By Harold C. Ford

By Harold C. Ford

“Education is the great equalizer…You can never bring families to Flint unless we improve the schools.” …Dana Dyson, Flint resident, Flint Board of Education meeting, Jan. 23, 2020

After seven meetings of its board of education in the first three weeks of calendar year 2020, Flint Community Schools (FCS) face an existential challenge probably unlike anything since the opening of Flint High School at S. Saginaw and Third Street in September of 1875, 145 years ago.

At its most recent meeting on Jan. 23, the Flint school board allocated $20,000 for a voter education campaign in hopes of passing a March 10 millage proposal that would more quickly pay off FCS’s massive debt. Yet, administration and board members are deeply divided about the details of proposed deficit elimination plans—including consolidation of schools—designed to reduce that debt.

The deep divisions are along geographic and racial lines as various school communities—notably those at Eisenhower, Pierce, Brownell, and Holmes—have packed board meetings in December and January imploring FCS board members to keep their schools open. To do otherwise, the schools’ advocates say, would lead to the further abandonment of Flint’s public schools by its students and parents.

The FCS administration and board of education have postponed a Jan. 30 meeting at which they planned to announce decisions on the Enhanced Deficit Elimination Plan (EDEP) and decisions about proposed building consolidations. No new date has been announced.

Daunting challenges:

FCS leaders face daunting challenges in 2020 that include:

- Convincing Flint voters to pass a 4.0-millage proposal headed to the March 10 ballot that would more quickly pay off the massive debt accumulated by FCS;

- Finding agreement on and implementing a deficit elimination plan that may include a plan for consolidation of buildings;

- Adopting a strategy to rid the district of at least 22 buildings already closed and 16 vacant properties;

- Continuing loss of student population—now reported to be 3,800, making FCS the 5th largest school system in Genesee County behind Grand Blanc, Davison, Carman-Ainsworth, and Flushing—and resultant loss of state financial aid;

- The departure of 78 educators in 2019 taking with them 1,014 years of experience in Flint schools;

- The staffing of several vacant classrooms with paraprofessionals and guest teachers still seeking certification;

- Continuing parent and staff reports of building climate challenges, both social and physical, especially at Flint Junior High in the Northwestern building;

- Two lawsuits by the American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan, one that challenges FCS disciplinary procedures, and another that seeks additional disability services for Flint children exposed to lead during the water crisis;

- Meeting the requirements of a three-year (2018-19 to 2020-21) partnership plan imposed by the State of Michigan to improve test scores by 10 percent, reduce suspensions by 10 percent, and increase attendance to 90 percent.

A district deep in debt:

“The issue at hand is this,” said Derrick Lopez, FCS superintendent. “The district has a budget deficit of $5.7 million a year resulting from a legacy debt (loan) of $2.1 million a year and an additional $3.6 million annually in special education services…Unfortunately, there is no silver bullet to repair this massive deficit…The cavalry isn’t coming.”

Among the plethora of newly-posted documents (about 50 in all) at the FCS website under “Superintendent’s Office” is the “2019-20 Approved Budget” which shows the following:

- Beginning Fund Balance: -$3,349,028

- Total Revenue: $67,913,616

- Total Expenditure: $70,833,059

- Ending Fund Balance: -$6,268,471

Other financial data now found at the website:

- Instruction expenditure (teachers): $30,852,366

- Support Services (paraprofessionals, administration, maintenance, transportation, etc.): $36,090,179

- Projected annual deficit in 2026-27: -$25,952,246

- Projected annual surplus in 2035-36: $744,444

Expenditure cut assumptions:

Financial data showing some projected cuts, or “Expenditure Cut Assumptions”, by fiscal year 2021 that have generated little public controversy include:

- Middle Cities Liabilities Insurance: from $1,288,620 to $788,620, a cut of $500,000 or 38.8%;

- Transportation: from $3,183,700 to $2,598,700, a cut of $58,500 or 18.3%;

- Custodial/Maintenance/Security: from $2,086,000 to $1,397,560, a cut of $688,440 or 33%;

- Legal and Audit Fees (likely, in whole or part, the Grand Blanc-based Williams Firm, P.C.): from $857,028 to $600,000, a cut of $257,028 or 29.9%;

- Rehmann Services (a Troy, Michigan-based public accounting firm): from $250,000 to $120,000, a cut of $130,000 or 52%;

- Workman’s Comp/Incentive Bonus Reduction: from $748,500 to $200,000, a cut of $548,500 or 73.28%.

