead expert Dr. Philip Londrigan, the NAACP Environmental Justice Program, and public health law experts.”

Flint residents’ input comes through a community advisory board (22 members), Parent Partners (17 persons, all backgrounds and all Flint wards), youth advisory groups, and nearly 40 outreach and engagement partner organizations. “In early community feedback people said they wanted to be able to pre-enroll before launch. The Registry planners responded and pre-enrollment was announced,” Jones explains. So far more than a thousand have pre-enrolled since the website opened in January.

“We know what people are concerned about through their pre-enrollment comments,” Jones says. “Skin rashes, data security, other health issues, more attention to seniors, video for those who cannot read, and pipe replacement. Through website feedback people asked about water bill assistance, lead testing for pets, help with Medicaid Expansion enrollment, and confidentiality.”

The planning period is intense, but Jones is calm. “Right now we are working to understand everything all in order to refer people, to have agencies on-boarded so that as people connect, their health care concerns are getting addressed,” she said.

Why is the Flint Registry unusual?

Unlike most registries which track disaster consequences for future research, the Flint Registry’s immediate goal is to link people with programs and resources. It is designed for support. Enrolling in the Flint Registry means connecting to Registry collaborators like the Greater Flint Health Coalition for referral to critical services: lead elimination in the home, nutrition guidance, finding a health care “home,” and monitoring child development and early education.

Information is held with the Registry and not shared without consent. A legal support team and three IT centers (Hurley Hospital’s EPIC patient portal, Great Lakes Health Connect for referrals, and MSU Informatics) enable the Registry ensure and protect data.Because the Registry database documents usage of educational, environmental and community services, it can encourage people to use the programs available now, before time-limited funding may expire. Long term, the Registry can guide decisions about what resources will be needed in the future.

Gleaming work surfaces ready for action in the Flint Registry quarters (Photo by Flint Registry)

“It all begins with a baseline health survey that screens adults and children (through their parents),” Jones explains. “Things we need to understand because our goal is to connect everyone with services they need. We will learn what resources enrollees are eligible for, and what they are using, put referral to other services in place, ‘onboard’ enrollees to the platform, check phone numbers for ongoing contact to confirm that referrals—to Valley Area Agency on Aging, the Genesee Health Plan, or the Greater Flint Health Coalition—have been successful, and find out how they are doing.”

Addressing inequity and vulnerability

Lack of basic services in a shrinking, disinvested city like Flint left residents highly vulnerable during the water crisis, Jones notes. The Registry focuses on four essential services: lead elimination, nutrition, health care access, child development and early education.

“We get at these through the baseline survey,” she says.

Lead elimination and health care access go to the heart of inequity and vulnerability. The survey asks about current potential lead exposure: is the home lead free? Even renters can get a full home inspection through the Children’s Health Coverage Program or CHIP.

A lead-free home means primary protection—before lead gets into the blood and it is too late. But CHIP is a time-limited program, so residents need to get connected to it now, Jones stresses.

Health care access means a “medical home.” “If people do not have a place where they and their children can go for health care,” she explains, “we use the Greater Flint Healthcare Coalition and its CHAP program.”

CHAP, the Children’s Healthcare Access Program, is a medical home model to improve health outcomes of low-income children covered by Medicaid. With CHAP as a medical home, people can link to community services, education, transportation, interpretation, nutrition, and counseling for complete medical care.

Roots of the Registry

The Flint Registry has deep roots in the water crisis chronology. In Jan. 2016, nearly two months before the Flint Water Advisory Task Force Final Report was presented to Governor Snyder on March 21, Hurley Children’s Hospital and MSU’s College of Human Medicine formed the Pediatric and Public Health Initiative.

The PPHI team envisioned a registry as part of its goal to “address the Flint community’s population-wide lead exposure and help all Flint children grow up healthy and strong.”

In Jan. 2017 a $500,000 grant from Michigan Department of Health and Human Services to the MSU College of Human Medicine allowed Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha as principal investigator and Jones as project director to lay the Registry groundwork. Together, they presented the Registry to the FACT Community Partners meeting under the dome at City Hall on Nov. 16, 2017.

Flint built, Flint strong

Flint Registry staff already hired and at work (from left) Tierre Cook-Howell, Ebony Stith, Alice Barnett (Photo courtesy of Flint Registry)

The Registry is committed to hiring in Flint. “Right now,” Jones says, “we foresee approximately 10 full- and part-time staff people this fall; job announcements just went out. We expect that enrollment will come in waves. We will learn for winter which areas need more staff. We know there are many barriers, so we use all modalities—online, by mail, by phone, and including persons coming in person to us here.”

The Registry’s Community Advisory Board reminds planners about need for translation assistance—ASL for the Deaf and hearing impaired, other languages, and help for the reading or vision-impaired, one-on-one or through a designated proxy. The Registry marketing team is filming commercials with ASL interpreters.

Jones also explained the relation between the Registry and Hurley-MSU Pediatric Public Health Initiative: “We at the Registry are part of the Hurley-MSU Pediatric Public Health Initiative, but have our own work groups: a team is building the survey and testing it with Parent Partners; a referral team ‘onboards’ other agencies to connect to services; a public health law team is working on multi-level consent protocols. We have our External Advisors like the World Trade Center Health Registry and lead expert, Dr. Londrigan, plus our local Youth Advisory Council and Community Advisory Board as well.”

And she says once more, “It’s an enormous project.”

Additional support for the Registry lies in what Jones calls “the synergies,” or the combined effect of other efforts. A program called “I RISE,” funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, up to 400 children 4.5 to 6 years of age will be assessed to see how lead impacts kids and to identify sources of resilience.

The April 2018 ACLU settlement with the State of Michigan, Flint Community Schools, and the GISD will provide $4.1 million fund to identify, and place on the Registry, school age youth from birth to age 25. Universal health screenings will take place across the county and enrollees can be referred to a Neurodevelopmental Center of Excellence to be established at Hurley Hospital and staffed by Genesee Health Systems.

Registry planners count on community synergies as local outreach partners, the nearly 40 different organizations that support the Registry, spread the word about enrollment. Volunteers from organizations like the Crim Foundation, the Flint Public Library, the YMCA, the Hamilton Community Health Network, Hispanic Technology Community Center, Flint Neighborhoods United and Flint churches will be invited to learn more about the Registry in training sessions and become trusted “Ambassadors” for enrollment.

The Registry signals a new chapter in the Flint water crisis, a chapter about recovery. Its motto—“Get Connected. Get Supported. Get Counted”—sums it up for Nicole Jones. The more people who enroll, the more powerful the Registry will be and, as Jones notes, “Congressional legislators are watching the Registry’s progress.”

Asked what is the biggest challenge facing the registry, Jones answered without hesitation, “To build trust in a traumatized community, while we support recovery.”

[1]Michigan PBB Research Registry after 1973 fire retardant chemical mixed into livestock feed; Research Registry enrolled more than 6,000 persons http://pbbregistry.emory.edu/Research/PBB_Clinicians_FactSheet_final_3_8_18.pdf

EVM contributing writer Teddy Robertson can be reached at teddyrob@umflint.edu.

You must be logged in to post a comment.