By Jan Worth-Nelson

One Thursday in August, as Virginia Tech researcher Marc Edwards was presenting his most recent findings to the cameras and lights nearby, another less glamorous group of us — me a lone reporter in the third row — were sitting restlessly in a chemistry class at City Hall.

One Thursday in August, as Virginia Tech researcher Marc Edwards was presenting his most recent findings to the cameras and lights nearby, another less glamorous group of us — me a lone reporter in the third row — were sitting restlessly in a chemistry class at City Hall.

It was actually a meeting of the Flint Water Recovery Group, an ongoing consortium of social service agencies and residents closely following the water crisis. Every week this group convenes to share information, coordinate water supplies and other commodities, and ask questions of relevant outsiders.

This day’s “teachers” were Mark Durno, a supervisory engineer and Flint on-scene coordinator from the Environmental Protection Agency and George Krisztian, Flint action plan coordinator and laboratory director from the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality.

We didn’t exactly sign up for this class, but there we were that day, in the dim light under the dome.

The two men were, it seemed to me, exceptionally careful, straight-forward, and respectful, taking pains not to claim too much.

They were trying to explain to us how things are going. To do so, they presented a PowerPoint with charts. In a way, in such situations they are the ones being tested.

Mark Durno

“There’s no mistake, none of us with acronyms on our shirts are completely trusted,” Durno said. He was talking about the importance of Edwards, whose data provided not just a scientifically necessary objective third source of scrutiny, but a psychological one as well.

That day’s presentation was a continuation of a class we’ve all been in for more than two years. And I don’t mean just this stalwart group of about 80, from the Red Cross and United Way and Christ Enrichment Center and a dozen other agencies, but almost everybody in the city.

“I just wish I’d paid better attention in chemistry class,” Tony Lasher, executive director of the Red Cross and moderator of the FWRG meetings, says with a rueful smile at a recent meeting.

We’ve all been learning chemistry. Hundreds – thousands — of us have been turned by the reality of our crisis into mini-researchers. And some of us, it seems, have been conducting our own little independent studies.

All in the name of the water we drink.

Remember when none of us knew what TTHMs meant? Now we do, though maybe we can’t spell it – (total trihalomethanes) and why it matters. We can toss around terms like “sequential sampling,” “action levels of parts per billion,” “micrograms per deciliter” and “chemical parameters.”

And oh yeah, we can talk orthophosphates and chlorine like a bunch of high school geniuses on Quiz Bowl.

In my case, recently I looked at the periodic table of elements for the first time in about 50 years and spotted Pb – the chemical symbol for lead (in the carbon group, atomic number 82) also called plumbum. Funny word, one we could do without, that plum bum. And I remembered the word plumber – praise be to those who’ve helped us – comes from the Middle English for a person working with lead. Who knew?

George Krisztian

Durno and Krisztian said Flint has gone from being the “worst” to the “best monitored water system in the country.” Much of that data has come from Flint residents ourselves – as we’ve filled thousands of plastic bottles and turned them in for testing, as we’ve let numerous rounds of researchers into our homes, as we’ve talked to them over and over again.

We’ve learned how to understand and interpret their jargon. And we’ve become scientists on our own.

It appears, Durno and Krisztian said, many people are conducting their own mini-studies when turning in water testing kits. When seeing two kits from the same address, from the same day and time – with differences in the results — lab workers concluded people were testing both their filtered and unfiltered water.

Flint residents’ curiosity and initiative, in other words, is extending beyond the formal protocols – maybe because there’s a lot at stake for us. Maybe we’re fascinated by the hope of seeing change in the making. Maybe we just don’t believe what we’re being told about our water and want to see for ourselves.

Almost everybody I know has followed their home testing results with intense interest – tracking their “parts per billion” in both lead and copper (Mine: 2 ppb lead, 6 ppb copper – phew.)

Then there was the matter of the May “Flush for Flint” campaign, when we were instructed to run our taps five minutes a day.

Originally, Steve Branch, Mayor Weaver’s chief of staff, suggested to the Thursday group that the “Flush for Flint” campaign had done little good. I remember feeling chastised, as if I hadn’t done my part.

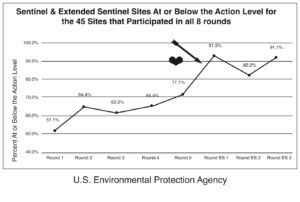

Image of the EPA chart I love, suggesting a possible correlation between the “Flush for Flint” program and improvements in residential lead levels. Arrow and heart added by EVM.

But over the next few weeks, Durno and Krisztian noticed something that told a different story. In their examination of results from their “Sentinel” and “Extended Sentinel” sites – two groups of homes in the city whose water has been intensely studied – in the month following “Flush for Flint” there was a positive jump – from 71 to 93 percent “at or below the action level” – that’s good news. It means many more homes, at least in their test group, had lower lead levels – levels below that scary 15 ppb the EPA has suggested is the point at which the water becomes dangerous. They didn’t have proof to explain the change, and being scientists, they understood that correlation doesn’t necessarily mean causation. However, using “back of the envelope calculations,” as Durno put it, they could see that if enough people had flushed, it could have created that beautiful spike.

“My opinion is that Flush for Flint did have an impact,” Durno said. “We surveyed our residents and 70 percent participated.” The researchers had determined that a 6 per cent increase in usage would be enough to effect change – and “we got it,” he said.

To understand the evidence for what we did, we had to read a chart. I love that chart. After all the emotion and politics, the chart tells a story of one thing, of many, the community did together for our recovery.

Sitting there under the dome that day, trying to figure out the “x” and “y” axes, I kept thinking about LeeAnne Walters. In a November 2015 interview with East Village Magazine, Walters, the now-celebrated and powerful water activist who graduated from Kearsley High School, said she had learned a lot of chemistry during the water crisis.

At the early water meetings, she said, officials from the MDEQ and emergency manager Jerry Ambrose “called me a liar and they called me stupid.

“I am neither of those things,” Walter told our reporter, Ashley O’Brien, “so I decided to go with the science. You can’t argue with science.”

If there is ever a final exam, or even a midterm in this chemistry class, we don’t know when it will be, and we don’t know when the semester will be over. In fact, it’s our teachers who are on the line.

The final exam of the chemistry class we’re all in will be the kind I used to hate – the kind you can’t write your way out of, the kind where you have to show what you know. In this case, the test is to apply all the theories and hypotheses and methods.

The final exam for these teachers – Durno and Krisztian and Mayor Weaver and Gov. Snyder and all the others, will be clean drinking water.

And in the meantime, this town so often seen as a swamp of trouble, sometimes characterized with the condescension of privileged outsiders – oh, those poor, poor souls in Flint — that town of beleaguered dim bulbs has turned into a think tank.

We are not stupid. Over the past two years, the people of Flint have learned to pay attention in class. It’s the most important class: the class of our own experience.

We’ve found out sometimes science actually helps you understand how to live.

We’ve found out sometimes you go to class because it’s a way to save your own life – and stop the fakers who are telling you lies.

EVM Editor Jan Worth-Nelson can be reached at janworth1118@gmail.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.