By Robert R. Thomas

Carlton Evans opened his presentation as the featured speaker for the recent Tendaji Talk at the Flint Public Library by posing two questions:

Carlton Evans opened his presentation as the featured speaker for the recent Tendaji Talk at the Flint Public Library by posing two questions:

How do we dismantle structural racism?

How do we eliminate white supremacy?

“The short answer is I don’t know,” he said to his questions. “The long answer is I have an opinion, but I don’t know if it’s gonna make a difference. I want to leave you with a call to action, but I am not sure if my call will inspire you to action. Yet it is action that we must take. People of color must take action. White people must take action.”

After a 35 years as a microbiologist, Evans changed careers to concentrate on social justice. He is currently a juvenile detention specialist at the Ingham County Youth Center. His presentation was titled “An Approach to Combatting Institutional and Cultural Racism.”

“I see a four-pronged approach,” said Evans. “White supremacy or oppression operates, according to Dr. Valerie Bass, on four levels. These are the four levels of oppression and change. The significance of the structure is that once you decide at what level the oppression is working on, then that’s the level you need to make the change on.” The four levels are personal, interpersonal, institutional and cultural.

“The personal level consists of the beliefs, conscious and unconscious, and your personal values.

“The interpersonal level, though, is highly interactive with other people being guided by these beliefs and values.

“The institutional level is the procedures, written and unwritten, that organizations might have.

“The cultural level is what we define as being good, beautiful and true.

The antidote for personal and interpersonal oppression, he added, is conversation, or rather directed dialogue such as the approach of the Tendaji Talks.

Tendaji Ganges

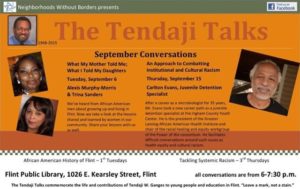

Honoring the life and social justice work of the late Tendaji Ganges, the Tendaji Talks, sponsored by Neighborhoods Without Borders, are conversations between audience and featured speakers centered on eliminating systemic racism.

While we as humans are making progress on the personal and interpersonal levels here in America, Evans said that “for lasting change to occur, there must be change on all four levels.”

The two levels Evans said he wished to focus on were the institutional and cultural levels. “Together they make up systemic, or structural racism,” he said. Systemic problems can only be fixed by systemic changes.

Regarding the institutional level of procedures, written and unwritten, Evans said, “We must mandate new rules and policies. To make new rules and policies, we must have power.

“White supremacy is not just going to to give up”

“Power is simply the ability to get what you need when you need it,” Evans asserted. “White supremacy is not just going to give up. Power never just gives up. It only surrenders to a greater power. Power is not given to you. We must build our own power. Power is built through relationships, and with those relationships, we build community. And that community needs to build a new political party, a party that is truly for the people and of the people. A party of all colors who believe that basic human and economic rights and racial and gender justice is not the unreasonable pie in the sky.

“Republicans do not care about social justice. Democrats do not care enough. They are two different names for the same system, a system of oppression.”

Evans then turned to the cultural level—the good, the beautiful, the true.

“We impact the cultural level by rendering justice,” he said. “And how do we achieve justice for crimes that have been committed over several centuries, even up to today?

“I think that one step is by admitting publicly, and in the highest centers of government that there was and is a crime being committed.

“And then a government commission does a national study looking at the effects of slavery, Jim Crow, the New Deal, red-lining and mass incarceration of people of color and of white folks. What did the nation gain from these activities? What did the nation lose?

“Is that bad?

“I have just described to you what reparations looks like.

“No amount of money can make up for this evil”

“Reparations isn’t about money. No amount of money can make up for this evil. Reparations is about truth, about justice.”

“Stories are very powerful. The stories we tell build our view of the world. We must tell new true stories. We must change the dominant story. The current dominant narrative in our country is that white is always right and that non-white is always wrong.

“We must make ourselves intentionally multi-racial.”

Evans concluded his presentation by saying that “Americans want simple solutions, yet complex problems demand complex solutions. A persistent problem demands a persistent and permanent solution. This is not about black versus white; this is about right versus wrong.”

The audience then joined Evans in a dialogue about what Evans described as “the matrix of oppression, classism, racism, power and money.”

A woman who introduced herself as Kimberly Pollock said that she would love to change our language and thereby change our perspectives.

“Let’s talk about systems and privilege,” she said, “instead of systems of oppression.” As an example, she offered: “When we to talk about race, we only focus on people of color and allow white people to forget that they are racial beings too. It seems to me that what we have been working to deracialize people of color. Well, if people of color make up 90% of the population of the world, wouldn’t it be more effective and efficient to racialize white people instead of deracializing people of color? Race is not something we are going to get rid of because it is so profitable. The problem is we mistake racism as a problem of hatred when racism is really a problem of power and profit.”

Evans pointed to a historian who said that the value of slaves in 1860 was more than all the the railroads in America, all the manufacturing, everything. “There were more millionaires in the Mississippi Valley than in all the rest of America,” said Evans. “So it’s about money; it’s always been about money.”

Privatization and mass incarceration

The current privatization of the mass incarceration of people of color was another example of a racist profit motive mentioned during this dialogue.

Evans restated that the purpose of racism is profit while hate is what justifies people doing it.

“We as human beings, that is our greatest talent” he said, “justifying our actions. Everybody can justify what they are doing. And a person likes to think of themselves as a good person. So you can’t treat a person bad unless you believe that that person is not a person.”

Another audience member spoke of the softness of the term social justice in institutional academia because, she said, “there is no evidence of it in the institution. And they don’t even see it as a problem.”

Evans responded by stating that “your definition of social justice has to name the evils. It has to say a society devoid of racism, classism and gender oppression, so that no one has an unfair advantage because of that.”

The dialogue wound through other examples of systemic institutional and cultural oppression, not only racism, but also classism and gender differences, a matrix of oppression that affects all of us.

Despite the complexities of systemic societal problems demanding complex solutions, Evans and his current choir agreed that a good starting point for all solutions no matter how complex is answering: Do you see the person?

EVM staff writer and columnist Robert R. Thomas can be reached at captzero@sbcglobal.net.

You must be logged in to post a comment.