By Harold C. Ford

This piece has been updated to add information about a Partnership Agreement with the State of Michigan triggered by the district landing in the bottom five percent of state schools and thus falling into the category of “chronically failing schools.” Implementing strategies to address discipline issues in the schools is central to that agreement–Ed.

It’s hardly a secret. The larger community knows there are continuing and unresolved problems with discipline in Flint Community Schools (FCS).

Flint parents have “voted with their feet” on this matter, and others, by enrolling a majority of their youngsters in other area schools. Some of those that have remained attended large community meetings at the beginning and end of the 2018 calendaryear to address concerns about discipline. Discipline issues have frequently been the subject of comments by parents, employees, and board members alike at FCS Board of Education meetings.

Looming in the background is a lawsuit and a damning report by the American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan (ACLUM) about how Flint disciplines its children. All of this is in addition to budget shortfalls and the suspected insidious effects caused by a lead-infused water crisis. Added to that is the make-or-break challenge of a three-year partnership agreement with the State of Michigan that aims to reduce out-of-school suspensions by 10 percent as one of the district’s three main rehabilitation targets.

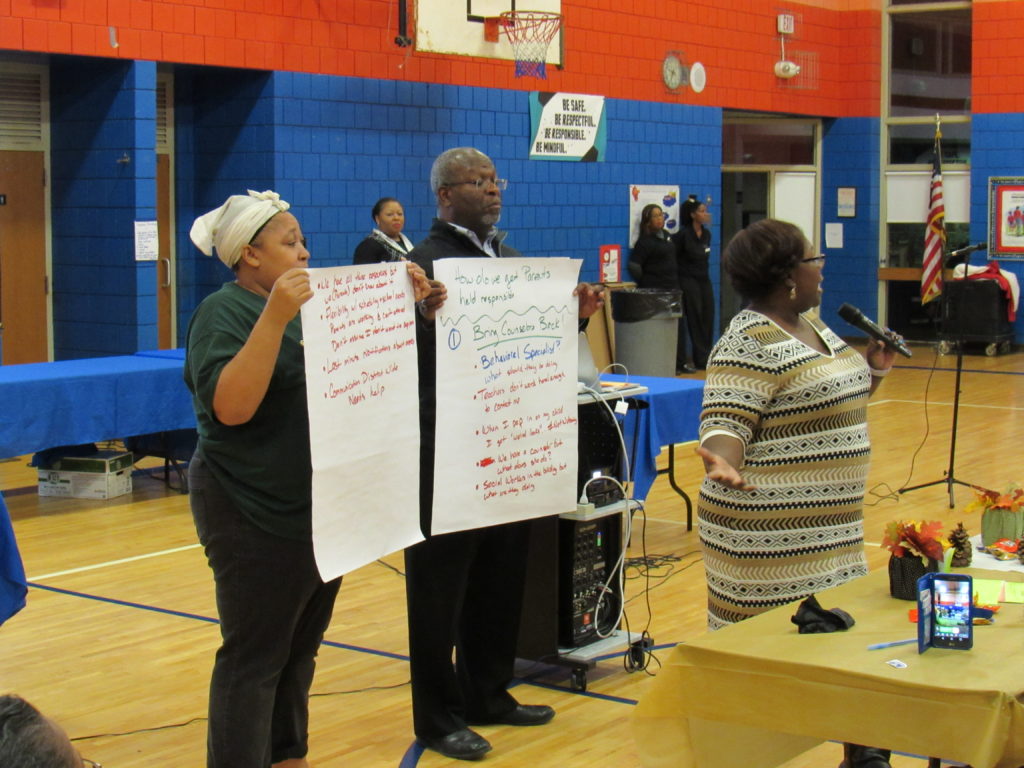

Title-1 City-Wide Parent Meeting, Nov. 14, 2018, at Doyle-Ryder Education Center (photo by Harold C. Ford)

Timeline:

A timeline of key events leading up to, and through, the 2018 calendar year might include the following:

- October 2009: The ACLUM issued a report on school discipline titled “Reclaiming Michigan’s Throwaway Kids: Students Trapped in the School-to-Prison Pipeline.” The report is based on 213 pages of discipline data collected from 22 Michigan school districts including Flint.

- April 2014: Flint’s water source was switched to the Flint River. The river’s corrosive and untreated water began to leach lead and contaminants into Flint homes and schools.

- October 2015: A 7-year-old male student is handcuffed by a school resource officer (SRO) during an after-school event at Flint’s Brownell K-2 STEM Academy.

- January 2018: Under the aegis of Community Based Organization Partners (CBOP), ACLUM representatives met with 40 to 50 Flint citizens to discuss discipline in Flint Schools.

