By Harold C. Ford

“On a daily basis, every moment, black folks are being bombarded with images of our death and after a while that does something to your psyche. It’s literally saying, ‘Black people, you might be next. You will be next.’ ” …Matthew Wead, artist

The black and white woodcut prints of Matthew Wead’s Black Matters collection focus on tragedy: grim images of black and brown victims of police violence in the moments before their lives are snuffed out.

However, the most tragic aspect of Wead’s work may be the inexorable body count that affords the artist an opportunity to add to his collection. In fact, the images of three more victims—George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery—were added since the exhibit’s installation at the Flint Institute of Arts (FIA) on July 6, 2020.

Although the initial series, titled “Shooting Targets”, was completed in 2009, Wead said it “has now become a never-ending and daunting task.”

Origins of Black Matters:

Wead, a graduate of Morehouse College (BFA, 2006) and the University of Maryland (2009), was moved toward Shooting Targets and Black Matters by the brutal 2006 arrest of Mostafa Tabatabainejad, a UCLA student. Tabatabainejad, an Iranian-American, was drive stunned five times with a Taser while handcuffed. His offense? He declined to show his UCLA ID card because he thought he was being racially profiled.

The screams of Tabatabainejad troubled Wead. “I couldn’t get it out of my head for a couple of days,” he recalled during a remote interview with FIA patrons on Aug. 19. “It was very visceral…he was in pain.”

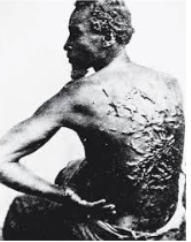

The Tasing of Tabatabainejad reminded Wead of the all-too-familiar photograph of “Whipped Peter” published in Harper’s Weekly in July 1863. Whipped Peter, actual name Gordon, turned his back to the camera to show the horrible scars from a savage whipping by a slave master.

“Whipped Peter” (actual name Gordon)

Image first appeared in Harper’s Weekly, 1863

This image from Deadline.com

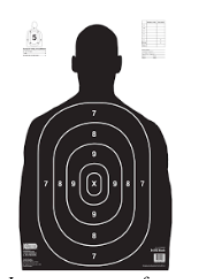

Police shootings sent Wead to a gun shooting range to experience the firing of a weapon. Eerily, the targets at the shooting range were black silhouettes on a white paper.

“It was emotionally impactful for me,” said Wead. “I’ve had guns put in my face.”

Thus, the inspiration for the earlier Shooting Targets and the present Black Matters was born.

Image source: gunfun.com

Artistic influences:

During the Aug. 19 interview with the FIA’s Tracee Glab, curator of collections and exhibitions, Wead revealed that his artistic style was influenced by Caravaggio, Robert Longo, Elizabeth Catlett, and Kathe Kollwitz.

The Italian artist Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1571-1610, “used ordinary working people with irregular, rough and characterful faces as models…”.

Caravaggio’s “Boy bitten by a Lizard”

Image from the National Gallery of Art

“He’s always dramatic,” said Wead, “plays with shadows, plays with light. He’s one of the artists I admire the most.”

Wead admitted his work has similarities with Longo’s “Men in the Cities” series but noted, “I focus more on the faces.” An American artist, filmmaker, and musician, Longo became well known in the 1980s for his print series that depicted well-dressed persons in contorted emotional expressions.

Untitled, 1980, from Robert Longo’s “Men in the Cities” series

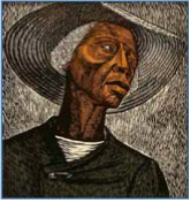

Catlett, 1915-2012, was a graphic artist and sculptor best known for her depictions of the African American experience in the 20th century.

“Her life story is very dramatic,” said Wead. “It’s about the very dramatic.”

“Sharecropper”, 1952, by Elizabeth Catlett

Kollwitz, 1867-1945, was a German painter, sculptor, and printmaker whose artistic themes included poverty, hunger, and war.

Wead was drawn to the “skeleton-like figures” of Kollwitz. “I’m drawn to these dramatic characters,” he said.

“Self-Portrait With Hand on Forehead”, 1910, Kathe Kollwitz, Image source here:

Self-Portrait With Hand on Forehead

Artist as model:

Ronald Madison

The model for Wead’s prints is Wead himself. He imagines what the emotions and appearance of a victim would be in the moments before tragedy. He endeavors to model the posture, facial expression, and emotional state of victims in the seconds before their lives are ended.

Wead’s response to a query about self-modeling: “practicality.” It’s easier than searching for, securing, and paying for models.

There is a price to pay, however, for his approach to making this art. “It was emotionally draining for me,” he confessed. He watched the George Floyd murder video nearly two dozen times to capture the moment that rocked this nation and the world.

Self-photographs of his poses are then artistically parlayed into woodcut prints, an art form he’s practiced since his college days. Printmaking is historically associated with resistance movements, he explained, as it can be done inexpensively.

Nonetheless, the printmaker’s payoff is obscured until the end of the process. “You never know what a woodcut will be until you lift up the print,” said Wead.

Kiehl Coppin

Dreadful repetition:

Visitors to the Black Matters exhibit will learn about victims that are less well known than George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. While the names of the victims vary, and some of the details differ, the storylines are strikingly similar. A few examples from the exhibit:

Ronald Madison: Madison’s life ended on Sept. 4, 2005, less than a week after Hurricane Katrina slammed into New Orleans. The police claimed that Madison was reaching for a gun. An autopsy revealed no gunpowder residue on Madison’s hands and five gunshot wounds in the back. Madison’s brother testified a group of nearby teens were responsible for the shooting and said he and his brother were unarmed. Six years later, five of the seven officers were convicted; those convictions were later vacated, new trials were ordered, and the initial sentences were reduced.

Khiel Coppin: Coppin, an 18-year-old mentally ill man, died on Nov. 12, 2007 when five New York City police officers fired 20 bullets at him. The officers were responding to a call from Coppin’s mother who reported that he’d stopped taking his antipsychotic medicine and had earlier brandished a knife inside the family’s apartment. When Coppin, outside the apartment, reached inside his sweatshirt, the officers opened fire. Coppin was reaching for a hairbrush.

Matthew Wead, American, born 1984. Ronald Madison, 2009. Woodcut on paper, 36 × 24 in. (91.4 × 61 cm) Image: 36 × 24 in. (91.4 × 61 cm). Museum purchase 2009.96

Matthew Wead

https://flintarts.org/events/exhibitions/black-matters

Exhibit open through Oct. 11:

The Black Matters exhibit is at the Flint Institute of Arts (FIA) through Oct. 11: Mon-Fri, 10a-5p; Sat, 10 a.m.-5 p.m.; Sun, 1-5 p.m. The FIA is operating under guidelines from Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, MIOSHA, OSHA, and the CDC. The FIA has added supplemental precautions including enhanced cleanings and a new air filtration system.

EVM Staff Writer Harold C. Ford can be reached at hcford1185@gmail.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.