By Jan Worth-Nelson

Charles Boike long ago gave up his “life of crime” in the name of art.

But Boike, 36, who has been described as an “urban graffiti artist at heart,” definitely has not given up his life of art.

Now a practicing attorney with a wife and baby daughter, the Fenton artist has been for years creating high energy, vibrantly colorful murals all over Flint, from Buckham Alley to Totem Books to the Farmers’ Market to Table and Tap to Habitat for Humanity to the corner of Twelfth and Fenton roads.

In the parlance of the street artists whose inclinations he still identifies with, Boike is “getting up” in the city.

And the effects of that work, along with the work of other artists from the street arts like his painting partner Kevin Burdick, Pauly Everett, and the muralists coming to town through Joseph Schipani’s Flint Public Art Project, are a substantial and powerful body of public art.

He confines himself these days to “permissible walls,” as he puts it, working on commission and often interacting with the property owners about color, design and subject.

That is a change from the days when he would sneak out in the middle of the night, with a supply of spray cans, a crew and assistants offering surveillance against getting caught, to tag railroad cars and subversively blanket unsuspecting walls.

That era of his life, he said, appealed to a craving for freedom and self-expression.

Charles Boike talking about his work at a lecture with a Sammy Davis, Jr. triptych in the Mott Community College Fine Arts Gallery. The show ran through April 23 (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

“Graffiti is an art form that is totally for yourself–even selfish,” he observed in an interview. “A graffiti artist is never given an assignment — The only rule is to come up with an identifying mark, a moniker–your first step is to come up with something that’s YOU.

“It’s about having your own style–you’re not told what to paint–you create a name and then you go out and paint your name, and then you think of other things you want to paint and then you go out and paint them.”

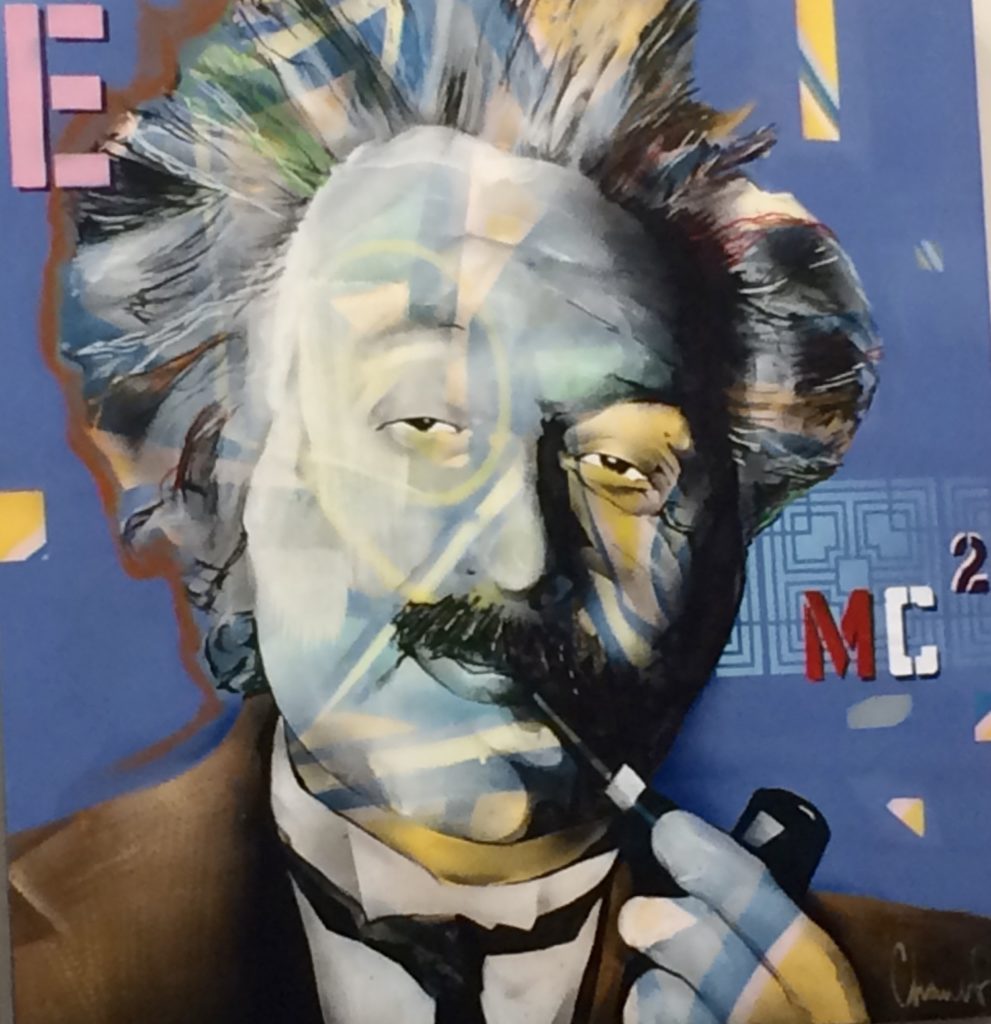

Albert Einstein a la Charles Boike (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

The graffiti artist “is not thinking about what the community wants to view, or what the business owner wanted on his property–there are no discussions with anybody but your own internal discussions about what to create,” he said.

He was a teenager when his graffiti life bloomed, and he did get caught.