- April 2018: Flint’s board of education adopted a security budget for its schools in the amount of $651,566. Of that amount, $385,000 was intended for safety advocates (SAs). The budget included the continued implementation of Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS), a district-wide system of behavior management.

- July 2018: ACLUM filed a lawsuit against the City of Flint and the Flint & Genesee Chamber of Commerce over the October 2015 handcuffing of a seven-year-old student.

- July 2018: FCS signs on to three-year make-or-break partnership agreement that includes reduction of school suspensions by 10 percent.

- August 2018: Derrick Lopez was hired to a three-year contract as the new superintendent of the Flint Community Schools.

- November 2018: Some 90 to 100 persons participated in a Title-1 city-wide parent meeting at Doyle-Ryder Education Center to discuss discipline and suspensions in Flint Schools.

Derrick Lopez (Photo from Flint Community Schools)

Lopez, ACLUM seem on same page vis-a-vis school-to-prison pipeline:

Though viewing the matter of school discipline from different perches, Flint’s new superintendent, Derrick Lopez, and the ACLUM seem to be on the same page in terms of seeing a link between non-restorative discipline and incarceration.

Lopez opened Flint’s November 2018 Title-1 meeting with a clarion declaration: “We are not going to be fostering the school-to-prison pipeline any longer.” Later in the meeting he explained, “Discipline requires teaching and correction. Punishment requires retribution which means literally putting them (students) out or pushing them away because you don’t want to work with them anymore.”

“Studies show that when students are repeatedly suspended, they are substantially at greater risk of leaving school altogether,” ACLUM’s press statement announcing its “School-to-Prison Pipeline” report in October 2009 said. “In at least one study of the Grand Rapids School District, 31 percent of students with three or more suspensions before spring semester of their sophomore year dropped out, while only six percent of students with no history of suspensions dropped out.” And, “68 percent of Michigan’s prisoners are identified as high school dropouts.”

School discipline and racism:

Community members share ideas about discipline with the help of Flint Superintendent Derrick Lopez (center) at Title-1 City-Wide Parent Meeting, Nov. 14, Doyle-Ryder Education Center (Photo by Harold C. Ford)

According to Kary Moss, then-executive director of ACLUM, the “School-to-Prison Pipeline” (STPP) report “documents and analyzes data that shows how the frequent use of suspensions and expulsions contributes to our high drop-out rate and how those suspension practices hit black students the hardest, putting them on a high-risk path to incarceration.”

“In school district after school district, from one end of the state to another, we found that black kids are consistently suspended in numbers that are considerably disproportionate to their representation in the various student populations,” Mark Fancher, ACLUM racial justice project staff attorney, said.

“More alarming still are studies we examined that show that the behavior of black kids and white kids is essentially the same, and black kids are kicked out of school proportionately more often,” Fancher added.

Disaggregated Flint data from the ’06-’07 school year showed significant disparities for suspensions in terms of race. While black students comprised 84 percent of the student population, they received 92 percent of suspensions from school. White students represented 14 percent of the district’s student population and received seven percent of the suspensions. Flint expelled 53 students during that same school year; all were black students.

In the Ann Arbor School District during the same school year, black students comprised 18 percent of the secondary student population, but received 58 percent of suspensions.

Data used in the report was accessed via the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) from Flint and 21 other Michigan school districts for the ’04-’05, ’05-’06, and ’06-’07 school years. Reasons for suspensions included: fighting; insubordination; disrespect; continued disrespect in class; loitering; truancy and tardiness; snap suspension; physical assault on a student; disruption of the educational process; repeated violations of the student code; and threatening and intimidating acts.

Flint part of larger national dilemma:

Flint is hardly alone in trying to figure out how to manage the behavior of its schoolchildren in a way that is not injurious to the intrinsic purposes of education. A 2018 report produced by the ACLU with UCLA (Center for Civil Rights Remedies, Civil Rights Project) analyzes data collected from 96,000 public schools in the U.S. Some excerpts of its findings:

- “Dramatic disparities exist at the school, district, state, and national level. Black students were just 15 percent of students nationally, but they accounted for 45 percent of all of the days lost due to suspension.”

- “This discipline gap contributes to the achievement gap. The 11 million days of lost instruction translates to over 60,000 school years, over 60 million hours of lost education, and billions of dollars wasted in a single school year.”

- “Although schools reported over a million ‘serious offenses’ in the 2015-16 school year, over 96 percent of these concerned fights, physical attacks, or threats without weapons. Only three percent of the million offenses actually involved a weapon, and less than three percent of all public schools reported any incident of physical attack or fight with a weapon.”

