By Jan Worth-Nelson

Hurley Medical Center pediatrician Mona Hanna-Attisha, for the past three years regarded as one of the stand-out whistleblowers and heroes of the Flint water crisis, turned the tables on the hometown standing-room-only crowd who came to celebrate her Thursday night.

Hanna-Attisha with Chris Jackson, editor and publisher-in-chief of One World, the Random House imprint that published her book.

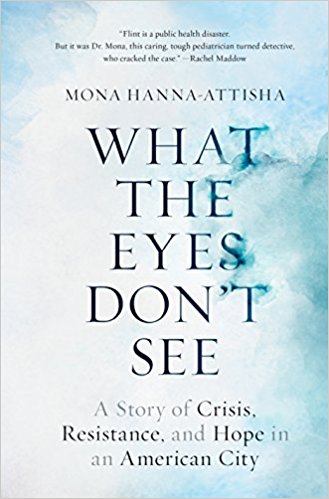

Speaking at the Flint Public Library launch of her book What The Eyes Don’t See: A Story of Crisis, Resistance, and Hope in an American City, Hanna-Attisha said she does not think of herself as a hero, suggesting as a pediatrician, she was simply doing her job. Her findings in collecting and reporting the elevated blood-lead levels of her young Flint patients in 2015, and her insistence that government officials pay attention, blew the crisis open into a national story and disgrace.

However, Hanna-Attisha said, it is the people of Flint who are the “true heroes” of the four-year-old drama. She praised the community for building “a model of hope and recovery” for the whole country. She said the people of Flint have been “brave, stubborn, loud and organized” since the onset of the crisis. She praised the new Educare and Cummings child care centers providing free pre-school for 500 Flint kids, along with Medicaid expansion, Flint Kids Read and newborn literacy programs, nutrition services, the Flint Registry, behavioral services and many other initiatives as evidence the city is making strides.

She noted the remarkable accumulations of the Flint Kids fund through the Community Foundation of Greater Flint, stewards of the more than $18 million donated so far from hundreds of individuals, organizations and corporations around the country in the wake of the crisis. Part of the proceeds from her book, she said, would go into the CFGF fund.

But she also asserted the messages of her book–and lessons from the water crisis– connect directly to a larger crisis of “how we care about children as a whole in our country,” particularly since the last election.

Community Foundation President and CEO Isaiah Oliver and Dr. Lawrence Reynolds, both key figures in the Flint water crisis response. (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

An immigrant to the U.S. at the age of four, Hanna-Attisha described how her parents fled the Iraqi regime of Saddam Hussein and came to America, seeking “freedom, democracy and that American Dream.” She said “Lady Liberty had her arms open and welcomed us.” However, if Donald Trump’s first travel ban had been in force when her parents fled, she said, none of them would have been allowed in.

“Think about what’s happening in this last week,” she said, speaking on the day that President Trump signed an executive order to stop family separations at the border. She said what is happening is “government-sanctioned child abuse… Children are being ripped apart from their parents, children are being traumatized.”

She said she hoped her book would be “a rallying cry to see the power that we have within us — we have to be not only awake and alert, but loud” to effect change.

Hanna-Attisha engaged in conversation from the platform first with State Sen. Jim Ananich and then with Chris Jackson, editor and publisher-in-chief of One World, an imprint of Random House which published her book. Jackson flew in from New York for Hanna-Attisha’s Flint launch.

Saying “this is a book I adore,” Jackson recalled he was grabbed when he heard Hanna-Attisha say her response to the water crisis was a “choiceless choice” because of her ethical, moral and professional obligations. And he noted that in considering recent national events, “there is a unifying thread in some of these things–this indifference to the lives of children.”

Hanna-Attisha further developed the point.

“We are allowing our children to be slaughtered in schools because of inaction on gun violence, we are allowing children to drink poison water here and throughout the nation, we use children’s health insurance as a bargaining chip in Congress, we have one of the highest poverty rates of all industrialized countries,” she said.

She called for “a radical awakening, a radical reckoning to how we are valuing our children.”

She said the deeper she dug into Flint’s story, the more she felt “anger at the officials who were in charge, anger at the loss of democracy, anger at people in charge of the water decisions at the DEQ (Department of Environmental Quality).

There were “clear villains–people that you can name,” she said. But she also came to recognize “the villains that were harder to see–lying underneath–longstanding effects of disinvestment, and poverty and racism and austerity–the undercurrent of this crisis. These are leaving scars that will last forever.”

“These kids literally will be our tomorrows, if we don’t treat them well now, what do we expect about the future of this nation? It is frightening.”

The book’s title, Hanna-Attisha explained. came from a D.H. Lawrence quote, “The eyes don’t see what the mind doesn’t know.” Lead is an invisible poison, she noted, and the only way to track it is to know as much as possible about it, and to follow the science–another theme of her remarks.

Hanna-Attisha signing books for a long line of fans (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

Library director Kay Schwartz thanked Hanna-Attisha for her “stubborn pursuit of the science that made it possible to tell truth to power” in Flint. Hanna-Attisha later said Flint’s recovery requires a basis in science and decried recent trends in the country to deny it.

Pediatric residents in Mona Hanna-Attisha’s program (l-r) Dr. Korie Fudge, Dr. Komal Parmar, Dr. Nadine Peart (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

“Flint was a place where common sense science was denied,” she said, noting that when General Motors stopped using Flint’s water, everybody should have understood there was a problem. And ultimately, she said, science provided the path to recovery.

In summarizing why she wrote the book, Hanna-Attisha said, “I knew that the nation’s attention would fade and move on, as it obviously already has, and I wanted a way to shine a spot light back on Flint.”

“I wanted to very much share the lessons of this crisis, this tragedy, but more important I wanted to share the beauty of Flint,” she said.

“I wanted people to see Flint as I see Flint, as a place of loyal, proud and resilient people, and a place that stood up and said we’ve had enough, and a place that is building an incredible model of hope and recovery, especially for our kids.”

EVM Editor Jan Worth-Nelson can be reached at janworth1118@gmail.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.