- School Administration: from $2,055,970 to $1,143,970, a cut of $912,000 or 44.36% (includes reduction of seven administrators and four secretaries).

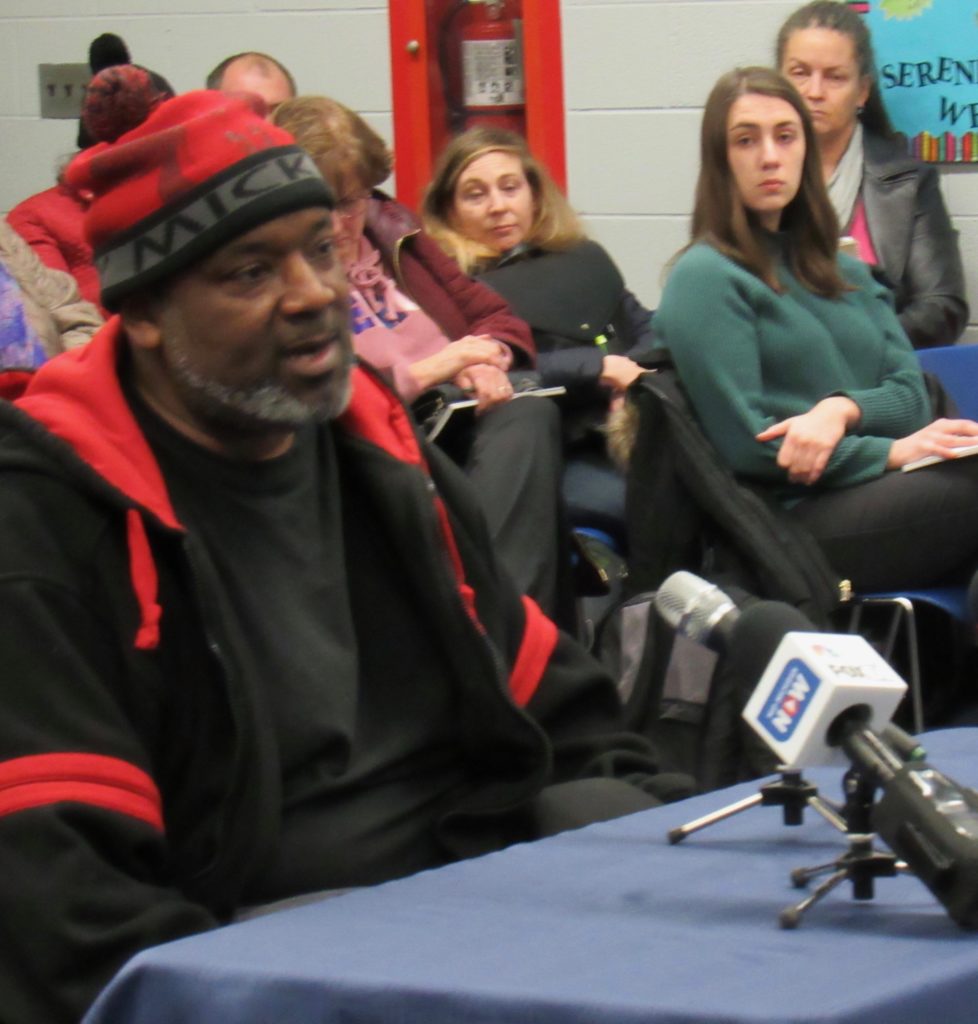

Part of the crowd of residents concerned about potential school closures at a Flint Community Schools board meeting (Photo by Harold C. Ford).

