By Melodee Mabbitt

On Halloween, I’ll have lived for 10 years in my house in the East Village, or what my mom referred to as “management’s neighborhood.”

I recently tried to explain to someone in the neighborhood how different my life was before I came here, when I lived on Bennett Avenue and later on M. L. King. I tried to explain the first violent crime I’d witnessed, and then the next one.

I don’t even know if I got them right. Was that the first one? The second? Wasn’t it in fact true that so much violence also took place before, between, and after? Why did I choose those two instances to retell?

There are two Flints in my experience.

One where you can try to explain the violence you’ve experienced by trying to cate-

gorize it: by murders? By attacks? By who died and you had to grieve? Or, by the more gruesome attacks you saw first-hand, but everyone lived? By how old you were when you went through it? Or by the age your friends were when they died? Or by the type of death? Guns or vehicular manslaughter or blunt force/stab wounds? Do overdoses even count among our losses?

And the Flint I live in now, in the College and Cultural Neighborhood, where no one has broken into our house yet, where the worst it’s ever gotten was when somebody once knocked but then ran away.

Sometimes when I am falling asleep, I dream of a hard knock, gunshot, or running feet, but when I wake afraid it always turns out I was just dreaming, afraid. Ten years and less than a mile from where I learned to be afraid, all is quiet and well living here between the politicians and attorneys, the Chamber of Commerce and university employees, with our Mott police coverage and additional private security.

Melodee Mabbitt’s childhood home — now boarded up (Photo by Melodee Mabbitt)

I could say that I started to feel unsafe around fifth grade, but I’m not sure if that is just because my awareness was dawning or because the late 80s drew in a new era of violence in Flint.

Either way, fear of violence felt like a more natural progression in my life than trying to relax in the safe places I’ve lived. One can only witness so many atrocities before it becomes impossible to leave those burdens behind by moving away. It widened my lens beyond any ability to simply focus on the positive and tuck in to material comforts.

An old friend from the east side thanked me for naming our experiences as trauma. For us, it was all a normal part of life at the time. Until I stop to reflect, it is easy to forget that people in this neighborhood spend their whole lives never knowing a murderer or someone who was murdered. I know several of each. People all over Flint do.

Each instance of violence carries its own haunts and ghosts in my mind, so it is hard to recall it all with a journalist’s accuracy. It all feels more like something I wear than something that I passed through and left behind.

I think I experienced my first violent death in sixth or seventh grade when my classmate was taken to the riverbank by some other boys we all knew, his cousins who had been playing at gangster. We were told that they’d cut out his tongue and shoved it up his anus before shooting him to death for talking to a rival gang. He was around 14, and I was around 12 when I heard all about it.

Maybe I experienced my next violent crime the summer after seventh grade. I was walking to the corner store with my best friend and we happened upon a teen I knew being disemboweled with what we later found out was his own knife. He walked, entrails dragging, right past us and around the corner to the gate of his family’s fence before he collapsed.

He lived, but my mom organized a peace march in response. Mayor Stanley and Prosecutor Busch came to speak at Homedale Elementary where our march ended in a rally to stop the violence.

It, of course, did not stop anything.

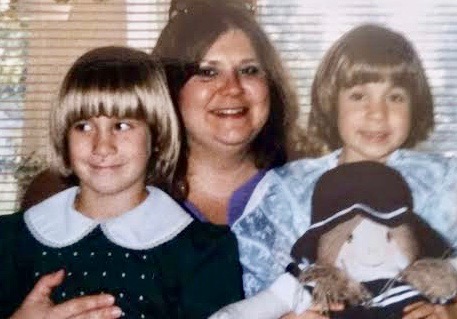

Left to right, Jennifer Hagensen, Linda Hagensen and Melodee Mabbitt at about age 7. Linda died in 2017 at age 67 (Photo from Melodee Mabbitt).

In ninth grade, our house was robbed and a girlfriend of one of the kids who broke into our house showed up to class wearing my clothes. I picked a fight with her, lost, and then never went back to Flint Central again.

The next year, my mom sent me to live with my aunt in the township to attend Carman-Ainsworth.

Through high school, I missed some of the drive-bys, people trying to break in with knives, holding the neighbor’s toddler who had just watched her father be shot for his weed stash, and many other events that my mother and sister experienced. I was just across town but it was a different world.

By the time of the arsons of 2010, I was already living in the Village when my mother called at 2 a.m., terrified that she was going to burn to death because she was disabled and trapped in our family home on Bennett as five houses immediately surrounding her had all been torched at once.

I attempted to drive over and get her out, but she was trapped among fire trucks and police tape that I couldn’t cross to get to her. When I finally was allowed through just before dawn the next morning, we cried on her back porch as the sun came up over the ash that covered her patio furniture like so much fresh fallen snow.

That morning she finally decided to let us move her to Flushing, ending 30 years of our family’s presence on Bennett Avenue.

Now I do feel safe in this serene little East Village enclave. The strange thing about living in one of Flint’s safe neighborhoods is that the people here think that their Flint is the real one and get irritated when people like me talk about the violence that plagues the rest of the city.

People here often seem to believe that if we ignore the violence and focus on some development in the downtown, the rest of the city will magically be alleviated of its traumas.

When former mayor Dayne Walling, who grew up in the Village, expresses shock at the Flint water crisis, it strikes me as amusing because this clearly isn’t the first time the government has failed us at every level and allowed us to descend into a lethal public health crisis.

How could we have trusted government professionals to keep us safe? They haven’t in most of the city for all of my life. I doubt people who’ve grown up in neighborhoods like the one I grew up in share that level of faith in the assurances of our government over the experiences of our neighbors.

So sometimes I feel more like an interloper than villager, but I do feel safe here, too, and recognize how complacency can set in when we can afford to isolate ourselves from the broader experiences of city life.

On Halloween, when kids from all over Flint flock to trick-or-treat in the safety of the East Village, I’ll welcome them with enthusiasm and pricey chocolates and hope they get to experience a magical evening of only imaginary horrors.

I’m lucky to have lived 10 years here without having any tragedies at close quarters, while all over the city, among people like me, the real terror continues.

EVM Staff Writer Melodee Mabbitt can be reached at melodee.mabbitt@gmail.com. She will be sharing her work with the publication FlintBeat in the coming weeks, joining a journalism project focused on gun violence.

You must be logged in to post a comment.