By Harold C. Ford

“You are a scoundrel and a skunk…You’ll go to hell when you die if you do things like that.”

–Frances Perkins, U.S. Secretary of Labor, to Alfred Sloan, CEO, General Motors, Jan. 1937

“You can’t talk to me like that…I’ve got seventy million and I made it all myself!”

—General Motors CEO Alfred Sloan’s response to Frances Perkins, U. S. Secretary of Labor, Jan. 1937

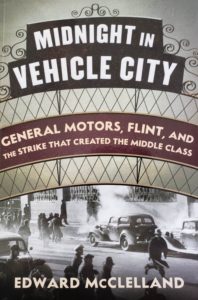

Edward McClelland’s Midnight in Vehicle City, General Motors, Flint, and the Strike that Created the Middle Class brings a fresh look to the seminal moment in Flint’s contribution to American history: the 44-day sit-down strike by autoworkers from Dec. 30, 1936 to Feb. 11, 1937.

The strike ended with an agreement in which General Motors (GM), the world’s largest company, recognized the fledgling United Automobile Workers of America (UAWA) as the exclusive bargaining agent for GM’s approximate half-million laborers.

McClelland writes that “historians have credited [the sit-down strike] as the natal event of the modern American labor movement. The British Broadcasting Corporation dubbed it ‘the strike heard ‘round the world.’”

Simultaneous boom and bust

Flint was at once the most likely and unlikely of places for the great showdown between industry and labor. In the beginning decades of the 20th century, it was the fastest-growing industrial city in the nation. The birthplace of General Motors in 1908, Flint made more cars than any other city in the world, save Detroit.

Tens of thousands were drawn to the Vehicle City by the promise of employment in one of its dozen or so auto factories and multiple supplier businesses. More than 75 percent of Flint’s workforce drew their paychecks from GM or its suppliers.

Nonetheless, GM jobs paid poverty-level wages and were unaccompanied by fringe benefits. Working conditions were often deplorable, unsafe, and unhealthy. Worker rights were nonexistent.

Sit-Down strikers, 1936-37

Photo source: History.com; Bettman Archive/Getty Images

“Not only is the work exhausting, it’s dirty and dangerous,” McClelland writes. “Workers dare not step off the assembly lines, even to use the toilet. There are no fans, no ventilation, no dust masks, no safety glasses.” The conditions were ripe for worker revolt.

The prospects for a successful worker revolt in Flint, however, were unlikely. “In Flint, General Motors was all-powerful and paternalistic,” he writes. GM held sway over state and local politicians, the local press, the police, and the courts. Further, the corporation spent $1 million for Pinkerton detectives to infiltrate and, if necessary, suppress the nascent labor movement with brute force.

“Flint was a GM town to the bone,” observed Victor Reuther, one of three legendary, labor-organizing brothers.

Historical familiarity

The events that unfolded from Dec. 30, 1936 to Feb. 11, 1937 are familiar to many. Flint sit-downers, fed up with the apparent unwillingness of GM to negotiate a contract, took over the Fisher One and Fisher Two plants that made critical components for other factories.

The sit-down fever in Flint spread throughout GM’s industrial kingdom. Work stoppages shut plants in Detroit, Toledo, St. Louis, Oakland, Cleveland, Atlanta, Kansas City, Harrison, N. J., Anderson, Ind., and Janeville, Wis. Half the company’s plants were closed.

Flint Sit-Down Strike, 1936-37

Source: jalopnik.com

Yet, GM and law enforcement were determined to retake the factories in Flint and crush the strike.

Subsequently, a ferocious battle between strikers and Flint policemen—dubbed ‘The Battle of the Running Bulls”—climaxed when officers wheeled and fired into the crowd of unionists. Fourteen strikers and two picketers were wounded by the spray of gunfire. That no one died is something of a miracle.

Battle of the Running Bulls, Flint Sit-Down Strike, 1937

Photo source: retronewser.com

“This was a war zone,” New Republic journalist Mary Heaton Vorse reported.

Michigan Governor Frank Murphy summoned the Michigan National Guard to the streets of Flint. From that time forward, the Guard effectively served as a buffer between the unionists and those who opposed them. Murphy was determined to keep the peace and remain neutral for the duration of the strike.

Michigan National Guardsmen, Sit-Down Strike, 1936-37

Photo source: History.com; Bettman Archive/Getty Images

Unionists forced GM’s bargaining hand when they occupied Chevrolet Four after staging a diversionary battle at Chevrolet Nine.

With Murphy serving as de facto mediator, the warring parties inked a one-page agreement which recognized the UAWA as the exclusive bargaining representative for GM employees.

Aftermath

“The Flint sit-down strike is the beginning of the United Auto Workers of America’s rise to become the nation’s preeminent labor union—the union that sets the standard for wages, benefits, and working conditions for industrial laborers,” McClelland asserts.

“The militancy that inspired the Flint sit-down strike was passed down to the next generation of Flint autoworkers, and to the generation after that,” McClelland writes. “The sons and grandsons of the sit-downers believed that their labor had built GM, and that the company owed them good wages and benefits in return.”

“Flint (once) boasted the highest median wage for workers under thirty-five in the country, thanks to union contracts that allowed new employees to start at the same wage as their more experienced line mates,” McClelland continues. “The city’s overall income was higher than San Francisco’s”

Historical voyeurism

McClelland’s Midnight tears back curtains and opens doors onto scenes of great consequence as when Frances Perkins, the first woman to occupy an Executive Branch cabinet position as Secretary of Labor (1933-45), berates GM CEO Alfred Sloan for his unwillingness to bargain with UAWA representatives (excerpted above).

