By Jan Worth-Nelson

Note: This story was amended on Feb. 21 to add additional response from Tiffany Brown, public information officer of the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality –Ed.

The city of Flint is far from assuring adequate coverage and information of the water crisis recovery needs of its most vulnerable citizens, many of whom remain deeply distrustful of tap water, have not tested their water for lead, are not confident in their use of filters or don’t have one, and yet still are attempting to follow guidelines for protecting their children and the elderly.

Those are among conclusions released last week from a survey collected in December from more than 2,000 Flint residents. It was created and distributed out of “total fear” for the community, its organizers say, as the State of Michigan seemed to be moving to reduce or withdraw bottled water availability and other supports.

Survey spokeswoman Rev. Monica Villarreal, pastor of Salem Lutheran Church, an activist throughout the water crisis and organizer of the survey project, reviewed results from the 2,029 surveys last week to local media in a report, “From Crisis to Recovery–Household Resources: A Flint Community Survey.”

While testing according to most official reports indicate lead in the city’s water has dropped below federal action levels, many activists insist the crisis is not yet over and warn that pipeline replacement activity and reported difficulties with filter use and lead testing in the community mark the need for continued watchfulness and ongoing state services.

How survey came to be

Villarreal led the survey process which began with the Resource Recovery workgroup and included input and support from the Access and Functional Needs (AFN) service providers and the Communications workgroup of FACT Community Partners. FACT (Flint Action Coordination Team) — also sometimes called Flint Cares — is a coalition of community leaders, activists and residents who came together around the water crisis in late 2015 as the gravity of the situation emerged.

Last Dec. 6, Mayor Karen Weaver released a statement that in a meeting that evening, state officials said they were considering ending bottled water distribution in January, rather than March as had been previously suggested. Villarreal said the statement triggered a series of questions for the MDEQ at the communications group meeting Dec. 7 which subsequently galvanized the community’s response to move forward quickly with the survey.

State officials contend comments made at the meeting with city officials did not represent a decision. Nonetheless, Villarreal said the need to respond to the possibility galvanized her and others to gather information about whether, in fact, the community was moving toward recovery. Ultimately, the January cut-off, which state officials say was not an actual plan, did not occur.

MDEQ responds to survey results

In a phone interview after the release of the survey data, Tiffany Brown, public information officer from the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) said she believed there are some misunderstandings about the state’s intentions and in specific, the role of the CORE program–an element of the state’s services mandated by the 2017 settlement of a lawsuit brought by the Concerned Pastors for Social Action and Flint resident Melissa Mays.

She said the state can document that CORE teams had made contact with a resident at every household in the city of Flint with a water account except roughly 85 households — and CORE workers had gone back repeatedly — an average of over 50 times, she said — to try to connect with that group of 85.

“We can’t force people to get their water tested, or use a filter, but we can educate them. We are continuing our coordinated efforts to get people’s water tested,” Brown said. “I understand that trust has been impacted. I respect the work that the community is doing, but we have to work together to better serve residents and to make sure residents can properly test their water and install filters.”

Regarding the bottled water supply issue, “There has never been a formal announcement that bottled water would stop in January or March,” Brown said. “The state’s position was that we had not made a decision.”

Further, she objected to the suggestion of a perceived withdrawal or threatened withdrawal of state services. In terms of the state’s ongoing support for water crisis recovery, she said, many services are in place. “The state still is providing health care, nutrition programs — many services are continuing,” she said. In a separate email, she wrote, “We remain committed to supporting the city of Flint.”

“I don’t know what the future holds,” Brown said, ” but I can only say that at this point the state has not made an announcement about the availability of bottled water.”

Survey background

Villarreal was joined in the presentation of survey results by Carma Lewis, community outreach coordinator of FACT Community Partners; Jane Richardson, special projects facilitator of the Neighborhood Engagement Hub; and Laura Sullivan, Kettering University professor, a deeply involved water activist.

The one-page, 16-item questionnaire went out during two weeks in late December – with extra days added following a snowstorm.

The questionnaire was targeted to residents likely to be in the most vulnerable categories — those making use of three state-supported programs. Those programs were the four remaining PODs, or point of distribution water supply stations; three HELP Centers– venues for water, food and other assistance funded by the State of Michigan and private funds at three area churches; and the Access and Functional Needs (AFN) programs – those designed for senior citizens, the disabled, and the homebound–basically the most vulnerable dependent families.

