Book review: Persona, place, and poetics in Sarah Carson’s “How to Baptize a Child in Flint, Michigan”

By William Barillas

Born and bred, as the expression goes, in Flint, Michigan, poet Sarah Carson has previously published three chapbooks and two full-length books. The provocatively titled book Poems in Which You Die (2014) consists of surrealistic prose poems, narratives for the most part, that provoke speculation on what mundane yet consequential situations they might symbolize. Perhaps they represent the psychic backdrop to the realism and naturalism of Buick City (2015), with its vignettes and character portraits of postindustrial working-class life in contemporary Flint. The first sentence of “Perfectly Useful Front Lawns” suggests as much: “We live now in a dream between who we are and what scares us.”

That poem, like so many in Carson’s second book, opens into an actual territory where roads not only take us through the present or toward the future but also into the past, as we “follow Chevrolet Avenue across where the river used to be” and “tell passersby how there used to be hockey and how there used to be baseball, that our uncles had lived by radio.” A persona emerges, a version of the poet, and a distinctive milieu: trailer homes, jobs at Walgreens, Walmart, and Meijer, the demolition derby, laundromat, cigarettes, and Mountain Dew. That persona and milieu, as well as Carson’s emerging poetic voice, are both moving and interesting.

Carson’s third book, however, is something else, something more. She had me from the title, and not just because I’m a Flint expatriate and a scholar of Midwestern literature, especially writing from Michigan and, even more specifically, from the Saginaw Valley. It’s the sense of purpose, or rather, method, expressed in the title that I find so apt and so evocative. How does one baptize a child in Flint, Michigan? The phrase suggests a process analysis essay written for a high school or college composition class. Remember those? They trace a sequence of steps, a series of actions toward a particular end, in this case, baptizing a child in Flint, Michigan. How is that done? How does one nurture life and honor the sacred, when one’s place on earth has been disrespected, defiled even?

Cover of How to Baptize a Child in Flint, Michigan Poems by Sarah Carson.

Baptism involves water as a symbol of purity and renewal, a bitter irony for a city whose water was poisoned, whether through sins or crimes of omission or commission by representatives of the state. As Michigan’s greatest poet, Theodore Roethke of Saginaw, wrote in his notebooks, “[w]e have failed to live up to our geography.” Sarah Carson addresses that failure with ritualistic tenderness and attention: “First, hold the curve / of their head like // packed snow / a struck match, // a field mouse / you catch // with the cup / of your hand.” Roethke would have loved that. I love the next step in the process: “Say they can be anything; / refill their root beer; // tell them, / Yes, // people like us / can be great, too.”

The underlying impulse of these poems is praise—measured praise, clear-eyed and knowing. Not surprisingly, most or perhaps all of the poems in this book are odes, a sort of poem that speaks directly about a person, place, or thing, whether a physical object, living being, or concept, offering praise, however equivocal. A number of poems identify themselves as such in their titles, as with “Ode to Brother’s Best Friend in the Trailer Park,” “Ode to the City That Is Not My City” (about Chicago, perhaps, where Carson lived for a time), and “Ode to Flint, Michigan on December 30, 2014, the 78th Anniversary of the Great Sit-down Strike.” Like Keats, H.D., Neruda, and other past authors of odes, Carson knows through both instinct and instruction that, as Rilke says in Sonnets to Orpheus, “[o]nly in the realm of Praising should Lament / walk, the naiad of the wept-for fountain.” We’re talking Flint, after all, and the poet acknowledges violence (in “Don’t Touch,” we’re told how “one boy jumped another, / opened his temple onto concrete”), injustice, neglect, and danger (in “If the Pontiac Broke Down,” the speaker notes “no justice, / but a broken bottle, // a length of razor wire / beneath the slip & slide”).

Such honest witness contradicts the cant of pitchmen and politicians who would turn our ears and thereby our eyes from the reality of our lives, both the beautiful and the ugly. Good poetry does that for us, and the best urban poets of the last hundred years, among them William Carlos Williams, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Sharon Olds, have known what Carson demonstrates in these poems: that one must look into the human heart and, say, a parking lot, with the same soulfulness and sense of framing.

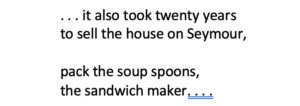

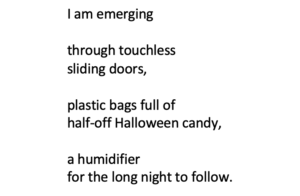

In terms of framing or technique, one notes that most of the poems in this book employ short lines arranged into couplets (stanzas consisting of two lines). This artistic choice provides consistent pacing, rhythm, and a sense of Carson as speaker. Each couplet advances an image, action, or insight, usually as part of a sentence but always with its own unity within a larger flow of syntax and meaning. In poetry, every stanza and every line must work almost as a poem unto itself, and that is the case here. Two passages will illustrate what I mean, both from “Picking up a Prescription for My Daughter at the Rite Aid That Replaced the Rite Aid where My Mother Picked up Prescriptions for Me,” one of my favorite poems in the book, not least because it mentions a road that I know very well:

Then later in the poem:

Taken out of context, these passages naturally lose some of their poignancy and physical immediacy. But their artfulness is still apparent, including the way that line and stanza breaks intensify and even embody meaning. The stanza break after “emerging” is particularly lovely, and the line break after “touchless” perhaps even more so.

This book represents a significant advance for the author both in terms of formal sophistication and engagement with the consensual world of places, people, and experience. How to Baptize a Child in Flint, Michigan represents Carson’s breakthrough, establishing with vivid specificity her personal mythos, her touchstone, her querencia, in the city of her birth. Like Whitman’s Brooklyn, Dickinson’s room and garden, or Roethke’s greenhouses, Flint is the site of her soul’s creation, breaking, and remaking. This is the book Carson will elaborate upon, diverge from, echo, and reinforce in her future writing. It should be recognized as a significant text in contemporary American poetry.

William Barillas is the author of The Midwestern Pastoral: Place and Landscape in Literature of the American Heartland and the editor of A Field Guide to the Poetry of Theodore Roethke. He can be reached at williamdbarillas@gmail.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.