By Connor Coyne

On a Sunday at the end of June, my alarm goes off at three in the morning. I dress in the darkness, putting on the loose fitting shirt and shorts I’d selected the night before. I’m careful not to wake my wife who will sleep for several more hours in the antiseptic breeze of our air-conditioned bedroom.

I tap out down the hallway, softly lit by the glow from the bathroom nightlight, past my daughters’ rooms, and down into the kitchen. I eat a hurried breakfast of loco moco; it’s Hawaiian comfort food made from rice, ground beef (I use Spam), egg, and brown gravy. I choose it this morning because the food is loaded with carbs and protein. I allow myself a single shot of black coffee. Our pet rabbit is awake and watches me as I eat, so we make light conversation.

“I’m just eager to get out on the road,” I tell her, and she twitches her nose in reply.

I triple check my backpack for the bottles of water, the sacks of nuts and dried fruit, the sunscreen, the hand sanitizer, and the face mask for the inevitable bathroom breaks.

After decades of short walks, long walks, night walks, and walks during the day, I figure it’s high time I tackle a marathon. I’ve trained, sort of. I’ve obtained my wife’s blessing to be gone for a half day and to return home exhausted. Now, with the air still cool and the stars wheeling overhead, I’m ready to go.

I finally make it out of the house around four. By some measures the day has already begun.

“Astronomical twilight,” or the period when the sun is between twelve and eighteen degrees below the horizon, is the phase of the morning during which brighter stars are dimmed and dimmer stars vanish from the sky. At the height of the summer, astronomical twilight begins around four in Flint, but in the hazy light of the street lamps, the sky is indistinguishable from night.

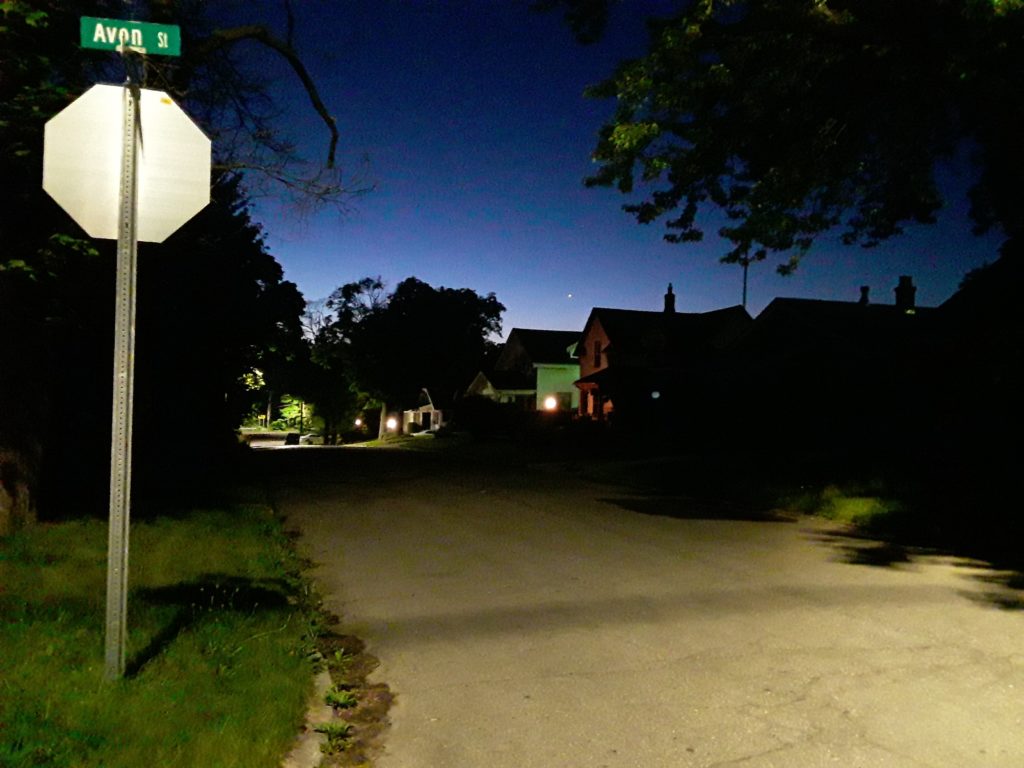

Avon Street in early morning light (Photo by Connor Coyne)

I make my way along Calumet Avenue until I reach Pierce School. I circle through the pitted parking lot of the golf course, and follow the sinewy path of Gilkey Creek as it winds its way northward. I want to cross every bridge at least once, which takes me on a detour up Avon Street, the sky, now discernibly purple, tucked between the darker silhouettes of intervening branches, heavy with leaves. I try to remember when these branches had all been leafless. It hasn’t been that long ago. Two, three months. But time moves both sluggish and fast in the midst of Coronatide, so it is hard to feel one way or the other about the permanence and impermanence of the leaves. I finally reach Court Street. Rejoin the creek at the bike path. Wind my way through Mott College and then Kearsley Park as the sky grows brighter and brighter overhead.