Many of the services for residents covered in the survey are outcomes ordered in the March, 2017 U.S. District Court settlement of a lawsuit against the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) by plaintiffs the Concerned Pastors for Social Action and Flint resident Melissa Mays. The plaintiffs were represented by the ACLU and the National Resources Defense Council.

The MDEQ has been implicated in decisions leading to the water crisis, which was triggered by the city’s switch from Lake Huron water to Flint River water when the city was under state-appointed emergency financial manager Darnell Earley in April, 2014. What followed the switch was a trail of improper water treatment, doctored data, the leaching of lead into the city’s water, and the consequent lead poisoning of children and the elderly. So far 15 state and local officials have been indicted in the aftereffects.

Survey demography

Respondents to the survey came from all nine wards of the city.

One third had at least one child under the age of six, one third had a household member over the age of 60. This matters because the medical community has indicated these two populations should be the most careful regarding exposure to lead, recommending that until the risk of lead exposure is fullyresolved in Flint, bottled water is likely the safest choice.

In addition to typical demographic information, the survey asked residents about their quantity and uses of bottle water, lead testing, service lines, their use of filters and what services from the state they believe should be provided.

Key findings:

State support:

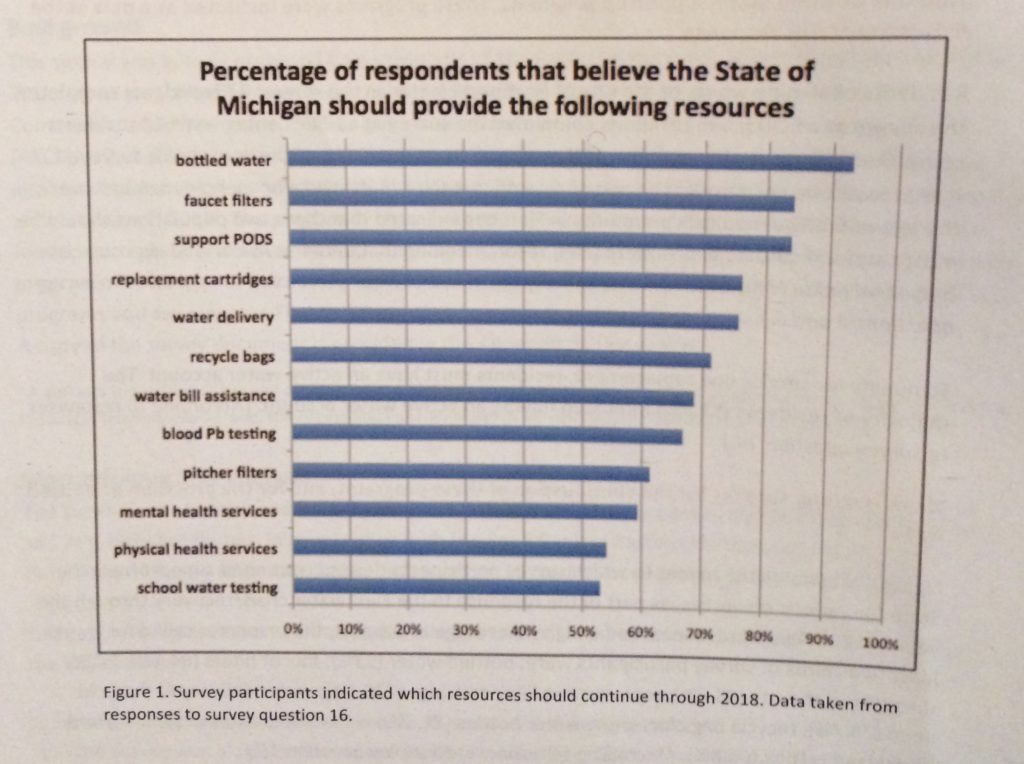

Large majorities of the respondents believe the State of Michigan should continue providing bottled water (93 percent) faucet filters (84 percent) support for the PODs (84 percent) replacement cartridges (76 percent) water delivery (75 percent) water bill assistance (69 percent) and mental and physical health services (59 and 54 percent respectively).

