By Jan Worth-Nelson

At a back corner table at Churchhill’s, escaping to AC on a muggy Tuesday afternoon in Flint, Ben Hamper takes a swig of his signature Jim Beam and Diet Coke and reflects on the 30 years since the country came to know him as an exuberantly profane, honest and hilariously irreverent blue collar bard.

He was The Rivethead.

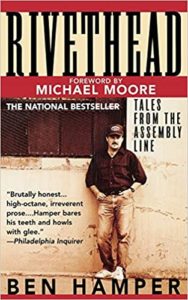

The 1991 book cover

His 1991 book Rivethead: Tales from the Assembly Line, is a raucous, scathing and sometimes heart-wrenching account of his almost ten years in the 80s as a General Motors “shop rat,” at Chevy Truck and Bus. The book was a surprise best seller, and the resultant hullaballoo around it changed Hamper’s life.

Hamper, now pushing 66 and a longtime resident of Sutton’s Bay, was recently featured at a book signing at Totem Books in observance of Rivethead’s 30th anniversary. His mother and many relatives still live in Flint.

Spinning off initially from his relationship with Flint’s other ‘80s bad boy, Davison native and filmmaker Michael Moore, Hamper put Flint on the map yet again as the birthplace not just of its cars and catastrophes, but a fertile ground for startling assembly-line anarchy and bitter dark humor about working class life at the tail end of the GM boom times.

“The factories weren’t looking for a few good men,” he writes in the book’s opening chapter. “They were dragging the lagoon for optionless bumpkins with brats to feed and livers to bathe. An educated man might hang on for a while, but was apt to flee at any given whistle. That wasn’t any good for corporate continuity. GM wanted the salt of the earth, dung-heavers, flunkies and leeches—men who would grunt the day away void of self-betterment, numbed out cyborgs willing to swap cerebellum loaf for patio furniture, a second jalopy and a tragic carpet ride deboarding curbside in front of some pseudo-Tudor dollhouse on the outskirts of town.”

The national media of the 1990s couldn’t get enough of Hamper’s story.

The book was reviewed in dozens of publications, from Fortune Magazine to the Christian Science Monitor to the Village Voice. He was called ‘the blue collar Tom Wolfe,” and “as corrosively funny as a whoopee cushion filled with acid.” He was compared to the poet Charles Bukowski and hailed as a new talent emerging from the working class.

He was on the cover of the Wall Street Journal; his writing was picked up by Harper’s and the Detroit Free Press; and he did appearances on radio and TV around the country from east to west.

Within a month of the book’s publication, Hamper signed a contract to option it for a movie, receiving a six-figure check, one of several, as prospective director Richard Linklater tried to make it happen. Actor Matt Dillon came to town to scope out Hamper’s favorite haunts and try on the Rivethead persona. But the project never made it.

A 1973 Powers High School graduate who’d spent his whole life in Flint, Hamper was hardly ready for the attention his book attracted.

The whole time, Hamper was wrestling with severe panic attacks, anxieties, agoraphobia, and alcoholism. During his last few years at GM, he was off work for repeated extended periods, some of it spent as an outpatient at a Holly Road mental health clinic, where he was shown playing basketball in Michael Moore’s film Roger and Me.

“I wasn’t prepared for it,” he said of his Rivethead notoriety. “To compensate, I doubled medication and drank more. It was touch and go for awhile – I was not doing well. To go on these TV shows and book tours I would stay loaded.

“It should have been a pretty joyous time in my life, but I don’t remember most of it,” he says.

His portrayal captured shop rats on the sweaty, loud rivet line at Chevy Truck and Bus on Van Slyke Road as subsisting on booze secreted in barrels and car parts, “doubling up” on jobs so that they could cover for each other while the other took off to Mark’s Lounge across the Street or simply imbibe 40-oz brews in the parking lot – Hamper’s Camaro, for example.

He and his fellow shop rats, fighting boredom and repetitive tasks, incorrigibly staged pranks, made up endless games like Rivet Hockey and Dumpster Ball, driving foremen crazy, drawing strings of penalties, threats of firing and unceasing interventions by union reps.

The hijinks come across vividly as acts of resistance and a way of adapting to an onerous situation, the ludicrous infantilizations of management strategies, and the tyranny of the clock.

Contrary to preconceived notions about him, Hamper said he actually liked working on the line, at least at first — adding he was relieved and felt lucky to get in on the last waves of GM factory hires in the late 70s. Having been barely employed and as a struggling husband and father of a small child, Hamper said the good pay meant that he could relax and support his family. He says he figured out how to make it work—it was a realm designed for people who didn’t want to think, underachievers who would just show up and do what they were told.