For more than half of my life, walks have been exercise, meditation, and ritual for me. It has been almost a religion. We’re used to movement designed for speed and efficiency. We drive our cars most places, and most of us — me included — drive about as fast as we reasonably can. We might even have occasion to fly across the country, boarding an airplane at dawn in Detroit winter and climbing off in California summer a few hours later, and look, it’s still morning!

Walking is neither fast nor efficient. I can walk across our small town in the same time it takes a 747 to cross four time zones and touch down beneath the Hollywood sign. But walking is also an ancient, low-maintenance form of movement. Look back through history and prehistory, and you’ll find people walking. You’ll find people walking before we were even people, properly speaking. Most of our terrestrial brethren — the wolf and the bear — walk as well. All you need is a pair of feet and the ability to use them.

And… walking is intimate. Even when I take a more routine walk through the neighborhood — a time-worn circuit down Second and Tuscola and Commonwealth that carries me past my little childhood home — I have ample time to notice each house. What has changed there? Is the lawn a little wild? Is there a chalk drawing of a hopscotch court? Who has a graduation banner up this year? Who has replaced their dusty impatiens with a single lacy hollyhock? Who lives in these houses, and what are they living right now? These are the things you get to notice on a walk.

The walking app on my phone doesn’t indicate that I am walking any faster as the morning wears on, but time nevertheless seems to flow more easily, smoothly and without interruption. I reach Hamilton and cross the river. I finish a bottle of water and discover an immaculate Porta Potty in Vietnam Veterans’ Park. It’s a perpetually serene and empty space at the geographic center of Flint. Then I make my way along the Flint River Trail as the sun rises over our namesake, and sit down near the slipway — I’ve already forgotten the roar of the Hamilton Dam — and text my wife to let her know I’ve made it to dawn. It is now six a.m. and I have walked six miles. I have more than twenty to go.

I still remember the first time I realized the latent spiritual power of a walk. I was seventeen and spending a night at a friend’s threadbare house on Flushing Road, right where the city dissolves into a twilight of suburban space, crabgrass, and unpaved roads. It was 1996. I had just endured an embarrassing breakup, and my friend had just been beaten senseless in a darkened hallway of his high school. As we both worried about our recent injuries, physical and psychic, a storm built beyond those thin walls and the rain finally broke. It was June first. It was four a.m. We’d both had enough. We had to get out. We had to use something that belonged exclusively to us. Our legs.

I remember we walked a mile into town, because the 7-11 at the corner of Chevrolet and Flushing was selling Super Big Gulp pops and slushies for sixty-nine cents. From there we made our way down to the river, got lost in Mott Park, and somehow worked our way back to his house by six. We got in before his mom woke up and was any the wiser. (Well, that’s what we thought. She later told him she knew all about our late-night wanderings.)

Early morning fog in Kearsley Parks (Photo by Connor Coyne)

Today, I cross the river every chance I get, trying to tack miles on to my total. I catch myself slowing down as I stroll the Eden of Chevy Commons, not in any rush to leave the symphony of summer fragrance that blossoms out in the heat of the climbing sun. I take the Genesee County Trail right out to city limits where I find a single, masked waitress presiding over the bathrooms at Dom’s Diner. Then, out on the same goldenrod trail all the way to Linden Road, where I have to stumble across parking lots and grassy medians bereft of sidewalk. I turn onto Miller Road and start heading east again. Somewhere before Lennon Road, I hit the halfway point.

Throughout my senior year of high school, my friend and I took many walks, always in the depths of night, expanding our horizons on each journey. The night challenged our senses, wakening our awareness of smell and hearing, while our eyes tried to tease the secrets from each shadow. After a year passed, we’d run through sprinklers at Chuck E. Cheese, raced shopping carts in the barren parking lot of the Corunna Road Kroger’s, and witnessed a lonely McDonald’s custodian dancing across the tiled floor with a yellow mop as his partner.

I left for college in Chicago that fall, and by then I was addicted to walking. My feet comforted me when I was lost. But my friend had to stay behind in Michigan, so I learned to walk on my own. I’d spend entire nights walking, starting in Downtown Chicago and striding north until the suburban condos of Evanston climbed up out of gray Lake Michigan, or south to Hyde Park where the mist gathered thick in the middle of the sunken Midway Plaisance.