Bottled water use continues:

- 96 percent still use bottled water for cooking, 91 percent for brushing teeth.

- Close to 60 percent use bottled water for bathing, 48 percent for washing hands, 35 percent for pets, 23 percent for baby formula (much higher—48 percent) in homes with babies, obviously) 9 percent for flushing toilets.

- The average household in the survey group uses 14.7 cases of water per week.

Filter use: A significant percentage of respondents (51 percent) either don’t have a water filter installed in their home, or report low confidence in filter use. These answers provide insight, the report asserts, into the effectiveness of the Community Outreach and Education (CORE) program to educate residents on filter use.

Lead testing deficits:

About 40 percent of participants reported never having had their water tested for lead. For more than half the participants, household water had not been tested for lead in the past year. About 39 percent said they did not know how to test their water for lead, and 70 percent said they did not know the composition of their service lines.

“The extent to which residents have their water tested and the frequency of water testing, raise concerns about resident understanding of the importance of water quality monitoring and access to water testing kits,” the report writers concluded. “Lack of knowledge regarding the composition of their own service line is also indicative that residents who participated in the survey have not benefited from programs that would help them understand their level of risk.”

CORE workers, mostly Flint residents hired as part of the lawsuit settlement, have been going door-to-door in the last year with filters, replacement cartridges, and water crisis resource information. If invited in, they are trained to check and install faucet filters.

The data about CORE services should not be interpreted as a failure of the ground-level CORE workers, Villarreal said.

“This is a critique of the program, not the worker. MEDQ failures are systemic,” she said.

“The CORE program is greatly needed,” Villarreal added in an email after the presentation. “With more community input and collaboration, it is hoped that the State of Michigan will create a more effective program design and evaluation process that will improve the outcomes of the CORE Program and ultimately better meet the needs of Flint residents. Until there is no longer any public health risk, the availability of State funded bottled water is necessary.

Tiffany Brown, the MDEQ public information officer, acknowledged she had seen the report and been present for a discussion of it in Flint last week. She stated, “I invited Pastor Monica [Villarreal] for the opportunity to meet with myself and CORE leadership to learn more about the survey and discuss any opportunities to work together to better serve residents.”

Villarreal confirmed the MDEQ has extended an invitation to meet again and that the invite has been accepted.

“We hope for public momentum around it — this is a big deal.,” Villarreal said. “We hope that our state government officials, among others, will use this to better inform programs moving forward.”

Brown said, “Overall, we are very pleased with the work being done by CORE, water quality improvements and progress happening in the city.”

Presented with that statement, Laura Sullivan replied, “Are we to gather that the criteria by which we judge the efficacy of the CORE program is whether or not MDEQ is very pleased with the work? Seriously? Do they not recall the trouble that occurred in 2014 when they responded to resident concerns by saying they were pleased with the situation in Flint?”

Kettering University Professor Laura Sullivan (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

“No entity has asked the people of Flint what they need and then responded with an answer,” Sullivan said. “One reason for the numbers and for the pace and for the request to have this published is to demonstrate to the people of Flint somebody’s listening, somebody’s using the information they provided to try to help them, and isn’t being quiet about it,” she continued. “It’s being as transparent and as open and putting it in as many places as we can.

“Maybe this is a way of trying to build trust in a little piece of Flint,” Sullivan said.

The full report is available here through Flint Neighborhoods United.

Among the total of 2,029 usable surveys returned, a “massive number,” according to Villarreal, many were handwritten, and 56 percent included their contact information—a poignant sign, Villarreal and others asserted, of residents’ strong wish to be known and heard.

“The effects of the water crisis continue to impact the daily lives of Flint residents,” the report states in its conclusion.

“Flint residents are expending extra effort to protect their household from lead exposure. While most residents surveyed have a faucet filter installed, a significant portion of the population surveyed indicated they do not have a faucet filter installed. A reported lack of confidence in using and maintaining faucet filters underscores gaps in the CORE Program and indicates that Flint residents are not sufficiently protected from the potential of large-scale lead releases, particularly as service lines continue to be replaced through 2020” – one of the terms of the March, 2017 lawsuit settlement.

EVM Editor Jan Worth-Nelson can be reached at janworth1118@gmail.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.