By Jan Worth-Nelson

By Jan Worth-Nelson

Facing lies, atrocities and daily affronts to self-love and spiritual peace, “we have to tap that eternal spring of regenerative light,” Flint poet, artist, musician, scientist and activist Semaj Brown implored a rapt audience Aug. 21 at the Mott-Warsh Gallery, 815 Saginaw St.

Brown, who moved to Flint from her hometown Detroit in 2003 after marrying local family physician James Brown, combined readings of a half dozen poem and prose pieces and a conversation with University of Michigan – Flint linguistics professor Erica Britt.

It was a wide-ranging, 90-minute program exploring connections between art, science, mythology, music, fierce assertions of personhood, and appeals to the ancestors. And it ended with a standing ovation.

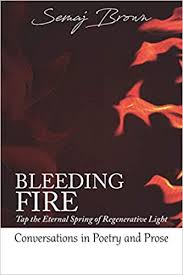

The event celebrated the publication this year of Brown’s first collection, Bleeding Fire: Tap the Eternal Spring of Regenerative Light, published by the venerable Broadside Lotus Press in Detroit and Health Collectors LLC.

Semaj Brown from Women of a New Tribe, photo by Jerry Taliaferro, 2016, Digital print © Jerry Taliaferro. Used by permission of the Flint Institute of Arts.

Born in 1960, Brown calls herself part of the “progeny” generation of the Broadside Lotus family, emerging after the “legacy” poets of the 60s and 70s including Dudley Randall, Sonia Sanchez, Haki Madhubuti, Audre Lorde, Etheridge Knight and Gwendolyn Brooks

Further described on the cover as “Conversations in Poetry and Prose,” Brown’s idiosyncratic collection combines memoirs of her mother, the classical pianist and scholar Bessie L. James, along with dreams, recreated and transformed myths, commentary on the “Me-Too” movement, reflections on connections between science and art and more, offered up in six sections.

The six are: Black Holes and the Beacon, Conflagrations and Transgressions (Me Too), Radioactivity, Infernos and Inspirations, Flame and Flares, and Fusion.

The work, as Britt summarized it, is hot and full of “space, energy and light.” Brown said the title came to her in a dream, after her husband, whom she referred to throughout as “Dr. Brown” in a combination of respect and adoring, wry acknowledgement, kept asking her “Why don’t you have a book?”

And her titles reflect her scientific background; she graduated from Wayne State with a degree in biology and taught science in the Detroit Public Schools, creating innovative science education curricula statewide and nationally.

“Science is my work; art is my work — I really don’t see the difference,” she said, asked by Britt to reflect on her omnivorous background and body of material. “It is all one–it’s all connected in my world.”

Music too is part of it. Growing up in the culturally-rich home of a Pan-Africanist mother determined to teach her daughter to know her history, to know nature, to be self-reliant, and to “know how to see,” Brown learned to play the violin along with conducting scientific experiments in her basement.

Some of her creations are manifestos and credos for young women, as in her 11-part poem “Roar (Rhymes of Applied Rights)” when her speaker rhymthically and forcefully asserts, “I imitate no one/I am the sole one/I am unique/If you can’t see me/then, you cannot see/Glasses are what you need” and later, “I’m not honey/I’m not sticky/Just call me by my name/Respect will come more quickly.”

She continues, “Violence against me/you should dread/Tables have turned/I’ll leave you for dead.”

“We need new rhymes,” Brown told Britt in explaining the “nursery rhyme” flavor of the poem. “We need to know how to own ourselves. We’ve been trained to be polite, but we also have been trained to have a voice.”

And a powerful voice it is, filled with muscular, mesmerizing diction, audacity, humor tinged with a bite, eroticism, and fearless challenges to subjugation. Many of the poems are cries of the heart in answer to trauma, indignity, and abuse.

In her poem “I will,” declaimed breathtakingly to the Mott Warsh audience, her speaker cries out:

“After you drive your truck through me/I will not settle like dust on a road…I will not/shrink into a bowl of scarlet sauce/and pretend that it is not my blood/I will not/Forgive you for grinding the skeleton of small boned women/I will not/Play Billie Holiday’s “Good morning heartache,”/I will not/Carry the carry the pain of exaggeration in a papoose of bitterness/I will not…”

Asked about her process, Brown said she is often entreated by dreams and up at 3 a.m. — demanded by poems that want to be written, beseeching her to pay attention.

“It’s not fun,” Brown said. “If I could do something else I would.

“Sometimes it’s emotional, and you have to be ready for it. But I’ve been trained to manipulate it where it needs to go.”

One of her most deliciously vigorous poems of the performance was “Black Widow Spider (Part 1 and Part 2) in which her brazen narrator reports, “Today I swallowed Moon/He was a burnished meal for my widow spider cravings/he was culinary heat broiling willing flesh/He became the pop in my frying colon of hope/He became the orbit in my sweat lodge of desire…”

“My speech,” her black widow thrillingly asserts, “is a smudge stick of thought.”

Nonetheless, Brown told the audience, “I am so sick of the myth of the strong black woman. We can’t become our own mythology.”

Brown said in addition to falling in love with “Dr. Brown,” she has fallen in love with Flint. She has been deeply involved in helping her husband’s patients live healthier lives, co-founding with him the Planted Kingdom Project and Health Collective to promote community wellness.

As chapter president and with other members of the Pierians, she has implemented workshops on how protest art or art of resistance has affected struggles for freedom and self-determination historically. She has provided services to the Boys and Girls Club of Flint.

Her epic poem “Mother Ocean,” inspired by the portrait exhibit “Women of a New Tribe” by James Taliaferro at the Flint Institute of Arts (she was one of the subjects) has been presented both at the FIA and the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History.

Her epic poem “Mother Ocean,” inspired by the portrait exhibit “Women of a New Tribe” by James Taliaferro at the Flint Institute of Arts (she was one of the subjects) has been presented both at the FIA and the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History.

Her husband, a musician and composer as well as an M.D., has collaborated with her on many projects.

In introducing her, Britt said Brown’s work “has done something spiritual for me.”

“I was in a tailspin,” Britt said, “and it transformed me.” At the end of the evening, she came back to Brown’s theories of life and self-care.

“I try to stay in the present,” Brown said. “What’s happening to me right now–that has helped me so much. If you live in the atrocity you won’t survive. If you live in the present, you will not go mad.”

Brown’s book is available on Amazon and through Broadside Lotus Press.

MW Gallery is the new permanent home of the 700-piece Mott-Warsh Collection (MWC). The gallery’s mission, according to its website, is to “provide a welcoming environment for engagement with fine art created by artists of the African diaspora and those who reflect on it.” More information available here.

EVM Editor Jan Worth-Nelson can be reached at janworth1118@gmail.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.