Later, when I lived in New York, my new wife and I walked across the Manhattan Bridge in the middle of the night, grabbed submarine sandwiches, twined our way through the human smells and greasy slick of the Lower East Side, the steam rising off of Chinatown sidewalks, and followed the legendary Brooklyn Bridge back home.

Once, when I lived on the Eastside of Flint – Maryland and Iowa – I spent a night walking the entire perimeter of the Flint’s city limits, making friends as I went. That was longer than a marathon by several miles, but I was young and dumb.

But I also took quick walks, modest walks, daytime walks, from my parents’ near the quad-levels outside Flushing to my grandmother’s old farmhouse in that city. Those walks, three or four miles at most, were the longest of all, because they carried me decades back in time to a world full of sparklers and watermelon seeds, and running through the sprinkler while a dozen aunts and uncles laughed, all of them long gone now.

By such a metric, maybe today’s walk is the prosaic one! I’ve simply never done a capital “M” Marathon walk before. I’ve never walked so far simply for the sake of walking so far. And now that I’m getting a bit older, my legs cramping more easily, headaches coming on almost every day, more cynical and sentimental at the same time, I want to prove to myself that I can still do this.

Flint River and downtown Flint (Photo by Connor Coyne)

In the miniature epic that is my Marathon Walk, Miller Road, its expressways and traffic and noise and heat, feels like the whole world. These are the shores from which Greater Flint embarks toward Paris and Pakistan and Argentina and Angola. Each surge of vehicles that sweeps past me toward the interstate is a clutch of questions and adventures. I turn away from it all at Austins Parkway, where a chrome diner and a Harley dealership give way to the low-slung motels and hotels, all of them rife with their own stories and adventures. I twist through unpaved roads and pedestrian overpasses until I’m back at Graham Road. I pass a Catholic school that is somehow closing and a movie theater that is somehow still open. I break against Beecher Road, flow downstream into Flint at McLaren, and enjoy the wetlands and the shaggy grass at the Mott Park recreational area. Some disc golfers stare at me. I probably look way too sunburned and shaggy for an hour or two tossing Frisbee. Hey, what time is it anyway? The light is too bright to read the screen on my phone. By now my feet are starting to hurt. Surely I’m almost done. Right?

Nope. I’m at twenty miles. Six more to go.

So I take the Flint River Trail past Atwood and through Carriage Town as the morning shifts toward the afternoon, and I’m sweating buckets now and my feet are telling me to just rest for a minute. But if I rest for a minute I’m pretty sure I’ll be calling my wife to come and pick me up.

When I get downtown, I rack up more miles by zigging and zagging between the river and Court Street. Beach, Buckham Alley, Saginaw, Brush Alley, and Harrison. Each pass brings me a bit closer to home. People are out on the sidewalks today. They are enjoying their Sunday brunches, after church presumably.

“You can do it, Connor!” I imagine them cheering. “You’ve been walking for eight hours and you’re almost done!”

“Put your masks on, fools!” I imagine myself shouting back.

And then I’ve left downtown. I’m passing through the Cultural Center, and its gorgeous oak trees seem to be telling me that they’ve got much more stamina than I do. The new facades at the public library and Sloan Museum seem to be telling me that I’m not young like they are. Nope, I’ve crossed the threshold of forty over a year ago. Officially over the hill.

“Whatever,” I tell them. “I’m walking a marathon today, and I’m going to finish it, dammit.”

From there it’s a short but interminable pass through Mott College and past the brass monstrosity of the armillary sphere. (An armillary sphere is literally a model of everything in the universe, being a model of the sky, and nothing makes the universe seem so large as trying to walk across 26.2 miles of it in a single day.) Court Street is all dug up, its chipped asphalt baking in the soaring sun. I know how it feels. I’m sweating and gross as I enter the last block of my walk. My feet and thighs are fighting over who feels worse. The leaves wear their green like they’re already tired from a long hot summer, but summer’s only just begun.

Whatever. I’ve done it. I’m stumbling up the driveway. I’m lifting my feet up those final few steps. I’m pulling open the screen back door.

I step inside.

My daughters are watching TV.

The rabbit is lounging in the kitchen exactly where I left her.

The air is cool and breezy and dark. Everything that the air outside is not.

“Hi guys,” I say. “I’m home.”

Banner photo of downtown from Chevy Commons by Connor Coyne.

Flint-based writer Connor Coyne is the author of several books, the latest being Urbantasm: The Empty Room, part two of his young adult serial allegory (reviewed here by EVM’s Robert Thomas) and is the founder and publisher of Gothic Funk Press. He lives in the College Cultural neighborhood with his wife Jessica, daughters Mary and Ruby, and a pet rabbit. More information about him and his work is available at connor coyne.com.

Connor Coyne near the end of his 26-mile Flint walk (Selfie)

You must be logged in to post a comment.