By Jan Worth-Nelson

This story was updated Jan. 13 to add more of Highsmith’s comments and a link to an EVM review of Demolition Means Progress, available here.

At first blush, historian and author Andrew Highsmith told a responsive and appreciative audience of 70 at the Flint Public Library Saturday, the Flint of 1954, when General Motors sponsored an extravaganza called the Golden Carnival, was a city “perched on top of the industrial world.”

At first blush, historian and author Andrew Highsmith told a responsive and appreciative audience of 70 at the Flint Public Library Saturday, the Flint of 1954, when General Motors sponsored an extravaganza called the Golden Carnival, was a city “perched on top of the industrial world.”

On that November day when 150,000 people lined Saginaw Street for a parade featuring a gold-plated Chevy BelAir and GM president Harlow Curtis announced a $3 million gift to fund the city’s cultural center, it seemed Flint was the nexus of “a golden age of sorts for American capitalism and prosperity.” The city was, after all, the home of close to a quarter million people, with 80,000 employed by GM, with impressive wages, low unemployment and nationally-recognized public education.

However, Highsmith asserted, “Although the splendor of the day made it difficult to detect,” that event “concealed just as much as it revealed.”

“Beneath the shine of the Golden Carnival, Flint was a profoundly segregated and unequal city,” he said, “and the municipal and corporate officials who presided over the day’s amusements were largely to blame.”

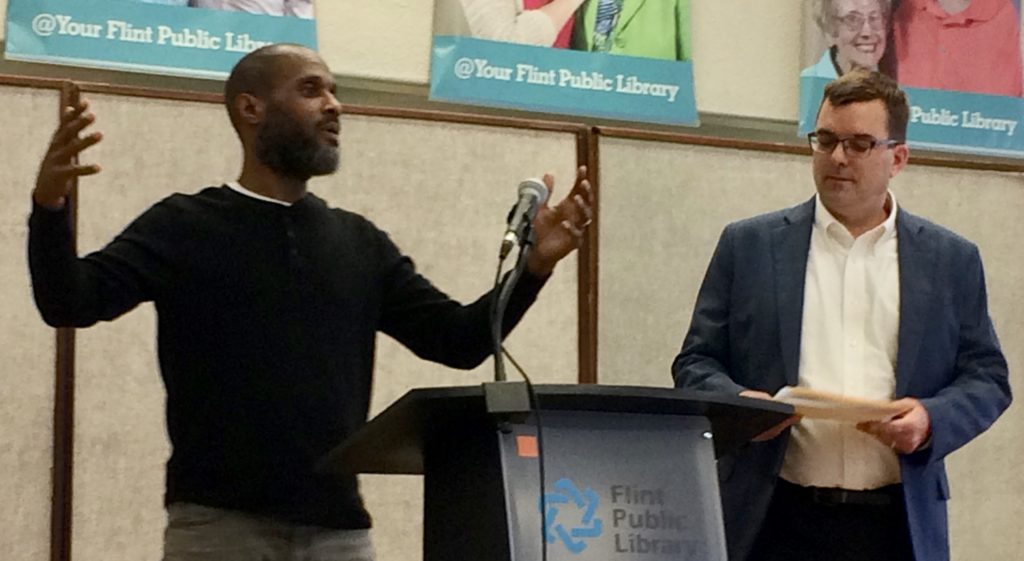

Community Read moderator Todd Womack (left) introduces Andrew Highsmith Saturday at the Flint Public Library (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

That story–“Flint being one of the most starkly segregated and racially unequal metropolitan areas in the entire nation,” — continues to this day. Three successive maps on a screen for the audience to see–from 1950, 1980 and 2010–made continuing “hyper-segregation” of African-Americans visually unmistakable.

Highsmith is the author of Demolition Means Progress: Flint, Michigan and the Fate of the American Metropolis. [Read a review of the book by EVM writer Robert Thomas here] Now a professor at the University of California at Irvine, Highsmith began his book as a Ph.D. dissertation in 2003 when his wife, a physician, was working in Flint and the couple bought a house on Paducah Street in Mott Park. His talk and visit to Flint were part of the Community Read, a project focusing each year on one book which Flint residents read and discuss at monthly gatherings.

In buying their house, built by GM in 1927, the Highsmiths were given a box of legal papers — among them an old deed restriction set by GM indicating originally the house could only be sold to whites. That discovery propelled him into his research. He noted his wife, who is Indian, was the first person of color to live in the house.

His most significant finding, he said, was the history, persistence and contributing factors to the “color line.” He emphasized Flint’s racial divisions go back a long, long way.

Community Read facilitator and UM – Flint professor Erica Britt helps capture discussion points (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

“Achieving this level of segregation wasn’t easy,” he said. “It required in fact a great deal of effort from a variety of people and institutions. It didn’t just happen naturally, it required hard work. It took widespread use of restrictive housing covenants, it took numerous acts of violence. It took realtors, lenders and builders who did their part by steering African-Americans away from white neighborhoods.

“But racism in the private marketplace wasn’t enough to maintain Flint’s rigid color lines. In fact, government at all levels played a role too. In the first half of the 20th century in fact, courts routinely enforced racially restrictive deed restrictions, officials from the Federal Housing Administration(FHA) also did their part by preventing African-Americans from obtaining home mortgages.