Building consolidation options:

Nothing, however, has generated more community interest and controversy than consolidation options floated to the public that include, or not, the following buildings:

- Flint Junior High School (grades 7-8), located in the former Northwestern High School building at G-2138 W. Carpenter Rd. (referred to as NW for purposes of this article, located on Flint’s north end);

- Southwestern Classical Academy (grades 9-12), 1420 W. Twelfth St. (SW, located on the south end);

- Accelerated Learning Academy (grades 7-12), 1602 S. Averill Ave. (ALA, located in the former Scott building, near southeast side);

- Brownell STEM Academy (grades K-2), 6302 Oxley Dr. (northwest side, next to Holmes);

- Doyle/Ryder Elementary (grades K-6), 1040 N. Saginaw St. (D/R, near central city);

- Durant-Tuuri-Mott Elementary (grades K-6), 1518 University Ave. (DTM, near central city);

- Eisenhower Elementary (grades K-6), 1235 Pershing St. (south side);

- Holmes STEM Academy (grades 3-6), 6602 Oxley Dr. (northwest side, next to Brownell);

- Neithercut Elementary School (grades K-6), 2010 Crestbrook Ln. (south side);

- Pierce Elementary School (grades K-6), 1101 W. Vernon Dr. (near east side);

- Potter Elementary School (grades K-6), 2500 N. Averill Ave. (east side).

The five consolidation options offered to the Flint Board of Education, simplified, include the following:

- Option 1: ALA students at Scott to SW; Eisenhower closed, students moved to DTM and Neithercut; Flint JH students to Holmes; Holmes students to Brownell; Pierce closed, students moved to D/R and Potter; projected budget surplus of $2,117,263/year.

- Option 2: ALA students at Scott to SW; Eisenhower no action; Flint JH students to Holmes; Holmes students to Brownell; Pierce no action; projected budget deficit of $887,370/year.

- Option 3: ALA students at Scott to SW; Eisenhower no action; Flint JH no action; Brownell students to Holmes; Pierce no action; projected budget deficit of $1,357,610/year.

- Option 4: ALA students at Scott to SW; Eisenhower no action; Flint JH students to Scott with addition of modular units priced at $160,000 to $310,000 each; Brownell students to Holmes; Pierce no action; projected budget deficit of $1,400,523/year.

- Option 5: ALA students at Scott no action; Eisenhower no action; Flint JH no action; Brownell students to Holmes; Pierce no action; projected budget deficit of $1,767,263/year.

Further, Lopez reported that the Administration Building at 923 E. Kearsley St., a frequent target of board members who urge its sale, has been appraised at $1.65 million. However, the cost of removing and relocating the infrastructure with the building would cost from $1 million to $2 million.

“Low hanging fruit”:

Lopez described the options for building consolidation as the most reachable goals to trim the massive FCS debt. “The low-hanging fruit in this plan is the underutilization of space we use in the district and making sure that we are utilizing it most efficiently,” he said.

“We don’t like closing buildings at all,” he said. “But I tell you, that is one of the things we have to consider.”

As an example, Lopez cited the Northwestern building which has seating capacity for 1551 students but currently houses only 400 junior high students. He said that cleaning and electricity for the building alone respectively cost FCS $141,500 and $328,000 annually.

Board opposition to building consolidation:

No matter the numbers or consequences, a majority of the seven members of the Flint board have expressed their opposition, in one way or another, to the consolidation of buildings:

- Casey Lester, president: “I don’t think anybody here would vote to close Pierce.”

- Diana Wright, vice president: “With my one vote I will not vote to close another school.”

- Betty Ramsdell, secretary: “I can’t vote to close any schools either.”

- Vera Perry, trustee: “I’m having a hard time with the closing of schools.”

- Blake Strozier, trustee: “In my heart and in my mind…I cannot support this plan as it is.”

- Danielle Green, treasurer: “A vote to close Pierce is not happening for me.”

“To not make a decision about one school being closed, you are now saying that instead of putting the money in the pocket of a teacher,” argued Lopez, “it’s OK to put money into a space instead of into our teachers’ pockets…The team we have assembled here has put us in a really fiscally responsible space.”

Flint Community School Board hears from resident and attorney Alec Gibbs (Photo by Harold C. Ford)

“A space of self-determination”:

“We are in a space of self-determination right now,” advised Lopez. “People are looking to see if we are willing to make decisions that are fiscally responsible.”

