By Paul Rozycki

As the conflict and division over President Trump’s second term grows with his tariff wars, retribution against his opponents, and slashing government programs and personnel, many are turning to next year’s midterm election in the hope that a Democratic majority in the U.S. House could act as a barrier to the worst of his actions.

A shift of only three seats could give the Democrats a majority in the House, and mid-term elections are usually bad news for the party in the Oval Office.

Since 1946, presidents whose popularity was below 50% have lost, on average, 37 seats in the House during midterm elections. Of the 19 midterm elections since that time, the president’s party lost seats in 17 of them and gained seats in only two — 1998 and 2002.

Because so much is at stake in next year’s election, both parties are using every trick in the book to give themselves the edge. In particular, Republicans in Texas are attempting to use one of the oldest election strategies: gerrymandering, or the drawing of election districts to favor a particular party. In an attempt to block the move, Democratic lawmakers briefly left the state, but in the end their move proved unsuccessful.

In response to Texas’ gerrymandering for five more seats, California has threatened to redraw their districts, as well, to give Democrats an advantage. Several other states have indicated that they might take similar action to help one party or the other.

History of gerrymandering

Gerrymandering goes back to the earliest days of the nation, when Elbridge Gerry, vice president of the U.S. and governor of Massachusetts, drew an odd-shaped election district to help his party in 1812. His opponents said it looked like a salamander and therefore called it a “gerrymander.” Over the last two centuries since the term’s coining, both parties have used gerrymandering to gain an advantage.

The legal requirements

It may surprise some to learn that when election districts are drawn, the legal requirements are few.

Based on Supreme Court decisions in the early 1960s, the population of election districts must be equal, so each member of the House speaks for the same number of people. Prior to that time there were wide variations in the number of people in each election district.

Congressional districts are usually redrawn every ten years after the census is taken to adjust for population changes. After the 2020 census there were about 760,000 people in each congressional district, according to a 2021 Library of Congress Report.

Further, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 says that gerrymandering can’t be used to prevent the election of minorities, as was often the case in the old south and elsewhere.

And that’s about it.

So while the law requires that the population of each district be equal, it says little about the shape of those districts and who should create them. That’s where gerrymandering comes in: how the districts are shaped and who draws them can play a major role in determining which party wins or loses.

There are several ways political parties can gain the advantage when drawing election districts.

Packing and cracking

One gerrymandering technique is known as “packing” wherein all the voters of a single party are placed in one district, giving them a huge victory but denying them any significant support in a number of surrounding districts.

A second technique is called “cracking,” wherein all the voters of a single party are divided so they can’t be a majority in any surrounding district.

