By Paul Rozycki

What’s your answer to any of these questions about the COVID-19 crisis?

Should we wear a face mask or not? If so when?

Will the summer heat kill the virus?

Will hydroxychloroquine get rid of it?

Will there be a vaccine by the end of the year?

When should the nation begin to ‘open up’?

When will I be able to get a haircut?

What is an ‘essential service’?

Should I go to my dentist or doctor for routine exams?

When will my kids be able to go to school?

Who’s in charge of dealing with the crisis? The president? The states? Every local official? Medical experts?

In the end, who should I trust?

If you answered any of those questions, or a hundred others, with a shrug, or ‘Who knows?’ or ‘I haven’t got the slightest idea,’ join the club. At one time or another, we’ve had a variety of conflicting answers to all of those questions from those in charge of leading us through this crisis.

In many ways that may be the most frustrating aspect of this whole COVID-19 crisis. At a time when the nation needs to rely on solid leadership, it’s unclear who is in charge, who we should trust, and what advice we should follow. At every level of government we’ve been blanketed with mixed messages about the COVID virus.

On the national level

The conflicting answers are most obvious on the national level. President Trump’s responses have gone from predicting that it would be a “little touch of the flu,” that would be gone in a few weeks, to realizing that it would be a major medical crisis for the nation. He’s promised to “open up the nation” and encouraged those who protested state shutdowns, at the same time he urged people to wear masks, avoid crowds, and flatten the curve.

He’s suggested that taking some sort of disinfectant might fight the virus, as medical experts, just a few feet away, shook their heads, and later warned about the dangers of internal use of bleach or other disinfectants. The companies that produced the disinfectants felt compelled to issue warnings about taking their product internally.

Within the federal bureaucracy, those who disagreed with Trump’s take on the crisis were either fired, or moved to less visible positions in the administration. He’s said it wasn’t his responsibility, and blamed the Obama administration, the Chinese, the Democrats and others for the problem. He said that the governors were in charge, only to criticize the same governors when they took action. Calling the advice of the administration mixed messages is an understatement.

What about the states?

So the national government has hardly been a stable beacon of wisdom and information. What about the states?

As diverse as they are, they also have given mixed messages. Some states, like New York, Michigan or California have taken a strong “shut down” stand to quell the virus they were facing. Others, often in the south, or the mountain west, did little, and hoped for the best, at least until they faced a surge in their own jurisdictions.

Within the states, the signals were also mixed. Michigan has been a prime example. As Gov. Whitmer moved to implement a strong “shut down” of non-essential activity, she faced challenges from Republican lawmakers, and court challenges over which law would apply to declarations of emergency. A 1945 law gave the governor wide ranging emergency powers while a 1976 law required the governor to get legislative approval for an extended declaration of emergency.

Within the states, the signals were also mixed. Michigan has been a prime example. As Gov. Whitmer moved to implement a strong “shut down” of non-essential activity, she faced challenges from Republican lawmakers, and court challenges over which law would apply to declarations of emergency. A 1945 law gave the governor wide ranging emergency powers while a 1976 law required the governor to get legislative approval for an extended declaration of emergency.