City officials, he contended, maintained the color line through discriminatory education practices, urban renewal, and public housing programs. “In Flint,” he concluded,”racial segregation was public policy for much of the 20th Century.”

Raised in Cincinnati, Highsmith said he grew up with the concept that “in cities of the north, segregation was de facto — prejudice from people’s hearts and minds.

“And yet I found in Flint, there was public policy driving much of that inequity. This led me to believe that we need to jettison the concept of de facto segregation once and for all.”

While Flint’s story appears to be a very familiar tale of urban decline,” Highsmith said, “the reality is much more complicated–” ironically, sometimes the result of a drive toward renewal.

“Flint’s story is best understood as one of renewal — a history driven by the near-constant and yet unfulfilled struggle to grow the local economy and revitalize the city”–a philosophy, often with dire consequences, that lies behind the slogan “Demolition Means Progress.”

The statement comes from signs GM used to put in front of its shuttered factories, he explained.

“It doesn’t represent my feelings,” he said. “I thought it was a ridiculous corporate slogan, but over time I came to learn that ‘Demolition Means Progress’ was a powerful metaphor for thinking about the city’s history– the operating ethos of the area’s economic and political leaders for most of the 20th and early 21st centuries.

Danielle Brown, program director for the Flint Genesee Literacy Network, leads a small group discussion at the Community Read event, with Tony Palladeno, Nayyirah Shariff and Doug Jones (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

This philosophy not unique to Flint, he said. Many civic and economic leaders “have looked to demolish what they perceived to be old and inefficient structures and institutions and to rebuild them to be more profitable: they demolished poor and African American neighborhoods and replaced them with freeways and public housing,”

They tore down old factories, rebuilt them in the suburbs, with “really grave consequences.”

“Civic and political elites ultimately hardened social inequality, making Flint one of the most racially segregated, economically polarized and politically divided metropolitan regions in the United States.

All of it was rooted, he said, in Flint’s “virtually ceaseless quest for revitalization.”

And the logic that “growth anywhere will benefit everyone in the metropolis didn’t pan out to be true,” he said. “Ultimately, suburbanites did not share those resources, hoarding the tax base away from the people of Flint for themselves.

“Logic based on a sense of cooperation has been very difficult to leverage for quite some time,” he said.

Anna Clark of Detroit, author of The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy, came to Flint to meet Highsmith and join in the discussion–here with Highsmith and Flint resident Ray Heddy (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

If he could add anything to his book, Highsmith said, it would be to add a chapter on the Flint water crisis. His manuscript went to the publisher in the spring of 2014, just as Flint switched to river water, and the book came out in the late spring of 2015–just as Flint was starting to make headlines. None of that story appeared in his book.

If he could write that epilogue, he said, the essence of it would be “The Flint water crisis didn’t begin in 2014, and it’s not over yet.”

“We already know a lot about government malfeasance– the contamination of the water supply has been well documented, but there are larger and deeper issues.

“Beyond the misdeeds of officials who triggered this calamity,” he said, “Flint’s crisis is also the product of variety of larger historical forces.” The city’s water and infrastructure troubles also stem from generations of government-sponsored deindustrialization, white flight and disinvestment, forces that have eroded the tax base making it all but impossible to update or even maintain the city’s infrastructure.”

And the emergency manager system installed by the state made things worse, he said. “Only city residents lost the right to self-governance. Only city residents experienced the toxic exposures.

“This was not not some kind of demographic accident. The water crisis is inextricable from our longer histories,” he said, concluding, “we’ve really got our work cut out for us.”

As part of the design of the event, Community Read committee members divided the audience into eight tables, where small groups were offered two questions and discussed aspects of Highsmith’s book and reported back to the whole group.

At a Q&A session concluding the event, members of the Flint audience expressed thanks and admiration for Highsmith’s work and agreement with his findings.

“Your book is the only thing that has grabbed my attention since Mad Magazine,” Eastside activist Tony Palladeno said. “You’ve nailed it so much. We are tired. The people that should be helping us aren’t, and some of us are fighting each other now.”

Community activist and UM – Flint lecturer Laura MacIntyre told him, “People finally feel validated” by the findings of his work.

Reflecting on the overall event, Community Read Committee member and moderator Todd Womack, a lecturer and academic advisor in social work at the University of Michigan – Flint, said, “We believe that a community of critical thinkers engaged in wholehearted, vulnerable and transparent relationship with one another can move this city to a place of accountability and wellbeing for all Flint residents,” ]

Moving forward, he said the Community Read planning group hopes to grow the number of attendees, increase the number of residents who have a sense of belonging at the “Read,” increase the number of residents who learned something new, and enhance residents’ intellectual skills.

The Community Read project is sponsored in part by the University of Michigan – Flint, the Flint Public Library, the Flint Genesee Literacy Network, and Flint ReCAST. Other books featured have been Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness and Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me.

The next discussion on Demolition Means Progress is scheduled for 11 a.m to 1 p.m. Saturday, Feb. 9 at the Genesee Valley Center Library. More information available at facebook.com/CommunityReadFlint or 810-232-2526.

EVM Editor Jan Worth-Nelson can be reached at janworth1118@gmail.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.