“In some ways, it was like being paid to flunk high school,” he recalls. “You could horse around, and instead of a teacher, you had a foreman. I got into the flow of it.”

Eventually, though, it began to bother him that his forefathers, his grandfather, his father and uncles, worked for many years in the shop but had nothing to show for it. For Hamper, the chance to write about his rivet line experiences gave him a purpose, a goal, something beyond the boredom, repetitiveness and physical demands.

And Michael Moore fortuituously provided him just the outlet for all that scribing. “It was so enriching,” he says.

“Without Michael Moore, there would have been no Rivethead,” Hamper notes. Moore was “hugely supportive.”

Hamper, whose first love is music, sent a music review to Moore in 1981, and Moore not only ran it in the Flint Voice, Moore’s “underground” magazine of the time, but lured Hamper into writing regular features – at first about music, but eventually describing life on the line. Hamper’s columns quickly became the most popular page in the magazine, eventually forming the heart of the book.

Rivethead included a foreward by Moore – who never worked in the shop himself — and was blurbed by one of Hamper’s literary idols, the late novelist and poet Jim Harrison.

Placing the factory narrative in a heart-wrenching sociological and emotional context, the book also described Hamper’s childhood as the oldest of eight children in a Catholic family with a devout mother and shiftless, flamboyantly alcoholic father who worked briefly in the factory but didn’t last, shifting from job to job and disappearing for days, weeks, and sometimes months at a time.

“He worked at probably every factory in Flint – back then you could get fired at one plant and go across the street to another one and nobody would ask any questions,” Hamper says. “He was a railroad man, car salesman, everything.

“I was really angry at the time I was writing the book,” Hamper says of the searing depictions of his family, sharing cramped space in a three-bedroom house at the corner of Dayton and Lawndale streets in Civic Park. As the oldest kid, Hamper took over for the often-missing dad, doing much of the cooking and childcare while his mother Barbara, a devout Catholic, held down two jobs.

“My mother, she just loved kids and loved us and was totally dedicated to compensating for my dad,” he says.

Rivethead author Ben Hamper in June with his mother, Barbara Goodhue, at the Totem book signing. (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

When his dad read the book, he said, “Why’d you have to tear me an a**hole so big?” but admitted it was true. Eventually his father got sober and Hamper said their relationship was good the last few years of his life. He died in 2005.

“I truly did love him,” Hamper asserts. “He had moments when he was very good, instilled my love of baseball and music.” Both parents were voracious readers and passed the love of reading to Hamper. The family lived a block from the Civic Park library, and Hamper went there every week, sometimes bringing back books for his dad – war stories, his favorites.

While many “shop rats” who read Hamper’s column and later the book affirmed he hit the nail on the head, Hamper’s portrayal did not please everyone. Once he was physically threatened on the line itself by another shop rat who took exception to his less than flattering characterization of deer hunters.

Once on a radio talk show, conservative host Michael Reagan (the late president’s son) reamed Hamper for admitting to the rowdy behavior. A caller angrily piled it on, saying he had problems with his GM car, and when it was investigated the mechanic found an empty vodka bottle in the engine.

“That wasn’t me,” Hamper says he cracked to Reagan. “I drink bourbon.”

But throughout all his years on the rivet line, Hamper maintains, the shop rats produced quality cars. Though there was copious consumption of booze and drugs on breaks and lunch, Hamper says if a worker couldn’t keep the work flow going, everything else fell apart.

Hamper followed Moore from what had become the Michigan Voice to Mother Jones Magazine in the Bay Area, garnering them both even more national attention — and then, as Moore got fired after only his third issue, the publisher complained that one of Hamper’s columns was “tasteless” and “offensive.”

“Since when does tastelessness preclude good writing?” Hamper wrote that he grumbled. “I swear they oughta change the name of that rag to Mother Teresa. I say screw ‘em” — and he followed Moore right back to Michigan.

Nonetheless, Hamper says he cringes now at some of the language he used in the book — the “really sexist stuff” in particular, he says.

“Maybe I was trying to ham it up,” he said, “but it’s just cro-mag frat boy stuff… it’s just too knuckle-dragging, and I don’t like the way it sounds,” he says.

What does he think about General Motors today? Hamper says he doesn’t think about it “one iota” – and he didn’t much when he wrote the book, either.

“I was just dealing with what I saw every day – it’s the story of one guy in one department, 40 people on the rivet line– and the clock. The clock was our enemy.”