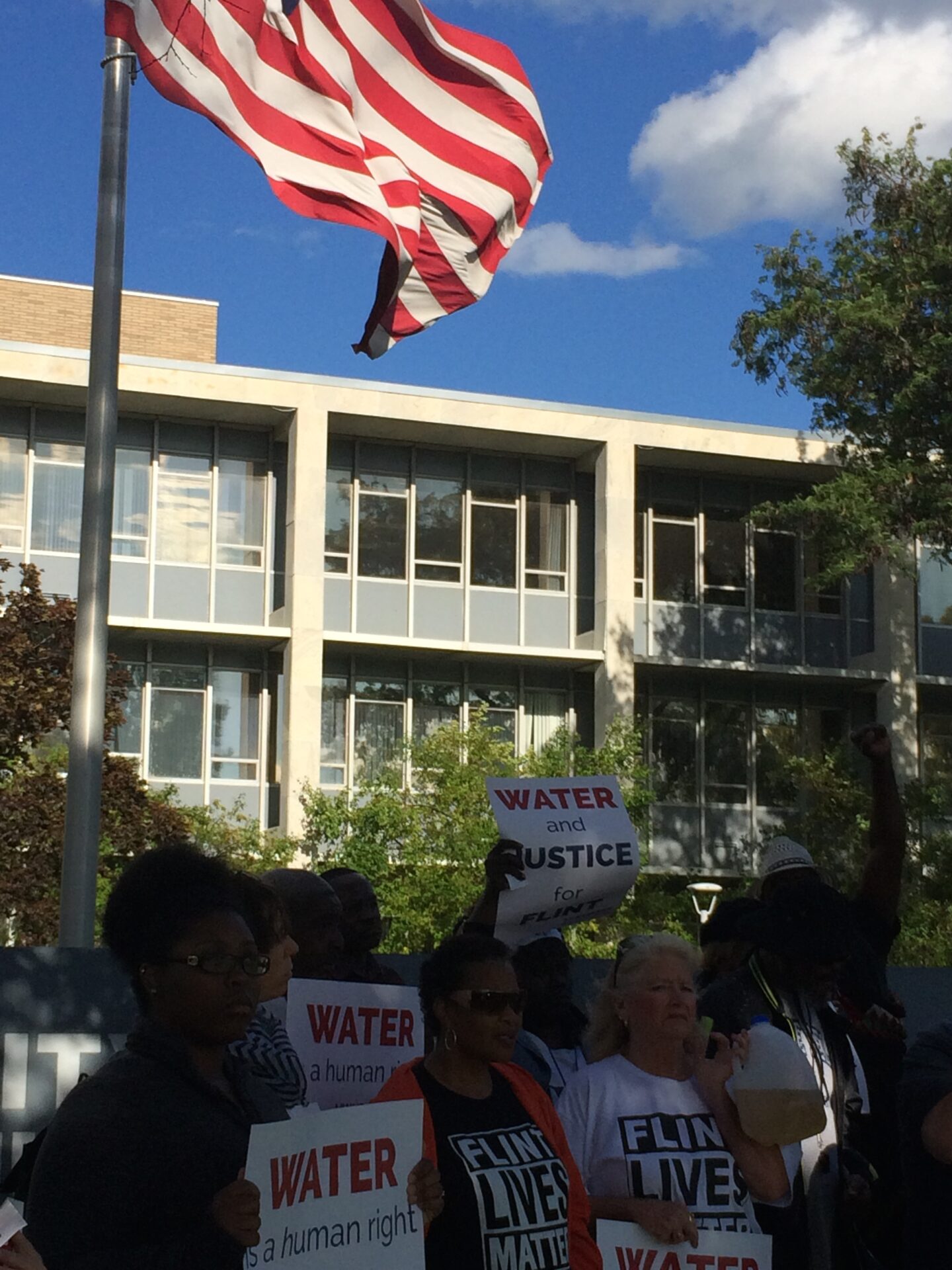

So far, the courts have upheld the governor’s action, but the conflict and challenges continue, and they hardly gave the public a clear message of how they should respond. In addition to the legal challenges, Michigan, and other states, have experienced organized protests in response to shut downs and “stay at home” mandates. While many of them were intended to be peaceful and civil protests, raising serious concerns about business closings and job loss, they were often taken over by armed vigilantes, waving Confederate flags, swastikas, and Trump banners.

Even as Trump said that it was each state’s duty to deal with the crisis, he praised the protestors, and attacked Gov. Whitmer, and other Democratic governors, even as they carried out some of the same policies that his administration advocated.

On the local level

Within the states, on the local level, the mixed messages were just as prevalent. As the governor asks for a state-wide shutdown and requests that we stay at home, some local sheriffs and prosecutors have refused to implement her order. Others, like Flint’s mayor, have gone further and established a curfew.

While most people have generally complied with the shut down and stay at home orders, some have made it a point to violate them as a matter of protest. Owosso barber, Karl Manke, opened his barbershop in defiance of the governor’s order, and generated national attention to his cause. A local judge gave support to his actions, in contrast to most other judicial rulings in the state.

The American public

With all the mixed messages and conflict on the national, state, and local levels, what is the public to think?

If there has been anyone who has been relatively consistent in their views on this crisis it might be the American public. Most polls show that, in spite of all the conflict, protests, and divisive tweets, a strong majority of the public, about 65 or 70 percent, supports a wide-spread shutdown and stay at home policy.

The majority have expressed greater trust in the medical experts, than they do to most political leaders. To be sure, there may be misgivings and frustration about particular details of any policy, but they seem to be well aware of the fact that, as tempting as it might be to ‘open things up,’ a second wave of the COVID-19 virus could be worse than the first, and even more damaging to the economy.

Even those small business owners, who may feel the pain of the shutdown more than most, have divided feelings. Of course, they want to open up and start making a living again, but at what risk to themselves and their customers? Even if they open, how long will it take before the public feels comfortable going to a bar, sitting in a restaurant, or going to a ball game? If they open up too early, could they face financially crippling lawsuits if someone gets ill?

Who should we trust?

To be sure, there are many unknowns with COVID-19. Research is continuing, and there is good reason policies might change as we learn more. And there may be good reasons why there could be different solutions for different areas. But if they want to keep our trust, leaders should be honest and say that.

There has been much lost in the COVID-19 pandemic, and most certainly there will be more losses in the future, both personal and financial. But perhaps the greatest loss is the loss of trust in many governmental institutions that we normally rely on in a time of crisis.

Having lived through the Flint water crisis, we know that the loss of trust can be destroyed all too easily, and it can take longer to rebuild trust than it takes to solve the problem that undermined it. That’s certainly been true of the Flint water crisis, and it may well be true for the COVID-19 crisis.

Paul Rozycki (Photo by Nancy Rozycki)

EVM political commentator Paul Rozycki can be reached at paul.rozycki@mcc.edu.

You must be logged in to post a comment.