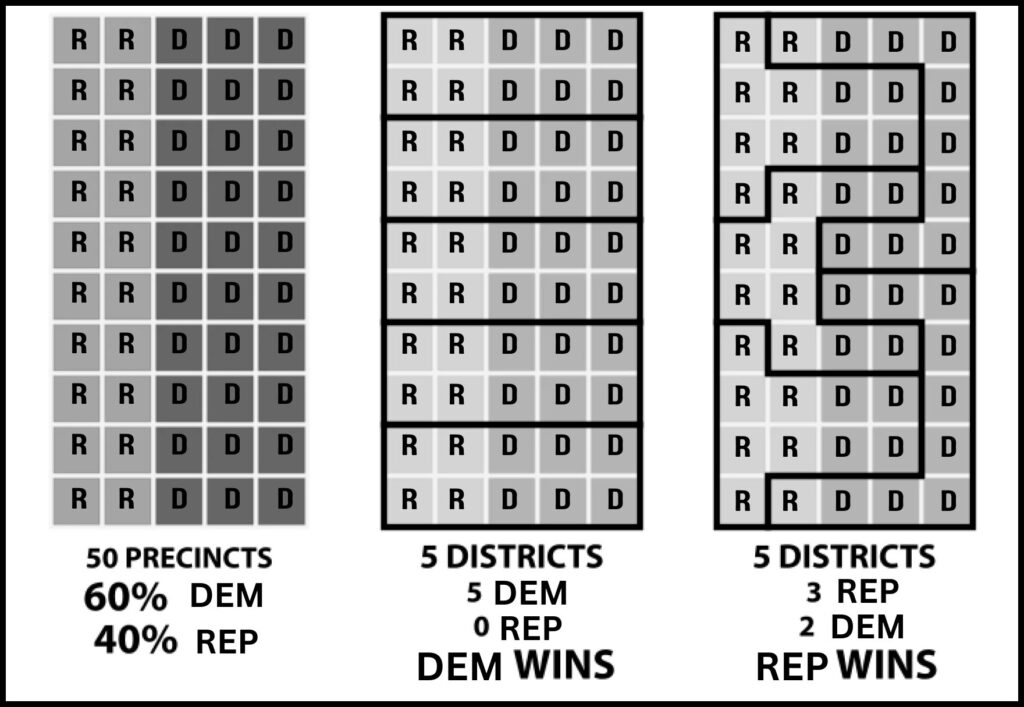

The following charts are examples of how both might work.

In a state with 60% Democrats and 40% Republicans, it’s possible for the Democrats to win all the seats if they “crack” the Republican support, so they don’t have a majority in any district. Similarly it’s possible for the Republicans to win three of the five seats if they “pack” most of the Democrats into two districts.

A few other techniques that are sometimes used are “hijacking,” where two incumbents are placed in the same district assuring that one of them would lose, and “kidnapping” where an incumbent is placed in a new district where they may be little known and have little chance to win.

All of this might be considered inside baseball – of interest only to political junkies – except for the fact that there is so much at stake in the next election.

The implications of gerrymandering

While the current Texas version of midterm gerrymandering is a reflection of the Republicans’ fear that they could lose their razor thin majority in the U.S. House, it’s hardly an exception. Because it’s taking place in the middle of a decade, the current attempts are more blatant than most, over the years both parties have made use of it for their own advantage. For example, in 2022, New York’s Court of Appeals rejected congressional maps that were seen as favoring Democrats, as reported by NBC.

Division, dysfunction, and distrust of democracy

When the selection of members of any elective body is based on gerrymandered districts it leads to at least several major problems.

For starters, it can lead to deeper divisions in Congress.

Today, the great majority of members of Congress are confident of reelection once they are nominated by their party. In 2025, only 40 of the 435 districts were truly competitive according to the Cook Political Report, and gerrymandering is a significant factor in that lack of competitiveness. Thus, the “real” election tends to be the primary, where a candidate only needs to appeal to the activist base of their party.

Often this means that strongly liberal Democrats and strongly conservative Republicans are elected, and both have little motive to work with the other side. Those deep divisions make compromise and policymaking more difficult and may mean that little gets done except attacking the other party—leading to a dysfunctional democracy.

And if democracy can’t function well, it leads to widespread distrust of the whole system and perhaps democracy itself. We’ve seen much of that in recent years. That distrust also tends to manifest a decline in voter participation – because if you don’t trust the system, why vote? Or, in the case of gerrymandering more directly, if you know your party is going to win (or lose) regardless of how many in your party turn out on election day, why bother to vote?

What to do

While gerrymandering isn’t the only cause of our political problems, it’s a significant one. So how can it be solved?

About 13 states, including Michigan, have created Independent Redistricting Commissions, where a non-partisan or bi-partisan commission directs the redrawing of election districts every 10 years. Several other states use various, modified (and perhaps less independent) versions. The results haven’t been perfect, and partisans of both parties are often displeased with the results.

(According to the Harvard Kennedy School, some states like Michigan, California and Arizona have been most successful in creating fair maps with their commissions. Other states, even some with independent commissions, like Ohio or Virginia, have simply continued the problems with gerrymandering.)

While gerrymandering isn’t the only problem we face with our elections, it is a major one, and dealing with it could be a big step forward in restoring trust in our elections and democracy itself.

This article also appears in East Village Magazine’s September 2025 Issue.

You must be logged in to post a comment.