By Teddy Robertson

“Je-zus Christ!” Stress on the first syllable and heavy elongation of the “z” sound. I blurted out one of my father’s favored expletives.

My mother had slammed on the brakes and I tumbled off the bench seat of our old Chevy coupe and hit the floor mat beneath. The brown and red threads of the tan plaid upholstery prickled as I clambered back onto the bench seat.

It was 1951 and I was six years old.

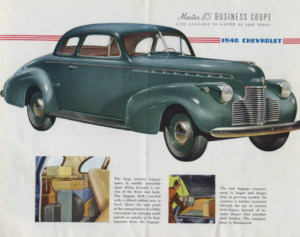

The car was a 1940 Chevrolet, a 2-door business coupe, trim and sporty even with its faded cream finish. A red pin stripe was still visible along its sides. My mother loved that Chevy and decades later I learned why.

(Photo source: www.oldcarbrochures.com)

The day of my startling outburst we were headed into the city—to San Francisco, a 40-minute drive from Mill Valley, our small town north of the Golden Gate Bridge. I watched my mother grip the gearshift with its milky bakelite-tipped handle as she pressed in the clutch in one smooth, deft motion. She was a good driver.

Trips into the city in the 1950s were expeditions that entailed coat, hat and gloves. A deckle-edged Kodak shows me in a gray and white checked coat with a matching tam that my mother had sewed. I wore white gloves in little kid sizes that seem unimaginable now—clothes for city sidewalks, not the gravel roads where we lived.

Our destination was 450 Sutter Street, a medical and dental office building a few blocks uphill from Union Square. At 26-floors and one of the tallest buildings in the city at the time, its art deco entry doors were recessed beneath a gold fan-shaped portico.

(Photo source: www.artsandarchitecture.com)

Waiting for the elevator in the black marble hallway, I craned my neck to look up at the bronze and silver ceiling decorated in Mayan revival motif designs. The dimly lit zig zag shapes made me dizzy. I thought my family dentist lived in a temple on the 16th floor.

For years my mother regaled friends and relatives with the story of precocious mimicry. I cringed, but got used to it.

(Photo source: www.artsandarchitecture-sf.com)

As an only child I lived among adults. My parents had—and now it puzzles me—mostly childless friends, so I listened as grown-ups told stories. But they seemed willing to tell stories on themselves, too. I realized that the best talkers knew how to become a character in a story, become the butt of a good joke.

Kids in grade school never did that.

Grown-ups telling stories—when not at my expense—brought relief from my well-behaved boredom. I watched as the launch of some tale snagged the other conversations scattered about the room, reeled in the attention of highball-clutching adults. I listened to half-understood words about opaque situations: the suspense was exciting. I sensed the drama of any weave or wobble in the story, a gasp of surprise, a sigh of let-down, or a hoot of laughter at the end.

The work of what I later learned to call literary devices seeped into my brain.

Sixty years after I banged into the Chevy dashboard, my mother Virginia came to live with me in Michigan. At age 81 she pulled up stakes on the west coast and moved east to live with me and my son.

Of all places, in Flint.

The back story to the Chevy coupe emerged, this time minus my expletive. Instead, my mother told how she and her older brother Sam had bought the car new in their hometown, Portland, Oregon. In the course of the purchase, the dealer off-handedly mentioned that delivery charges could be saved if the car were picked up at the factory in Michigan.

Brother and kid sister set out east by train. The Great Northern Empire Builder ran daily from Portland to Chicago’s Union Station where they could pick up Grand Trunk Western mainline and get off at Flint. My mother remembered waiting on a gusty Saginaw Street corner for a man who would take them out to the factory—which must have been Chevy-in-the Hole.

The 1957 edition of Great Northern Empire Builder descends from Marias Pass at Bison, Montana. (Photo source: https://www.gnrhs.org/empire_builder.php)

On the drive back to Portland, brother and sister saved money by sharing a motel room; my mother remembered sleeping on a trundle bed. My uncle—a jazz lover—looked for towns along US 30 where he could search record stores.

In 1944, my mother got engaged and planned to move to San Francisco where she would be married. Her brother let her take the car—he was headed to Washington, D.C., to work in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) established by Roosevelt in 1942. Off to a glamorous career in the capital, my uncle readily signed over the title to the Chevy. He threw in the jazz records, heavy 78s in brown paper sleeves, as a wedding present.

The coupe became my parents’ first car.

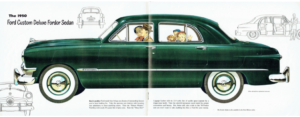

By 1955, my parents needed a newer, more practical family ride. One summer evening my dad pulled into the driveway in a 1950 4-door Ford custom six “executive sedan.” A deep forest green, in the center of its grill a “bullet” jutted out that only underscored the car’s roomy boredom.

(Photo source: www.oldcarbrochures.com)

We never again had a car like that sporty Chevy coupe.

I’m still in Flint. My mother died here in 2008. I learned how to be one of those grown-ups who can tell stories on themselves.

And the Chevrolet Plant Number Four where my mother’s Chevy coupe was likely made? After Delphi demolished the last remaining buildings in 2004, a phased redevelopment restored the resulting brownfield into grasslands, meadows, and woodlands with walking trails. The entire area was re-christened Chevy Commons in 2012. This week (July 14, 2021) Governor Whitmer announced a plan to make the expanse Michigan’s 104th state park.

EVM reporter, Teddy Robinson, can be reached at teddyrob@umich.edu.

You must be logged in to post a comment.