‘Writing never was easy for me, and that’s one reason it was easy for me to give it up. I’m really a perfectionist. I would observe these things, that’s heavy, that’s funny, that’s sad, I would keep a pad in my pocket.”

When he got home, often half-drunk, he fleshed out his notes on his mother’s old Underwood electric typewriter, and then when he got up in the morning, when he was sober he would refine what he’d written. A three-step process, day after day.

Sometimes it was one paragraph…it was like a jigsaw puzzle, he says.

Just as we’re into the third round, Hamper’s daughter Sonya joins us at the table after her job at Steady Eddy’s Café at the Farmer’s Market. She is his only child, born to his first wife Joanie when they were only 17.

“So she won’t be self-conscious,” Hamper ducks out to smoke a Marlboro 100 on the street.

The book came out when she was a teenager – she didn’t read it then, but did later, as an adult. She says it was exciting when national attention came his way. She was, and is, proud of the book, proud of his success, and proud of him.

“He was a perfect father,” she says. “He was only 17 when I was born but he never missed a weekend, never missed my birthday; he and my mom never said a bad word about each other to me. I think he wanted to do better than his father did.”

At almost 66, Hamper says he is happy living alone with his cat Haddie, after two divorces, in a house Rivetheadproceeds helped buy years ago in Sutton’s Bay. He’s a grandpa with five grandchildren – Sonya’s kids — three of whom, now of legal drinking age, he notes, incredulous, he took to the White Horse during his Totem Books appearance. On the way out, he carted four coneys to go—a Flint specialty in short supply in Sutton’s Bay.

Hamper says he and Moore are not close now – they last played golf about a dozen years ago, Hamper says, with Moore mostly living in New York City and Hamper satisfied to be mostly anonymous in Sutton’s Bay.

“I want to stress that I’m fine talking about Rivethead,” Hamper says as he finishes his last Jim Beam, “but I am still doing things that aren’t Rivethead – I’m comfortable with that – I like to think about the present.”

He has a part-time job as a dishwasher/prep cook at Sutton Bay’s Village Inn.

“I really enjoy it,” he says. “In so many ways it has the feel of the assembly line, just being one of the guys – I’m the oldest guy in the whole place. Just being off by yourself…I’ve always liked mindless labor, blue collar work, just being off by yourself when you can think your own thoughts.”

He also spends much of his time planning his two radio shows on WNMC -FM, 90.7 in Traverse City – indulging in music, one of his great loves.

One, on the air 8-10 p.m. Fridays, is called Soul Possession. It started out as soul and funk but now features obscure rock ‘n roll. The other, Head for the Hills, is on the air 10 a.m. to noon Sundays,. It’s described as “a two-hour-long exploration of American country music, mainly focusing on the hillbilly and honky tonk genres of the ’50s & ’60s – it features Ernest Tubb, Wanda Jackson, Webb Pierce, Louvin Brothers, Kitty Wells, Del Reeves, Skeets McDonald, Connie Smith, Hank Thompson, Eddie Noack, Maddox Brothers & Rose, Wynn Stewart.”

(When he still lived in Flint Hamper’s late night show Take No Prisoners which ran 1981-1991 on the long-gone public radio station WFBE was wildly popular among certain music geeks and late night drunks and insomniacs.)

“Being a disc jockey, being a radio host, was always my true love,” Hamper says, “And I’ve grown to love other genres along the way. I take so much joy out of that. “

It’s a quiet life, and there will be no more books, he says.

“Rivethead is a story about the factory—it’s not the only story, it’s one story. one guy and one department. That was the story I wanted to tell and was inspired to tell. If that’s my legacy, that one book, that’s fine.”

His last day at GM was April 7, 1988. If he would have stayed, if he had survived all the plant closing and layoffs and replacements by robots, he’d have retired in 2007. He can’t imagine what that would have been like.

As he left the factory for the last time, he writes in the Rivethead epilogue, “I drive away feeling lucky, or something like it.”

“Rivethead was part of my job description – it went hand in hand with when I worked in the factory. So when I quit Rivethead I effectively quit writing… I never believed in writing for the sake of writing. I gotta feel something.”

“I am happy without writing,” he says. “I don’t even think about it. When I wrote I was a writer, and when I don’t write, I’m not a writer.”

“I’m probably more content than at any other point in my life,” Hamper says. “Once you get to a certain age, you just don’t care about a lot of things. It’s a glorious apathy.”

EVM Consulting Editor Jan Worth-Nelson can be reached at janworth1118@gmail.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.