- “Also, up to 1.7 million students were in schools with cops and no counselors, and over 10 million students were in schools that reported police officers (also called school resource officers) and no social workers in the 2015-16 school year. Nationally, schools reported 27,000 sworn law enforcement officers compared with just 23,000 social workers.”

- “In 2015-16, Black students represented 15 percent of enrollment nationally, but 31 percent of students referred to law enforcement or arrested. This is actually an increase from the 2013–14 school year where Black students were 16 percent of the student enrollment and 27 percent of students arrested or referred.”

Handcuffing illustrates potential excess of punitive discipline:

In October 2015, a seven-year-old student who misbehaved during an after-school event at Flint’s Brownell K-2 STEM Academy was handcuffed by a Flint police officer who was employed as a school resource officer (SRO). The after-school program was administered by the Flint & Genesee Chamber of Commerce.

In July 2018, the ACLUM filed a lawsuit on behalf of the student and his mother against the City of Flint, the police officer, Flint’s police chief, and the chamber. The suit alleges excessive force and disability-based discrimination. The lawsuit was filed in Flint U.S. District Court and claimed that Cameron McCadden was approximately four-feet-tall, weighed 55 pounds, and was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

The suit also claimed that McCadden was cuffed for about an hour until a key was found and the boy was released. An order to stop the restraint of children with disabilities and unspecified and punitive damages were sought.

According to ACLUM’s Fancher, students with disabilities are only 12 percent of the national public school student population, but they account for 75 percent of students subjected to physical restraint in schools. “In addition, while African-American students like Cameron are only 19 percent of students with disabilities, they account for 36 percent of students subjected to mechanical restraints like handcuffs.”

Lopez, Flint’s new superintendent, called the ACLUM lawsuit “rabble-rousing.” Lopez told East Village Magazine, “I wasn’t here when that occurred, but I can imagine how a parent felt when their child was handcuffed in the school building. That cannot sit well. The goal for us here is to address those issues proactively so that doesn’t happen again.”

ACLUM study concludes officers in Flint schools are mostly subs for school personnel:

Some 40 to 50 Flint citizens, present at a meeting called by Community Based Organization Partners (CBOP), were told by ACLUM representatives that Flint police officers serving as SROs in Flint school buildings were mostly subbing for other school personnel. ACLUM Campaign Outreach Coordinator Rodd Monts said, “they (police officers) are clearly doing a lot of things that I don’t think their contract calls for.”

Monts claimed that Flint SROs spend a great majority of their time on matters other than safety. He said that about 80 percent of SRO time in the high schools was spent on non-safety matters; that number grew to 90 percent in the elementary buildings. Based on ACLUM’s analysis of 1,000 pages of officer’s logs accessed by the FOIA, SRO time was spent in the following ways:

- 33 percent of the time was spent counseling;

- 31 percent acting as administrator;

- 26 percent policing after-school programs;

- Eight percent handling student misconduct;

- Two percent protecting students and staff.

One community member at the meeting agreed that police officers in Flint schools are often put into positions they don’t necessarily welcome. She claimed to have heard “complaints from police officers who are saying that they are ‘catch-all’ (employees). They’re put into positions of psychologist, social worker, counselor, etc.”

“When we say get the police out of elementary schools,” Monts said, “we’re saying take that money and invest it in professionals who can address some of the reasons that kids are finding themselves in contact with police in the first place.”

Concerns over discipline likely one cause for loss of students:

Expressions of concern about the social climate of Flint’s school buildings and student discipline are ubiquitous:

- One parent at the January 2018 CBOP meeting remarked about “a hostile (Flint) school” where she witnessed “a kid slapped a teacher so hard that she was wearing a neck brace.” The parent claimed “the kids are very violent in some of those schools. Even in the elementary, the parents are so violent the teachers need a police officer there to keep them from beating them up.”

- At its April 2018 meeting, Flint Board of Education President Diana Wright observed, “When we have visitors to all our schools and one of the first things they say is, ‘People are everywhere, out of order, and not where they’re supposed to be.’ Why can’t we get people where they need to be?”

- Superintendent Lopez admitted at the November Title 1 parent meeting in November 2018, “We’ve got some thunder cats (students who misbehave). I’m not confused at all.” But he quickly added, “We have to make sure that we’re caring and loving for them through this [thunder cat] space.”

- At that same November 2018 Title 1 meeting, one school employee told EVM, “If it ain’t broken, don’t fix it. This system is broken.”

- A frustrated Flint parent who works as a sub teacher in Flint schools pulled her child from the very school system she is employed by. She told those at the January 2018 CBOP meeting, “I’m educated, I’m single, I’m not on welfare, I stay in Flint, my son went to Flint schools. Where do I go from here?”

