By Paul Rozycki

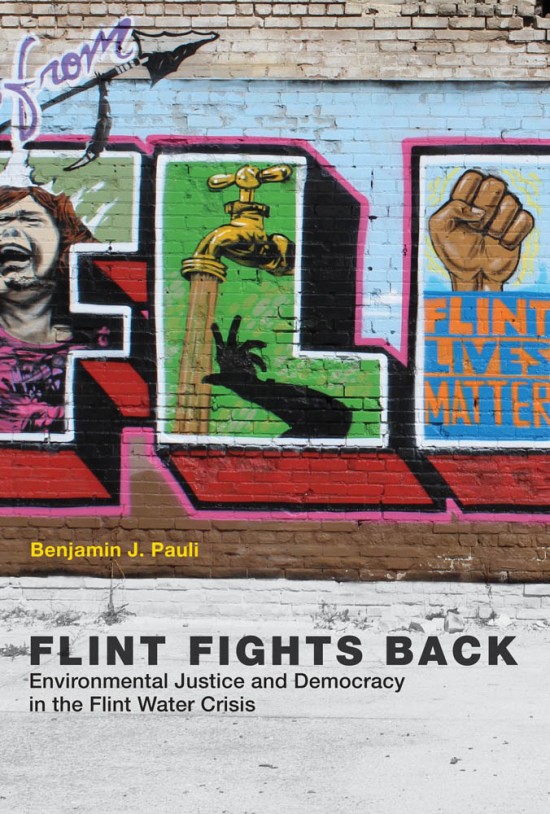

At the recent launch of his new book Flint Fights Back: Environmental Justice and Democracy in the Flint Water Crisis, activist and Kettering University Professor Benjamin Pauli contended that the loss of democracy and the struggle of Flint activists to reclaim and ferociously exercise it, is at the heart of the Flint crisis.

“We didn’t have a say about our water source,” he said, and that led to many of the problems that ensued. Yet, he asserted the water crisis, and the response of activists to it, is also “a triumph of democracy, as the people took control of their lives.”

Pauli, who arrived in Flint in mid-2015, is an assistant professor of social sciences at Kettering. Starting in January, 2016, he became actively involved in the activist community, sometimes having to toe a challenging line.

Benjamin Pauli at the Totem book launch (Photo by Paul Rozycki)

In the preface to the book he said, “By joining up with both the water activists and the scientists on the front lines in Flint…I gained what I believe to be a unique vantage point on the crisis, conducive to capturing its complex and multifaceted character. I was an activist and also a researcher; a comrade in struggle but also a newcomer to the community and the movement; a resident but also a member of a privileged demographic, whose perspective did not always align– for better or worse—with that of the other residents and activists.”

Pauli’s book launch was hosted by Totem Books, 620 W. Court St. on May 16, with a discussion moderated by East Village Magazine Editor Jan Worth-Nelson. More than two dozen attended the discussion that highlighted the role of the citizen activists in the crisis. In addition to Pauli’s family, friends and colleagues, the group included some of Flint’s most vocal and best known water activists.

In the discussion with Worth-Nelson and the group, Pauli touched on several key themes of his book. While it is about the water crisis, he said it’s also about much more.

Most significantly, Pauli argues, the water crisis developed from a failure of democracy. The emergency manager system, put in place to oversee Flint financial problems starting in 2011, denied local residents the ability to govern themselves. That lack of democratic control led to decisions over which Flint residents had no voice–most consequentially, the move to the Flint River, the lack of corrosion control, and a series of bureaucratic bungling very familiar to Flint residents as the crisis enters its fifth year.

Most significantly, Pauli argues, the water crisis developed from a failure of democracy. The emergency manager system, put in place to oversee Flint financial problems starting in 2011, denied local residents the ability to govern themselves. That lack of democratic control led to decisions over which Flint residents had no voice–most consequentially, the move to the Flint River, the lack of corrosion control, and a series of bureaucratic bungling very familiar to Flint residents as the crisis enters its fifth year.