Frances Perkins, former Secretary of Labor

Photo source: Frances Perkins Center

Thus, what distinguishes McClelland’s account of Flint’s sit-down strike from many other sit-down narratives is the intimacy of the experience. The author escorts the reader into an office on G Street in Washington DC for a meeting between auto executives and Perkins. Perkins has departed FDR’s first inauguration parade early for the meet up, only after whispering details of the clandestine meeting into the president’s ear.

At a small room in Flint’s Dresden Hotel, fly-on-the-wall readers will witness strike leaders hatch the plot to take over Chevrolet Four by using diversionary tactics at Chevrolet Nine.

During the violent takeover of Chevrolet Four, striker Gib Rose “grabs ahold of (his old foreman’s) belt and collar, marches him to the loading dock, and (safely) pushes him off…‘Now, go before you get hurt!’ Rose commands. ‘I’m your friend, dammit! Run!’”

A large cast of characters, well-known, and not so much

McClelland’s Midnight fleshes out familiar characters in government (Roosevelt and Murphy), labor (Lewis and the Reuther brothers), and industry (GM’s Sloan and William Knudsen). And the importance of Perkins cannot be overstated.

Frances Perkins, behind FDR

Source: Time Magazine

But lesser-knowns, like two locals, the Perkins brothers—Bill, 27, and Frank, 29—Fisher One workers from nearby small-town Columbiaville, fed up with their working conditions, stage an independent, unannounced, two-person sit-down weeks before the main event. They lose their jobs but are eventually rehired. More important, they plant seeds of revolt.

The reader will learn that Lawrence Fisher, one of Fisher Body’s founding brothers, doesn’t want the strikers expelled from the factories by violent means. “If the Fisher Brothers never make another nickel, we don’t want bloodshed in that plant,” Fisher told Murphy.

Wyndham Mortimer and Michigan Governor Frank Murphy shake hands after the signing of the contract to end the Flint sit-down strike, Detroit, Michigan; Feb. 11, 1937

Photo source: Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University

Michigan National Guard Captain Brice C. W. Custer, grand-nephew of the ill-starred general killed at Little Bighorn, arrives in Flint at the head of a 65-member howitzer company from Monroe, Mich.

A host of other unionists—Wyndham Mortimer, “Bud” Simons, Homer Martin, Bob Travis, Genora Dollinger, Kermit Johnson, Henry Kraus, Henry Clark, Prince Combs, Ed Kronk, Howard Foster, Bill Roy, Carl Bibber, Joe Sayen, Henry Lorenz, Roscoe Van Zandt, and others—find their way into McClelland’s narrative. As do those who oppose the union.

Ephemeral victory

“America’s greatest twentieth-century invention was not the airplane, nor the atomic bomb, nor the lunar lander,” McClelland concludes. “It was the middle class.” If so, the catalyst for that middle class unfolded right here in Flint from Dec. 30, 1936 to Feb. 11, 1937.

Labor unions and the middle class, however, are shrinking from the American scene. “Today, GM’s Flint-area workforce is down to 6,500—less than a tenth of what it was in the 1970s,” McClelland writes. “That’s consistent with the overall decline of GM’s hourly employment which has fallen from 511,00 to 50,000, as a result of automation and the loss of market share.”

The average CEO earned twenty times as much as his employees in 1950; that has ballooned to a factor of 300.

McClelland posits in the final pages of Midnight: “The shrinking of the middle class is not a failure of capitalism. It’s a failure of government. Capitalism has been doing exactly what it was designed to do: concentrating wealth in the ownership class, while providing the mass of workers with just enough wages to feed, house, and clothe themselves…and it can only be arrested by an activist government that chooses to step in as a referee—as Frank Murphy, Frances Perkins, and Franklin D. Roosevelt did in 1937.”

McClelland concludes, “The blueprint for better working conditions, and for a revival of the middle class is in this book.”

McClelland’s Midnight in Vehicle City, published by Beacon Press, is on sale beginning Feb. 2, 2021. http://www.beacon.org

EVM Staff Writer Harold C. Ford is the son of an auto mechanic and a lifelong Flintstone. He belonged to four unions during his years of full-time employment: Laborers’ Local 1075 (thrice); AFS-CME; UAW (thrice); BEA-MEA-NEA (30 years, 3 strikes).

* * * * *

A conversation with Edward McClelland about the book begins at 6 p.m., Feb. 2, 2021 at the website of Literati Bookstore in Ann Arbor. The event will be moderated by Anna Clark, most recently author of The Poisoned City, Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy, 2018, Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and Company.

https://www.literatibookstore.com/event/home-literati-edward-mcclelland-anna-clark

also, The Flint Public Library will host a book discussion of Ted McClelland’s book on Thursday, March 4, 2021 from 1 p.m. to 2 p.m in their Booked for Lunch via zoom series. Click here for the link to connect to the virtual book discussion.

Suggested links to other related EVM articles:

“I Love Flint” piece with some historical references: https://www.eastvillagemagazine.org/2019/02/14/i-love-flint-bakers-dozen-reasons-why-my-town-is-not-the-11th-worst-city-to-live-in/

“’Flint Town’ panel discussion:

Water Crisis Town Hall with comparison of water crisis to Sit-Down Strike

You must be logged in to post a comment.