That frustrated Flint parent is hardly alone in pulling her child from Flint’s public schools. It is stunning that only one-third of Flint’s students are enrolled in FCS. Some 10,000 of Flint’s 15,000 school-age children are not enrolled in Flint schools. About 5,000 attend charter and private schools. Another 5,000 opt for Schools of Choice and attend mainly suburban schools.

On its first student count of the 2018-2019 school year, Westwood Heights reported that 67 percent of its students have Flint addresses. It is remarkable that Flint is now the fourth largest school system in Genesee County behind Grand Blanc, Davison, and Carman-Ainsworth.

Water crisis likely exacerbates challenging student behaviors:

Flint’s infamous water crisis likely exacerbated the challenging behaviors of some of its children. When Flint switched to the Flint River as a water source in 2014, lead-tainted water leached into thousands of Flint homes and its public school system. Flint schools still rely on expensive bottled water that is paid for by charitable contributors.

And the science is clear about the damaging impact of lead-tainted water on the behaviors of children. Author Jamie Lincoln Kitman wrote in the March 20, 2000 edition of The Nation:

“Children are the first and worst victims of (lead); because of their immaturity, they are the most susceptible to systemic and neurological injury, including lowered IQs, reading and learning disabilities, impaired hearing, reduced attention span, hyperactivity, behavioral problems, and interference with growth.”

Flint schools face quandary

So Flint schools are caught between the proverbial rock and hard place: How to restore/maintain social climates in its school buildings that are conducive to learning while overhauling its disciplinary system so as to reduce suspensions, expulsions, and lost days of instruction?

Several key parties are on board with the goal of reducing suspensions and expulsions including the new FCS administration, the ACLUM, and the signatories to a three-year partnership agreement (PA) that was inked in July. As reported in the September 2018 edition of EVM, the PA “was forged between FCS and the Michigan Department of Education (MDE), the State School Reform/Redesign Office (SRO), and the Genesee Intermediate School District (GISD).”

Key members of the PA, in addition to FCS, include the Flint-based Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, the Crim Fitness Foundation, Michigan State University, and the Concerned Pastors for Social Action.

The three main goals of the three-year PA are significant and clearly interrelated:

- reduce out-of-school suspensions by 10 percent;

- increase student attendance to 90 percent;

- increase course/state exam performance by 10 percent.

Toward those goals, FCS has invested, in part, a significant portion of its annual budget into security personnel and an overarching system of building/classroom management.

FCS budgeted $651,566 for building/classroom management and security in 2018-2019:

At its April 2018 meeting, the Flint Board of Education approved an expenditure for building/classroom management and security in the amount of $651,566. Of that amount, $385,00 was designated for Safety Advocates (SAs). According to Ernest Steward, director of student intervention, SAs have responsibility for “securing the building, the premises, and making sure our staff and students are safe.”

Included in the aforementioned line item of the FCS budget is support for a program of building/classroom management titled Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS). Steward told board members, “All of our safety advocates have been trained in PBIS restorative practices and those are relationship-building types of initiatives that we have to reduce our suspension rate as well as develop and build relationships between staff and students.”

According to its website, PBIS aims “to improve the effectiveness, efficiency and equity of schools and other agencies. PBIS improves social, emotional and academic outcomes for all students, including students with disabilities and students from underrepresented groups.” PBIS is funded by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Special Education Programs and the Office of Elementary and Secondary Education.

New FCS administration moves ahead:

No matter the measures already in place, the new administration at FCS—Superintendent Lopez and Assistant Superintendent Anita Steward—headed up a Title-1 City-Wide Parent Meeting on discipline and suspensions at Doyle-Ryder Education Center on Nov. 14, 2018. “So the work of this meeting is to literally hear from our parents…about our discipline policies with respect to their children,” said Lopez at the start.

For two hours, some 90 to 100 FCS parents and employees brainstormed about the problems of discipline in Flint schools and how to fix them. Smaller work groups jotted their ideas onto poster paper which were then presented to the larger group. Roughly, concerns and suggestions targeted school personnel, students, parents, and communication issues. A second Title 1 meeting in January 2019 will provide analysis of the November meeting and move forward from there.

Lopez closed the session with an admonishment: “We have entrapped and dehumanized our children to such a degree that we don’t even begin to think about them as children. We think about them as behaviors.” Nonetheless, he said, “If a child misbehaves they definitely need discipline.”

Recognizing the complicated task of both loving and disciplining our children, Lopez referenced his grandmother who, when he misbehaved, told him, “Boy, I don’t really like you right now, but I love you. She made sure I was disciplined so that I could realize my promise.”

EVM Staff Writer Harold Ford can be reached at hcford1185@gmail.com.

FCS Superintendent Derrick Lopez (photo credit: FCS website)

You must be logged in to post a comment.