By Tom Travis

Hostile Terrain 94 is an art exhibit on display at Flint Farmer’s Market until Nov. 27. Created by UCLA anthropologist Jason De Leon the exhibit aims to raise awareness about the realities of the U.S-Mexico border, focusing on the deaths that have been happening almost daily since 1994 as a direct result of the Border Patrol policy known as “Prevention Through Deterrence” (PTD), described in materials at the art exhibit.

The Hostile Terrain 94 art exhibit is on display at the Flint Farmer’s Market. The exhibit is displayed on a 16-foot board located on the first floor in the food court area near the large windows looking out on to First Street. (Photo by Tom Travis)

Public invited to “participate” in the Hostile Terrain 94 art exhibit

An online presentation of the art exhibit can be found at this link: www.hostile-terrain-flint.tk. It is described as “participatory” in that the public can touch and read the names on the exhibit. Also, volunteers can participate by hand-writing a toe-tag themselves with the information of the deceased person that will be placed on the display board.

Each manilla-colored toe-tag in the art exhibit has personal information about the person’s remains discovered at the border. (Photo by Tom Travis)

The public is invited to participate through the physical act of writing out the names and information for the dead invites participants to reflect, witness and stand in solidarity with those who have lost their lives in search of a better one. Several toe-tags on the display have QR codes that connect to online content regarding migrant issues along the southern U.S. border.

A QR-code on one of the toe-tags of unidentified remains. (Photo by Tom Travis)

UM-Flint Anthropology students and professors assist in Hostile Terrain 94 exhibit

UM-Flint Anthropology professor Daniel Birchok explains that the area of the U.S./Mexico border displayed in the exhibit is in the Sonoran Desert, in Arizona, south and south west of Phoenix and Tucson near the city of Nogales, Mexico.

The art exhibit is a series of red pins with a toe-tag hanging from each pin displayed on a 16-foot board with the cities of Phoenix, AZ and Tuscon, AZ on it as well as a thick black line representing the U.S./Mexico border.

The toe-tag has the name of the person along with the precise longitude and latitude where the remains of the deceased immigrant were found. Orange colored toe-tags mark unidentified remains and manila colored toe-tags mark an identified person’s remains.

There are over 3,200 toe-tags on the Hostile Terrain 94 art exhibit representing those remains of people who have died in this area since “roughly the mid-90s”, explained Birchok. The 3,200 number could easily be “doubled” because bodies decompose so quickly in the desert, according to Birchok in referencing the work of De Leon. De Leon does much of his anthropology work in this area of Arizona.

UM-Flint anthropology professor Daniel Birchok (right) and display volunteer and UM-Flint student and vice-president of the Anthropology Club, Brendon Nelson stand in front of the “Hostile Terrain 94” art exhibit. (Photo by Tom Travis)

Birchok explains that this art exhibit gives awareness to “failed” U.S. Immigration policy, explaining, “This becomes a matter of a U.S. federal policy question. Back in the mid-1990s border patrol began to emphasize fortifying the border in urban areas to push people from crossing the border in the desert in hopes that the hostile terrain would prevent people from crossing. Instead it resulted in all this death. The policy wasn’t successful,” explained Birchok.

UM-Flint Associate Anthropology Professor Jennifer Alvey added, “Border patrol policy increased surveillance in control of the border in urban areas to kind of thwart immigrants from trying to cross. But what happened was that [the immigrants] didn’t stop coming but they were forced into seemingly unpatrolled areas in this desert.

“Policy makers thought because of the hostile terrain it would make the immigrants not want to come. But instead immigrants crossed there in large numbers, as before, but they died because of the conditions.”

Alvey added, “Surveillance techniques have gotten more sophisticated which kind of intensifies people’s desire to travel through the desert rather than other areas. But because of U.S. policy immigrants are still being funneled through the desert.”

UM-Flint Associate Anthropology professor Jennifer Alvey. (Photo source: UM-Flint College of Arts and Sciences Facebook page.)