The “people” referenced by Lopez are likely State of Michigan officials at the Departments of Treasury and Education. Lopez read aloud a Dec. 13, 2019 letter from the Department of Treasury (now posted at the FCS website) which states, in part:

“…the State Treasurer determined that the (Flint) District is subject to rapidly deteriorating financial circumstances, persistently declining enrollment, and other indicators of financial stress likely to result in recurring deficits…This letter of approval shall be invalidated if there is a failure to meet the reduction targets identified in the EDEP.”

The legal basis for Treasury oversight and corrective actions is found in state law, specifically MCL 380.12 which, in part, speaks to “Loss of organization and dissolution of school district.”

Anyone who doubts the existential consequences for a school district of declining enrollment and fiscal challenges need only be reminded of three Michigan school districts that no longer exist: Saginaw Buena Vista (2013 closure); Inkster (2013); and Albion (2013-2016).

Passionate pleas by the Pierce and Brownell-Holmes communities:

Facing possible closures and consolidation, members of the educational communities at Pierce Elementary and the Brownell/Holmes Elementary Schools made passionate pleas to FCS officials at the January meetings to keep their schools open.

Pierce Elementary:

College Cultural Neighborhood resident Tyler Bailey: “It will lower our property values” (Photo by Harold C. Ford)

- Alec Gibbs, resident and parent, touted the highest test scores, lowest suspension rate, highest attendance rate, and a mentoring program as sufficient reasons for not shuttering Pierce. “It’s going to result in Flint kids in Pierce School leaving Flint.”

- Tyler Bailey, resident and former Pierce student: “Removing the last school in our area is just going to lower our property values.”

- Kristen Nix, resident and gardening project advocate: “Why would I pay into a millage and property taxes when you’re pulling the rug out from under these kids. We love our kids.”

- Jeanmarie Miller: “Any kind of plan that puts forth closing the highest performing schools makes no sense to me.”

- Maurice Davis, City of Flint councilperson: “You have a community that’s still intact. I highly advise this body to try to keep it intact.”

- Rebecca Pettengill, resident: This would really throw us under the bus.”

- John Topping, resident and attorney: “Closing schools decreases the quality, not only of the school system, but the quality of the community.”

- Elliott Milligan, resident and foster parent: “Pierce is a very welcoming school.”

Pierce Elementary supporter Elliot Milligan: “Pierce is a welcoming school” (Photo by Harold C. Ford)

Brownell and Holmes Elementary Schools:

- Jeanette Edwards, school volunteer, Brownell-Holmes Neighborhood Association president: “Why close our schools? It hurts my heart that our kids have to steady be changing.”

- Eric Mays, parent, resident, son of city councilperson: “It’s going to make it harder on these kids to have to be merged into this small school with all these other bigger kids.”

- Eric Mays, city councilperson, grandparent: “We don’t want overcrowding. We want space for support staff.”

- Forleasadon Harper, parent: “When do our kids become stable and secure in their education so that they can grow and blossom. We are the hope of the slave. We gotta’ want better for our kids.”

- Kim Probst, teacher: “I am a proud teacher at Brownell. I chose Flint. Do no more harm.”

- Amy Warren, teacher: “We’re the only K-2 building in the city of Flint…That’s a specialty; that’s a jewel…We can focus on what our boys and girls need so that they’re ready to transition.”

- Anita Wilkerson, retired teacher: “Brownell staff is wonderful. The parents are wonderful. If you do not support Brownell as it is, we’re going to lose more kids.”

- Dione Freeman, former substitute teacher: “The children are live human beings who have hearts and souls and need to have additional support besides just being numbers on papers.”

- Blake Strozier, FCS board trustee: “Every time we close a building, we lose students and, in some cases, we destroy an entire community. Flint cannot afford to have any more neighborhoods destroyed because of the lack of educational opportunities.”

- Diana Wright, FCS board vice president: “Our kids left when they closed those schools. I want all the kids at Westwood Heights to come back.”

- Vera Perry, FCS board trustee: “The kids are going to leave. I’m tired of seeing my parents and my babies walk.”

(Note: EVM reported in November about members of the Eisenhower Elementary community lobbying the FCS board to remain open.)