“Unfortunately I got into some trouble and had to repent,” he said. He got arrested in Flint, East Lansing, Detroit, sentenced to “large restitutions,’ many hours of community service–“it went on for multiple years with multiple agencies involved,” he said–and though he luckily was a minor during these years of confrontation with the law, the repercussions did extend into his adult life, he said, when he had to explain himself and his legal history in formal detail to be admitted to the bar.

But that is not Boike now. His work since then has been strongly devoted to supporting the community and bringing art where people live and can see it.

Early on, Boike gave himself the name “Wake Up,” sometimes just “Wake” with the “E” in Wake often prominently favored –and in fact still uses the moniker.

His tag name “probably” has “some existential meaning,” he said with a smile. “I just thought sometimes people need to wake up. Graffiti has always been about acts of rebellion, cultural rebellion. I think people need to realize they have more blessings than they know — and also should have a healthy disrespect for things” until they’re proven.

“Waking up,” he said, “might lead to more education and self-realization, which makes you happier in life. The better you know yourself, the more comfortable you can be in your own shoes.”

Boike with one of his most recent “High Profile” portraits (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

And even though “Wake Up” still appears on some of his work and is how he’s known in the street art world, now that he’s legal he also can use his actual name without fear of prosecution.

The change to “legal art” has not meant an abandonment of his aesthetic or the drive for self-expression –he still vigorously asserts his right to free speech and to explore the potential of the spaces his work inhabits.

“I’m inspired by the choice of freedom, exercise of free speech, bright vivid colors and anything that breaks away from traditional mindset,” he wrote in his artist statement accompanying a show that concluded April 23 at the Mott Community College Fine Arts gallery.

“I feel a need to create a legacy of how I interpret my existence,” he wrote. “I use my paintings as a vehicle to create conversations within an individual by finding ways to juxtapose traditional and non-traditional elements.”

The Mott exhibit revealed Boike art on a different scale than the murals –16 three-by-three-foot spray paint and acrylic canvases.

Boike’s take on Richard Nixon (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

Called “High Profile,” the show featured portraits with a pop-art flavor of Nixon, JFK, Audrey Hepburn, Carl Sagan, Albert Einstein, Nelson Mandela, Sammy Davis Jr., and Marilyn Monroe. Not to mention a Flint high-profile celebrity, the Vernor’s gnome.

The MCC works echo Boike’s love of the unlimited wall. Even though the canvasses are comparatively small and side by side, he points to how many have lines seeming to go off the frame, suggesting there’s something to look at in the wall, arrows to the adjoining space, something else beyond the limits. The works, even at their most traditional, thus have an open, unbounded feel.

Talking about the portraits in the Mott show, Boike used words like “rhythm”–the lettering and paint strokes having “movement,” –and one sees the impulse of the graffiti artist, working fast in the dark and leaving something surprising to be discovered in the morning.

Beyond the stylistic elements, too, Boike’s evolution into the gallery and commercial realm has offered challenges he said he welcomes–offering financial rewards, of course, but also introducing degrees of aligning visions when working with potential buyers.

And he remains fond of the audacity and drive of taggers. He said he thinks the competitiveness of the commercial art world is something a graffiti artist is uniquely suited for.

He said he recalled an acquaintance noting, “A street artist already is willing to commit a crime to put up his art.”

“If you’re not willing to do that,” Boike said, “you don’t have the same drive and ambition that would be required to compete in the marketplace.

“Who is more hungry for the job? If he’s going to do it illegally, he’s pretty hungry. That is my lineage,” he said.

Street artists also have to cope with challenges by other street artists — those who paint over their work or claim their territory after the fact. Overall, he said, he’s now “old school” enough that he’s generally respected by other artists. But not entirely: a commissioned mural he did for the Eastern Market in Detroit was vandalized and remains to be repainted.

That’s one advantage to working on commission for individuals in their homes. When he puts up his artwork, he says, “I own that wall” and nobody can mess with it. He said he enjoys the give and take with clients. Most of the time they know his work and that’s why they approach him to start with, so there often are commonalities between what he does and what they want. The differences often can be negotiated.

“In my mind I’m lucky,” he said. He calls that kind of relationship with his clients “a fair exchange.”

One of Boike’s favorites in the MCC show: George Harrison (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

Boike’s professional journey took him from Powers Catholic High School (“school just wasn’t for me” though he did ultimately graduate) to years of working in bars, representing musicians and playing in a jazz group, The Macy Trio, moving from Flint to Lansing to Chicago and back.

“My dad told me, you don’t want to be working in a bar all your life because the hours suck,” he recalled. Eventually he got in to Chicago’s Columbia College, majoring in art and media management, and started performing more, headlining in the Flint Jazz Festival in 2009.

Still he was a starving artist, and his mother advised, “You’re trying to be Eminem and that didn’t work out — maybe you should be Eminem’s attorney.” So he enrolled at Cooley Law School and was admitted to the bar in 2012.

He’s now house counsel at Progressive Insurance, most often litigating issues around auto accidents.

And sometimes at night, after the baby and his wife are both asleep and he knows “everybody’s safe and sound,” he’ll get up and go into his garage and paint, sometimes until 3 a.m.

“But then I’ll stop and say to myself, wait, I have to go to work in the morning!” and he’ll put away his spray paints and vivid palette for another day, another wall.

Banner image of Albert Einstein’s hair, from Charles Boike’s portrait (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson–permission to “excerpt” given by the artist.)

EVM Editor Jan Worth-Nelson can be reached at janworth1118@gmail.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.