Both Birchok and Alvey commented that a vast majority of the 3,200 markers representing immigrant deaths that crossed this particular area of the border died from exposure to heat and cold. “This area has very “frigid temperatures at night.” Also some died because they had pre-existing conditions such as diabetes and they went into renal failure, Alvey added.

Birchok describes the exhibit as an example of “public anthropology.” “We often absolve ourselves of responsibility because people are dying in the desert and we think, “Oh that’s natural. That’s not our fault. But it’s actually, in part, [federal] policy. So again, anthropology lets us think about this arbitrary distinction between nature and the social so that’s how they are intertwined.”

Volunteers are working on the exhibit pinning the tags to the precise location where the remains were found. Each eight-and-a-half by eleven piece of paper posted on the 16 foot display board represents a quadrant of land noting the location of found remains.

Students and Professors volunteer to pin toe-tags onto the 16 foot art exhibit at Flint Farmer’s Market. (Photo by Tom Travis)

The volunteers transfer those locations on the paper to the display board with a red pin and toe-tag. Once a quadrant of land is fully marked the paper is removed and red pins and toe-tags remain creating the exhibit.

Anthropologist Jason De Leon has created the participatory art exhibit now displayed at Flint Farmer’s Market until Nov. 27, 2021. (Photo source: UCLA.edu website)

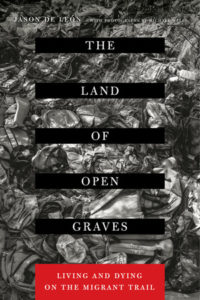

De Leon’s 2015 book, Land of Open Graves explains more fully the federal policies that contribute this type of migration and deaths in crossing the border, Birchok said. More information about Land of Open Graves can be found at the following link: www.jasonpatrickdeleon.com/land-of-open-graves.

Birchok asserted his hopes for this project saying, “That people are aware that this is happening and that it informs how we are thinking about immigration policies and how we treat immigrants. And also I think a big part of this is simply we often think of border crossings in the abstract or undocumented but we don’t really like think about their names or real people.

“This exhibit identifies real people who have died in the process of crossing the border. This exhibit allows us to remember these are real people, with real families and real concerns just trying to make a better life for themselves.”

Beverly Smith, who has been an archeologist and associate professor of anthropology at UM-Flint specializing in human remains analysis for over 30 years, worked along side student volunteers pinning red markers on the display board.

UM-Flint associate professor of Anthropology, Beverly Smith, stands in front of the Hostile Terrain 94 art exhibit in the Flint Farmer’s Market. Smith has taught at UM-Flint for more than 30 years. (Photo by Tom Travis)

Reflecting on De Leon’s public art exhibit Smith said, “Well I think it’s a wonderful application of anthropology and integrates both cultural anthropology and our interest in human migrations and the suffering of people in that and all the things we should pay attention to. It helps us to remember that it’s very important to identify remains of people who have been skeletonized which is an extraordinarily difficult process.

“I think that one of things that this exhibit does is that it brings together all the different forms of anthropology in a meaningful project like this.” Smith described the forms of anthropology as: archeology and biological-anthropology are two types of forensic work to identify remains. And then there’s cultural anthropology and linguistic anthropology those are the four types of anthropology and disciplines, explained Smith.

Smith’s most recent archeology project was when she directed an anthropological team on the Stone Street Project in the historic Carriage Town Neighborhood. A Native burial was accidentally discovered on the west side of Stone Street just south of University Ave. when former foundations of homes were unearthed to make way for new housing. The area is now fenced off and is deeded to the Saginaw Chippewa tribe.

More information can be found here:

Twitter @HostileTerrain

Instagram @HostileTerrain94

Facebook: www.facebook.com/hostileterrain94

Hashtags: #hostileterrain94 and #ht94

www.hostileterrain94.org

EVM Managing Editor Tom Travis can be reached at tomntravis@gmail.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.