Yet while the lack of democracy was complicit in the crisis, the response of the public and the water activists also revealed the ability of an activated public to respond effectively to a crisis. As Pauli put it, “Every time the people challenge authority is a part of democracy.”

Pauli also highlighted the importance of race and class in the story of Flint’s water crisis.

He spoke of the decades-long history of racism and racial conflict in the city. But he also argued the conflict in Flint wasn’t only about race—it was also about class. He said the activists were wise to focus on both race and class, as they attempted to unite diverse groups within the city. The city not only has a long history of racial division, he noted, but has also gone from one of the wealthier cities in the nation to one of the poorest.

A third theme of the discussion was the importance of knowledge and science, and the way so many of the activists were discounted by the experts, because they didn’t have degrees after their names, and didn’t behave in the “correct” way.

According to Pauli, this also was part of the power dynamics that led to the crisis. Many of those with the professional backgrounds found it all too easy to dismiss the observations, complaints and experiences of those who weren’t experts.

In the end, many of the “non-experts” became well versed in the science and technology of water, while still struggling to be taken seriously. He said the water crisis became an example of how the professional experts and “the people,” via the activists, finally came together.

Activist Claire McClinton makes a point as activist attorney Alec Gibbs looks on (Photo by Paul Rozycki)

It was “not a philosophical theory, but an applied one,” he said. “We need to get past the stereotypes of activists, to understand how activism develops,” and learn that there is more than a “kernel of truth in the activists’ message.”

According to Pauli, governmental transparency is critical, adding that where there is no transparency, the public is likely to suffer. The water crisis, he said, is only one major example of that.

Yet, as Worth-Nelson said, the book is “not a love letter to activists.” She said it’s an honest look at both the ways in which water activists worked together, and their conflicts. Pauli said he wants to make it clear that “democracy is messy,” and he doesn’t want to romanticize the role of activists. They have made mistakes and they need to own up to them and correct them when necessary, he said.

St. Paul’s Episcopal pastor Dan Scheid comments (Photo by Paul Rozycki)

In the discussion that followed, many around the circle still expressed anger at the system that motivated them to become activists in the first place. Speakers questioned who really benefited from the emergency manager system, and what groups came out on top as a result. Several suggested that local foundations and downtown development groups were the main beneficiaries, not “the people.”

Radio talk show host Tom Sumner suggested the water crisis was “the canary in the coal mine” and that many other cities will face the same crisis. He asserted not just the infrastructure of Flint’s water system but also the infrastructure of democracy itself was really at risk–that the crisis was a fundamental failure of democracy itself, and that the emergency manager law was merely a stopgap measure.

Participants included Laura Mebert, Vicki Marx, Melissa Mays, Caleb Mays, Laura Sullivan, and Tony Palladeno, with author Ben Pauli and moderator Jan Worth-Nelson (Photo by Paul Rozycki)

Melissa Mays, an avid activist since the beginning and plaintiff with the Concerned Pastors for Social Action in a landmark lawsuit against the state, said the community needs to “see a victory” and that while “we are still drowning” in the water crisis, “we are solving some of our own problems.” Because of the activists, she said , “people are paying attention” beyond the borders of Flint.

Tony Palladeno, often one of the most vocal water activists, said “each of us has this disease in us, one way or the other,” as he spoke of his own health problems, and suggested the effects of the water crisis will be with Flint residents the rest of their lives.

Some spoke of continuing frustration with bad water, ongoing high water bills and other problems connected to a city continuing to face multiple challenges. Others praised the activists for “breaking the media blackout” and “putting clean water on the agenda.”

The book has been published by The MIT Press.

EVM political commentator and staff writer Paul Rozycki can be reached at paul.rozycki@mcc.edu.

Banner Photo: Laura Mebert, Vicki Marx, Melissa Mays, Caleb Mays, Laura Sullivan, Tony Palladeno, Ben Pauli, Jan Worth-Nelson (Photo by Paul Rozycki)

You must be logged in to post a comment.