“Polarization of our community”:

“With these school closures, we’re just promoting…polarization of our community,” observed Desiree Duell, artist-activist and Flint Central graduate. Tensions around polarization and other issues were obvious during the January meetings as the FCS board and administration wrestled with tough decisions.

“There’s no transparency”:

Prior to the recent posting of some 50 deficit reduction documents, several residents complained to FCS officials about their lack of communication:

- Dana Dyson: “There’s no transparency. I could not find any documents pertaining to tonight’s planning meeting…I don’t understand why the board is keeping this information in secrecy.”

- John Topping: “The first word on my list is transparency…Show us what’s going to happen to the millage money…We don’t trust people who hide things.”

- Maggie Wright: “I found out about this meeting…one day before. Transparency, as a community we need this.”

- Claudia Perkins-Milton: “Itemize this stuff and let us know what the real deal is and where everything is going.”

- Arthur Woodson: “We, the public, are the last to know what is really going on. And then when we do find out, all hell breaks loose.”

The legacy of segregation:

In his 2015 work, Demolition Means Progress, author Andrew Highsmith wrote: “…a potent combination of private discrimination, federal housing and development initiatives, corporate practices, and municipal public policies converged to make Flint…the third most segregated city in the nation (by the 1930s).” That segregation was reflected in its public schools.

The impact of segregation on Flint’s schoolchildren, especially its children of color, could be destructive. Wesley King, for example, was one of 11 black students at Homedale Elementary in 1959 which enrolled 830 students. “After receiving complaints from white parents,” writes Highsmith, “King’s teacher decided to place (King’s) desk inside a coat closet.”

Informed by that history of their hometown, African American school officials often loathe decisions that deplete educational resources in their community. Thus, proposals to consolidate or close predominantly black schools on Flint’s north end have inspired passionate responses.

“We’ve killed the North End,” said Perry. “We have moved those babies and families around so much…We’re taking care of other areas, but we haven’t taken care of that north end.”

“How much more do we have to sacrifice before we completely leave the north end of Flint?” Strozier asked.

“Students on the North End have gotten a raw deal,” Wright added.

“Education wasteland”:

However well intentioned, Lester’s reference to the North End as an “education wasteland” during an emotionally-charged discussion was not well received by many at the board’s meeting on Jan. 23.

“That was not nice for you to say that,” responded Perry immediately.

“It’s gangsterous that, in the black community, you’re not sensitive to the black community,” charged A.C. Dumas, vice president of the NAACP Flint Branch.

Supt hot seat:

Community activist Arthur Woodson, a frequent visitor to FCS board meetings, bluntly challenged Lopez, Flint’s superintendent for the past 16 months. “You’re going to have to start working with the public, Dr. Lopez,” said Woodson. “They’re sayin’ it’s hard to work with you.”

Dumas went further. “I know, Dr. Lopez, you really don’t want to be here because you put in applications everywhere else,” he said. “You don’t want to be here. Your heart’s not here.”

It was reported by East Village Magazine in Nov. 2019 that Lopez was one of seven candidates who interviewed for the superintendent’s position at Farmington Public Schools. His appointment as Flint’s superintendent in Aug. 2018 was his seventh position in 15 years from 2003 to 2018.

Board members spar:

A heated exchange between board members Perry and Ramsdell flared briefly during discussion of consolidation options. “Mrs. Ramsdell, you can blow all you want,” Perry began. “The eyes you rollin’ and everything…I do have a right to say what I need to say because I live on the north side.”

“Don’t accuse me of that,” Ramsdell replied. “It’s not fair.” Ramsdell later apologized for her “outburst.”

“Decision-making phase”:

“Those who sit on the board, including the current superintendent, did not create these problems,” reasoned Dyson, a frequent attendee at FCS board meetings. “These problems are indicative of changes in urban America: closing GM, crime, people leaving urban areas, water crises, deindustrialization.”

“I have appreciated your hosting these meetings for the community to come together to express their concerns,” Dyson continued. “But it doesn’t stop now. Now we’re going to be moving into a decision-making phase.”

Banner photo of audience for FCS board meeting, mostly Brownell and Holmes STEM Academies proponents (Photo by Harold C. Ford)

EVM Education Beat reporter Harold C. Ford can be reached at hcford1185@gmail.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.